If Voting Is So Important, Why Aren’t Fair, Open, Verifiable Elections Important?

It’s impossible in US society not to frequently encounter the demand to vote, no matter what, no matter for whom, as a basic civic duty. Voting is supremely important, we’re told, a right, a responsibility, a moral requirement, something people died for—and if you don’t use it (even if it’s useless) you will effectively be pissing on their graves. I saw a bumper sticker the other day that said: “If everyone would vote, it wouldn’t matter what the billionaires wanted.”

Let’s accept all of that at face value for the sake of argument. Let’s suppose it is our primary duty as members of society to vote. Personally, I always do, and it takes about five minutes out of my year. Sometimes I even promote candidates, and one might ask why that isn’t a supreme duty too, since it can impact how and whether numerous other people exercise their sacred duty to vote. Or we could extend that line of thinking further and ask why it isn’t the duty of each of us to work to change our culture so that only better candidates can get nominated, since that seems relevant to our duty to vote for some of those candidates. But I want to ask a different question at the moment.

Why does it seem to be of so little importance in US media and politics that US elections be brought up to, say, Bolivian standards of openness, fairness, participation, and verifiability? Is it our duty to keep up appearances despite living in an oligarchy? Or is it our duty to actually create some form of representative government that we can respectably mislabel a “democracy”?

At least part of the answer to why corporate media and elected officials care so little about reforming the US system of elections is that many in power don’t want more people voting or their votes being counted (more on this below). Another part of the answer is that everyone in power was put there through the current system. Another part of the answer is probably that once you’ve told people that all they can do is vote or be miserable, it’s hard to tell them all the things they’d need to do to reform the system of voting, and it’s not plausible to tell them that they can vote themselves the right to meaningful votes. Also, it’s a matter of basic national faith, even if nobody believes it, that the United States isn’t broken, especially in any ways that any other countries aren’t broken—and you can’t fix what’s not broken.

Yet another part of the answer is sheer inertia. The US electoral system is exactly like everything else in the United States in not having been reformed. This is a country that doesn’t use the metric system or end the semi-annual changing of everybody’s clocks, purely because that would amount to doing something, not because any powerful group opposes it. Yet, the US election system hasn’t just been staying the same. It’s been getting worse.

Hidden History

Thom Hartmann’s latest book is called The Hidden History of the War on Voting, and I like it despite despising the use of the word “war” for things that aren’t wars. Hartmann lays out a case that right-wing think tanks, media outlets, pundits, and politicians are working hard to make voting in the United States harder for some and easier for others. The case includes documentation of racism, disinformation campaigns, voter suppression, gerrymandering, unverifiable vote counting, and keeping inspiring candidates off the ballots through financial corruption, corporate media bias, and other means.

As with many things in US politics, this is a tale of Republican action and Democratic inaction. Republican secretaries of state have purged seventeen million people from the election rolls just between 2016 and 2018. After the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, fourteen GOP-controlled states restricted access to voting within a year, especially for communities of color, students, and retired people. North Carolina closed 158 polling places in the forty counties with the most African Americans. Nationwide, black and Hispanic voters typically wait much longer in line to vote. Former Indiana governor Mike Pence’s voter ID law reduced African-American voting by 11.5 percent in that state.

As president, Richard Nixon sabotaged peace talks. Ronald Reagan sabotaged hostage release plans. But by the year 2000 the Republican platform only stood a chance if voters were prevented from voting, so that’s where the emphasis went. Florida threw tens of thousands of African-American voters off the rolls, and still needed an assist from the US Supreme Court to steal the presidency for George W. Bush.

The trend continued. Between 2012 and 2016, Ohio purged over two million voters, over two-thirds of them in heavily African-American and Hispanic counties. In Wisconsin about seventeen thousand voters were turned away for lacking the type of ID required by a new ID law.

In numerous states, ID laws disproportionately prevent women from voting, as they’ve disproportionately changed their names upon marriage or divorce. In North Dakota, legislators passed a law requiring a street address to vote, precisely because Native Americans tended not to have street addresses.

Here are the nations that don’t explicitly establish a right to vote in their Constitutions: the United States, the United Kingdom, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Pakistan, and Singapore.

I should have just said “the world’s leading democracies,” right? Some US states are now making it a crime carrying jail time to make the slightest mistake on a voter registration form. Land of the free, indeed!

Don’t Mention It

To his credit, Hartmann mentions the unmentionable when it comes to US elections. The rest of the world treats—and the US prior to 2000 treated—exit polls as the gold standard by which to measure the credibility of election results. In the US post-2000, the official results are used to “adjust” exit polls to match their unbelievable results. Oddly, the adjustment is almost always in the direction of more votes for Republicans—hence the name “red shift.” In states without Republican secretaries of state, there is virtually no shift, and never has been.

If Hillary Clinton hadn’t had her heart set on blaming Russians, she might have blamed quite a few things for her 2016 defeat, including: an electoral college that gives a win to a loser; open intimidation and incitement of violence; stripping of voters from rolls; court battles to oppose the counting of votes; voter ID laws; a scarcity of polling places in poor neighborhoods; corporate media that promoted Donald Trump because it was good for ratings; her own godawful resume and campaign; and so on. Also this: the exit polls showed Clinton winning Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, but an inexplicable red shift altered those results.

I’m not sure why this is so unmentionable. Canada and Ireland tried electronic voting machines and rejected them because they were unverifiable. Even if you hold a firm belief that people who will go to enormous lengths to prevent the “wrong sort” from voting would never ever fail to count everyone’s votes once cast, what would be the harm in having paper ballots hand-counted at every polling place before every relevant witness, and re-counted if needed? What would it hurt? You couldn’t wait a day for the results after three years of offensive, infantilizing, degrading, distracting, and depressing electioneering? When Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, who oversaw his own election while serving as Georgia Secretary of State, was sued and immediately erased all the data on a server to prevent any vote counting, was that a sensible adult step to ward off any crazy speculation that might infect young people with habits of paranoia? Does it matter that in many cases the trust you’re placing is not in people at all, but in private corporations that now privately own US election data?

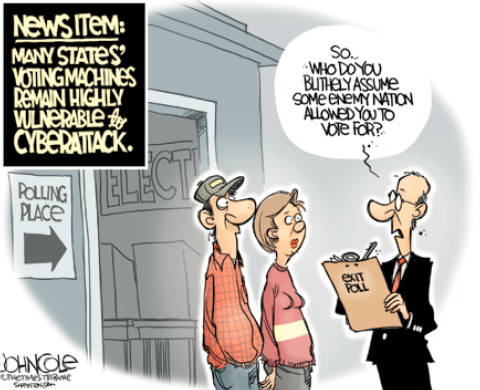

I thought that the fear of computer hacking by foreigners that has arisen in recent years was finally going to be enough to move people toward verifiable vote counting, but thus far it hasn’t.

What Do We Do?

The key answer is that we need non-voting activism of the sort that has always changed the world. Look at the packed streets in Lebanon, Puerto Rico, Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, Hong Kong, South Korea, and then look at the empty streets of Washington, DC. We need activism, disruptive and constructive, the 1,001 tools of nonviolent engagement and cultural change.

The key answer is that we need non-voting activism of the sort that has always changed the world. Look at the packed streets in Lebanon, Puerto Rico, Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, Hong Kong, South Korea, and then look at the empty streets of Washington, DC. We need activism, disruptive and constructive, the 1,001 tools of nonviolent engagement and cultural change.

But what do we need to demand? Hartmann points for part of the answer to a bill in Congress called HR1. The bill includes, among much else: automatic voter registration, same-day voter registration, bans on caging (sending postcards to voters and then removing them from the rolls if they don’t reply), restoration of voting rights to former prisoners, requirement of paper ballots (albeit without requiring hand counting), measures to prevent gerrymandering, and public disclosure of campaign “contributions.”

There are so many other things we can do to counteract this insidious affront to free, fair, and accessible elections. Three big steps in the right direction: abolish the treatment of spending money as free speech, ban private campaign funding, and create full public financing of elections. Other solutions that might be added to a to-do list include: abolish human rights for corporations; establish the personal right to vote; make election day a holiday; provide free air time in equal measure to candidates qualified by signature gathering; get rid of the electoral college; allow ranked choice voting; and allow statehood for Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico. For a nation whose political leaders and media do a lot of talking about democracy, it’s time that it walked the walk.