By the People, for the People

“Mic check!” calls out a young man from the bottom of the stairs at the southeast corner of Zuccotti Park, or “Liberty Square,” as it’s been called by the fans and residents of Occupy Wall Street (OWS).

“Mic check!” comes the reply from more than 200 people gathered for a General Assembly meeting on a chilly Sunday night in November. The park will be completely cleared in a predawn raid in nine days, but on this night, sitting on the concrete and rock steps that resemble a miniature Roman amphitheater, people crowd together—college students, parents with children, thirtysomethings, couples, retirees, lifelong and seasoned protesters, and tourists. Standing in the back, watching warily, are lots and lots of New York City police officers.

The young man leading the call this night is Craig Stephens, twenty-four, of New York City. He begins the process of explaining what has become the life beat of the Occupy Wall Street movement: the General Assembly (GA). The New York City General Assembly is composed of dozens of working groups that organize and strategize to set the vision for OWS. Stephens tells the attendees what the agenda is and how everyone will communicate (hand signals to show happiness, displeasure, a need to ask a question, a desire to add clarification, and how to block a proposal).

The GA is open to anyone who wants to attend; there is no attendance taken, and first-timers are welcome and have an equal opportunity to speak up and participate.

Stephens is joined by a team of five other co-facilitators who each have specific functions to keep the GA organized and running smoothly. One of the co-facilitators shares announcement and host-like duties with Stephens, two others go out into the crowd to answer questions about the process when there is confusion, and the final two keep track of those who wish to speak during discussion times. All co-facilitators are volunteers who have been trained by and are members of the “facilitating” working group.

Another working group has put together the agenda from a list presented by still more working groups, including those for “winter is coming,” “demands,” “press,” “community outreach,” and many more.

The first agenda item is an emergency announcement: In order to get the group’s generators back, the occupiers must comply with fire safety concerns expressed by the city. This means despite the inherent free nature of the camp’s design, specific egresses need to be designated and tent placements adjusted accordingly. Stephens then asks for a “temperature check” of the crowd’s mood. Most in the crowd signal their agreement with hands and fingers pointed up and wiggling.

There are no microphones, no megaphones to amplify sound. So the occupiers use echo repetition to ensure that everyone can be heard—similar to when soldiers are marching and a commander calls out a phrase, which the soldiers then repeat. At Occupy events, a facilitator or another speaker starts with a “mic check” to get the group’s attention. The group yells it back. Then, using short phrases that the group can easily repeat, the speaker begins his or her message.

“Are you happy?” Stephens yells to the crowd after introducing the co-facilitators and explaining their roles. “ARE YOU HAPPY?” the crowd repeats. The call-and-response continues:

“With your co-facilitators—”

“WITH YOUR CO-FACILITATORS—”

“For tonight’s GA?”

“FOR TONIGHT’S GA?”

“Temperature check, please!” Stephens now calls. The crowd responds with a majority of hands and fingers pointing up, fingers wiggling.

The mic-check process, as it’s known in the Occupy movement, is more time-consuming than simply listening to someone with a microphone; however, it also requires that almost everyone attending participate in the speech in real time. Everyone has to repeat the words in order for everyone to hear what’s going on. That act of repeating what’s said keeps the crowd attentive and focused, and makes everyone part of the action—not just a witness.

The second agenda item is an emergency request for funds for Occupy Harlem. OWS has received thousands of dollars in donations and is now working to assist other Occupy groups with funding issues. For this request, the GA is told that some of the funds will be used to reimburse individual Occupy Harlem participants who paid out-of-pocket to get a new boiler installed in a building that would otherwise have been condemned. The rest of the funds are to pay for personal items and supplies for the occupiers who are staying in the building with residents who would have been kicked out. The facilitators ask for those who wish to comment on the proposal to “stack up.” Facilitators take names and add them to a list; names are called out in order and each person is given the opportunity to speak.

The process hits some snags. One person suggests Occupy Harlem hasn’t asked for enough funds and suggests they ask for more: from $2,500 to $3,000. With a slight laugh, Stephens thanks the speaker for her comment and adds, “but that would be a friendly amendment—not a question or concern about the proposal. We will address this suggestion after this comment period has ended.”

Others raise questions about how much money Occupy Wall Street has and want to know more about the process for giving the money to others. Again, Stephens thanks the speakers and reminds them that there are working groups they may join in order to get those concerns answered, but the issue right now is only about whether or not to give Occupy Harlem the funds they have asked for.

After about thirty minutes of discussion and the adoption of a couple of friendly amendments (including the one that raised the asking amount to $3,000), Stephens asks the group for a temperature check. Hands go up, fingers pointing skyward. Stephens asks if anyone wants to block the proposal. No one blocks—consensus is achieved and the proposal is approved.

The third agenda item is to discuss Occupy Wall Street’s first official demand. The demands working group has prepared a written statement with a “Proposed Jobs for All” demand, to include “a massive, democratically controlled public works and public service program, with direct government employment, to create 25 million new jobs.” The proposal includes how to pay for the new jobs (new taxes on the wealthy, on financial transactions, and on corporate profits, as well as ending foreign military actions). The demand includes mandates for expanding access to education, healthcare, housing, mass transit, and clean energy without regard to immigration status or criminal record.

The demands working group asks the GA to break up into smaller groups, each with a facilitator from their working group, and discuss the demand for about twenty minutes. After that, the GA will reassemble and facilitators will report briefly on each group’s thoughts.

This process goes off without a hitch: Folks stand up, move around, and cluster quickly. Each group acts as a miniature GA; ideas about the demand—pro and con—fly fast and furious. In one group, several attendees are quick to point out that ending all military operations overseas will be costly, take time, and creates a new unemployment problem among both members of the military and the companies and contractors who work with the military. Others suggest that the demand is too complicated and ask for suggestions to simplify it. One woman objects to making any demand at all—she tells the group that their presence and actions are enough to have changed the national conversation. Others disagree, but no one is completely happy with the proposed demand. The twenty minutes are up quickly and the GA comes back together. A quick count of the crowd indicates there are still well over 150 people participating and it’s almost 8:30 p.m.—ninety minutes after getting started and with temperatures in the low 40s.

Several other items come and go on the agenda—consensus is reached on all of them after discussion and friendly amendments.

The final agenda item receives overwhelming support from the GA—dealing with the surplus of items OWS received so generously from supporters all around the world after the October snowstorm. The representative of the supply working group explains that it is against OWS ideals to horde the supplies. “That’s the self-serving system,” claims the representative. “We want to avoid becoming like the old system.” Dozens of hands fly up, fingers wiggling—signaling great enthusiasm for the sentiment.

The representative proposes two methods: First, donate 15 percent of the surplus to community outreach programs in solidarity with the 15 percent of unemployed Americans, and second, encourage sharing and more interaction between Occupy efforts across the country by offering travel reimbursement to occupiers from other locations who visit OWS to receive items and goods and take them back. Both proposals achieve consensus from the General Assembly.

The GA that night took almost three hours. It required constant attention and participation from those attending to ensure people could hear what was happening and to ensure there was consensus for the proposals. Yet no one complained about the cold, the time, or the hiccups. At the end, Stephens thanked everyone for being there: “It was difficult, it was hard, but it was beautiful!”

This statement could easily be applied to the entire Occupy movement so far. Participants are weary and challenged, but burn with a collective purpose and the vitality that comes with working against injustice. Tim Weldon, an OWS working group leader profiled in the November 16 New York Times commented, “I’m not a nationalist, I’m not in that mold. … I’ve been critical of the United States. But for the first time in my adult life, I feel like there’s a part of America that I, as an American, can belong to.”

Certainly humanists can empathize with the feeling of not completely belonging in a country where so many people not only believe in God as creator, but look to him for answers. But OWS, and the Occupy movement in general, is a people’s movement. It’s a movement that is trying to take responsibility for changing an unjust social and economic system. In this sense what I saw at Zuccotti Park was decidedly humanistic—including the repeated theme that “we’re all in this together,” and the Occupy movement’s commitment to the common good, for everyone.

Before reaching Zuccotti Park, I wasn’t sure if I was going to see chaos masquerading as a social and economic movement or a well-intentioned effort that had denigrated into a morass of filth, violence, and rampant drug use.

I found neither. What I saw instead was a well-organized camp of dedicated individuals who welcomed everyone: the media, tourists, individual unaffiliated protestors, and even the police. I saw a young man standing atop a marble column reading from a book while holding a sign identifying the book as Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience, while another protestor sitting in a folding chair along the sidewalk held a sign that read: “Keep your coins, I want change.”

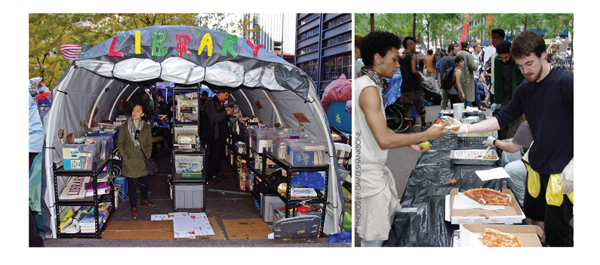

As I wandered through the crowded aisles of the camp, people were polite. There was no trash. And it smelled—well, it smelled like pizza (indeed, there was a pizza place across the street). I saw recycling and waste cans everywhere that were being emptied. The main organizational areas of the camp—the supply area, the kitchen, and the library—were neat and staffed by volunteers.

Throughout the day, small group discussions took place on a variety of topics: the Keystone XL Pipeline, starting a third political party, and woman and minorities in leadership. Each one was run like a mini GA, except without the mic-check. Everyone had the opportunity to talk. After each discussion, participants clustered around sharing names and email addresses—making connections and networking.

The people I talked to were as diverse as the United States itself: a self-proclaimed anarchist who works on Wall Street but was coming to OWS every night to pass out free literature; fresh college graduates who couldn’t find jobs or who were underemployed in North Dakota, Kansas, and elsewhere, and decided to join OWS; a retiree from northern New York who remembered the civil rights protests in the 1960s and believes just as strongly in the OWS movement; dozens of employed, tax-paying residents of New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey who had come for the weekend to participate, show support, and make noise about a system they believe isn’t working for a majority of Americans.

Now that the tents and facilities are being cleared from many Occupy sites around the country, the movement vows to shift to whatever form is necessary to endure. On November 17 protests in New York City and elsewhere marked the two-month anniversary of OWS. More protests are planned and the General Assemblies continue to do the work gathering information and involving intellectual, knowledgeable people to generate ideas that can eventually be translated into real demands and solutions. But just as systemic study takes time, so does systemic change.

Many people feel the current political and economic system is corrupt and rigged against them—no matter what they do. What I saw at OWS was a rejection of the status quo and a shaking off of the apathy that has seemed to plague a majority of Americans for years. Voting is the minimum that’s required of every citizen in a representative democracy—and because it takes time and effort to be involved in the political process, too many people have written it off as too broken to fix. Perhaps the OWS movement is the trigger Americans need to get active and make their elected officials responsible to them.

Whether OWS endures or not, let’s hope that the consciousness-raising it has achieved among all Americans—about the inequities of social services, of access to education, of the ability to earn a living wage—stay alive. These are humanistic values and affect us all. Perhaps it’s time for more humanists to become occupiers.

Amanda Knief is a firm believer in political activism as a means for social change. She lives and works in Washington, DC