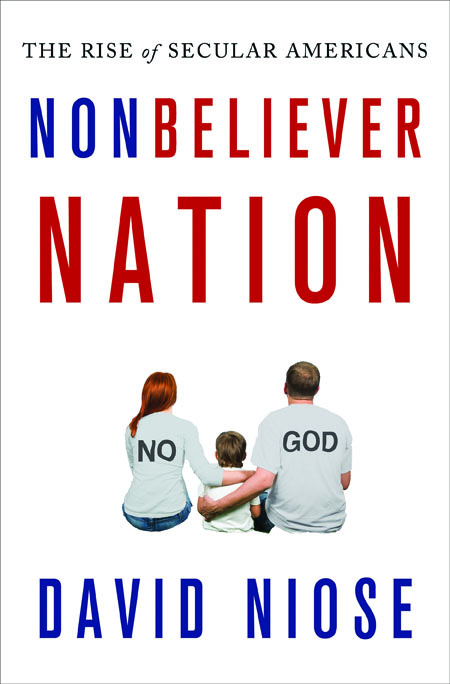

Nonbeliever Nation: The Rise of Secular Americans

“Religious freedom is a cherished American value,” writes David Niose in his new book, Nonbeliever Nation (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), “but religious predominance is not.” Published in July, the book takes the reader through a history of secularism in the United States and renders the powerful rise of the conservative religious right in sharp detail. But what makes the book groundbreaking is Niose’s survey of the growing number of Americans who call themselves secularists, humanists, atheists, freethinkers, and skeptics—in general, the nonbelievers who have been organizing and growing as a force to be reckoned with, namely by the religious right that continues to impose its dogmatic agenda upon the nation. An attorney who is also the president of the American Humanist Association and author of a humanist-themed blog for Psychology Today, Niose is perfectly poised to check and report on the pulse of the current secular zeitgeist. Richard Dawkins characterizes the book as “simultaneously disturbing and reassuring” and Michael Shermer calls it “The Feminist Mystique of this movement, destined to be a classic in freedom literature.”

The following three excerpts are from Chapter Seven of Nonbeliever Nation by David Niose. Copyright © 2012 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

The following three excerpts are from Chapter Seven of Nonbeliever Nation by David Niose. Copyright © 2012 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Reason for Hope and Hope for Reason

AS SECULAR AMERICANS have emerged over the last few years, one of the most fascinating and exciting areas within the movement has been the phenomenon of student activism. Religious skepticism on college campuses is nothing new, but what’s happening today is truly unprecedented. Across all lines of wealth, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation, students are standing up together to identify as personally secular.

The historical role of religion in higher learning is somewhat paradoxical. On one hand, by definition higher learning should be an exercise in skepticism—questioning facts, finding flaws in arguments, and developing work that can withstand intellectual scrutiny—so it should not be surprising that colleges and universities are havens for the critical analysis of religious claims and doctrines. Nevertheless, established churches have historically wielded enormous influence over social and political life in both Europe and America and, therefore, have often had close relationships with institutions of higher learning. Harvard, Yale, the College of William and Mary, and virtually all of the oldest colleges in America were mainly incubators for clergymen in their earliest years. When Connecticut legislators founded the college that would later become Yale in 1701, they declared that they were motivated by “Zeal for upholding & Propagating of the Christian Protestant Religion” to educate “a succession of Learned & Orthodox men” who through “the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for Publick employment both in Church & Civil State.” Thus, it is ironic that these bastions of intellectual pursuit, which would ultimately do more to chip away at the credibility of established religion than any other social institutions, were often established by men for whom the idea of separating God from academia would have been unthinkable.

With the Enlightenment already underway in Europe when religious men were founding the earliest American colleges, the relationship between religion and higher education was bound to eventually get tense. One obvious dilemma was that established religious institutions, which were by their nature conservative, inflexible, and reliant on ancient doctrine, needed educated, literate leadership to maintain power and legitimacy. This was not so problematic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when an advanced education did not necessarily conflict with religious authority. As the years progressed, however, Enlightenment ideas, industrialization and commercialization, the discoveries of Darwin, and other advances in knowledge made it increasingly likely that a college education would result in religious skepticism, not reinforcement. Over time, this resulted in the diminished role of religion in higher education, and as early as the nineteenth century we begin to see atheism and agnosticism as visible, sometimes even acceptable, schools of thought in establishment academia.

That trajectory continued into the twentieth century, resulting in skepticism being not the exception but the rule in many institutions of higher education. While schools of theology can still be found in many of the great educational institutions, theology as a discipline of study is often seen as a puzzling relic from a bygone era. Much more dominant are the schools of science, technology, medicine, law, business, and liberal arts, most of which, depending on the specific institution, are likely to be populated with instructors and students who, if asked, are skeptical or ambivalent about religion. Few courses of study will expose students to ideas that are particularly sympathetic toward traditional religion. This is in part because few of those doctrines withstand a search for empirical truth, and also because many courses of study, such as history, anthropology, and gender studies, expose students to ideas that may delegitimize religion and portray it in an unfavorable light. Students learn of historical and contemporary religious justifications for the mistreatment of women, the rejection of basic matters of scientific truth on religious grounds, atrocities attributable to religion, and convincing arguments that religion is a natural phenomenon and not the product of divine revelation, to name a few examples. Thus, for anyone alive today who has attended college, it is likely that notions of atheism, agnosticism, and general religious skepticism were a part of the college experience.

A Primary Secular Identity

Despite all this, even though atheists have been a fixture on America’s college campuses for decades, the situation today is unprecedented. Today’s secular students, unlike their parents and grandparents, see secular identity as a primary, important part of who they are. While there were atheists and agnostics all over college campuses in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, most nonreligious students in those days, if asked, would have first defined themselves as many things other than atheist or secular. They may have first seen themselves as liberal, conservative, socialist, libertarian, environmentalist, gay/lesbian, feminist, antiwar, no-nukes, or one of many other labels; in fact, their religious skepticism often would have been incidental and very low on any list of importance. Today, nonreligious students are increasingly seeing their personal secularity as a key aspect of their character and their approach to life, an identity that immediately conveys much about what they accept and reject.

Nothing better illustrates this point than the explosive growth of the Secular Student Alliance (SSA), the national umbrella organization for campus atheist and humanist groups. Founded in 2000, the SSA had less than fifty campus affiliates in early 2007, but by 2011 it had over 340. Currently, the SSA has affiliates from coast to coast and even throughout the Bible Belt. With groups such as the Penn State Atheist/Agnostic Association, Students for Freethought at Ohio State University, the Boise State Secular Student Alliance, and the University of Alabama Atheists and Agnostics, SSA affiliates demonstrate the national significance of atheist-humanist identity on college campuses today.

Nothing better illustrates this point than the explosive growth of the Secular Student Alliance (SSA), the national umbrella organization for campus atheist and humanist groups. Founded in 2000, the SSA had less than fifty campus affiliates in early 2007, but by 2011 it had over 340. Currently, the SSA has affiliates from coast to coast and even throughout the Bible Belt. With groups such as the Penn State Atheist/Agnostic Association, Students for Freethought at Ohio State University, the Boise State Secular Student Alliance, and the University of Alabama Atheists and Agnostics, SSA affiliates demonstrate the national significance of atheist-humanist identity on college campuses today.

“We’re witnessing a major shift in our society,” SSA spokesperson Jesse Galef told me. “More students are proudly calling themselves atheists, which inspires others to do the same. We used to go out and find them. Now they’re springing up everywhere and finding us, asking to join the movement.”

The reasons for this interest in secular identity are numerous. Often students point to the pervasive influence of conservative religion in their lives, which might explain why some of the strongest student groups can be found in areas known for religious conservatism. Just as reformed smokers are the strongest antismoking advocates, young people coming from fundamentalist families—having grown up with images of fire and brimstone, fear of damnation, and constant references to the Bible, God, Satan, good and evil—are often the most enthusiastic about their identity as secular individuals. With the growth of the religious right, the influence of conservative religion in many parts of the country is now quite overbearing, and young people who emerge from that environment as nonreligious understand the need for secular activism. Of course, even kids from moderately religious homes and nonreligious homes are well aware of the pervasive influence of the religious right in modern society. With mobilized religious conservatives so deeply entrenched, influential, and assertive that any young person interested in politics and social issues would have to be blind to overlook it, secular students from all kinds of family backgrounds are seeing the value of organized atheist-humanist groups as an affirmative rebuke of the religious right. Those interested in fighting for progress a generation ago may have targeted other political or social issues, but today’s students increasingly see secular identity and activism as vehicles for change.

Another factor is September 11, which has caused many to question the role of ancient, revelation-based religion in modern society. Christian fundamentalists at home were troublesome enough for many, but Islamic fundamentalist terrorism striking major American cities took concerns to a new level. Sam Harris pointed to the September 11 attacks as his motivation in writing The End of Faith, the first of the popular new atheist books, citing traditional religious faith as a most problematic phenomenon in the modern world. Many young people share his sentiments, and there can be little doubt that this at least partly explains the doubling of Americans identifying as nonreligious in recent years. “After the September 11 attacks, I began thinking that perhaps I should speak out against what I felt was a mindset that is not only wrong but dangerous,” said a former student named Ian, who was attending the University of Wisconsin when deeply religious terrorists took the lives of almost three thousand innocent victims on September 11, 2001. An openly secular life stance, for many young people, is a means of affirmatively taking a position in favor of reason and against ancient superstition.

What troubled many secular students after September 11 was the religious mindset not just of the terrorists but also of the political and military leaders fighting them. U.S. Army Lieutenant General William G. Boykin, for example, who served as deputy undersecretary of defense in the Bush administration until 2007, was vocal with his conservative Christian warrior rhetoric, casting the war on terror as a holy war with biblical implications. Repeatedly referring to America as a “Christian nation,” Boykin explained how he viewed one particular interaction with a reported Muslim jihadist: “I knew my God was bigger than his,” Boykin said. “I knew that my God was a real God and his was an idol.” America’s “spiritual enemy,” he is quoted as saying, “will only be defeated if we come against them in the name of Jesus.” Note that these are not the words of some anonymous soldier, but of a high-ranking officer and policy maker interacting with the secretary of defense and other officials in the highest circles of power. “Satan wants to destroy this nation,” Boykin warned, “and he wants to destroy us as a Christian army.” Telling crowds that he goes to prayer services five times a week, Boykin praised George W. Bush as a man who, though not elected by a majority of voters, “was appointed by God.”

It’s little wonder that nonbeliever students began to stand up as proudly secular in the face of such religious extremism emanating from the halls of their government. In generations past, the idea that elders held religious views that seemed outdated may have had little direct impact on the lives of students, but the increasing influence of the religious right calls attention to the error of conducting public policy from a biblical standpoint. To students who are nonbelievers, this simply highlights the importance of secular identity as a valuable, stabilizing influence.

Proud secular identity is seen as very problematic in some schools, particularly those that are connected to religious institutions. Catholic colleges such as the University of Notre Dame, for example, though usually quite liberal in trying to show acceptance of a wide variety of religious backgrounds, have made it clear that they treat secularity much differently. Whereas Muslim and Jewish groups have been welcomed by the Catholic administration of Notre Dame, efforts to form secular groups have been met with stern opposition. The tolerance on Catholic campuses for Islam and Judaism, religions that have historically been the target of open hostility and even violence from church leaders, is indeed revealing and surely a sign of the more pluralistic times, but the continued exclusion of atheist-humanist groups tells us even more. As religion diminishes in power, various religions that were once bitter enemies are more inclined to set aside differences so that they can circle their wagons together to fight the common enemy of secularism.

Proud secular identity is seen as very problematic in some schools, particularly those that are connected to religious institutions. Catholic colleges such as the University of Notre Dame, for example, though usually quite liberal in trying to show acceptance of a wide variety of religious backgrounds, have made it clear that they treat secularity much differently. Whereas Muslim and Jewish groups have been welcomed by the Catholic administration of Notre Dame, efforts to form secular groups have been met with stern opposition. The tolerance on Catholic campuses for Islam and Judaism, religions that have historically been the target of open hostility and even violence from church leaders, is indeed revealing and surely a sign of the more pluralistic times, but the continued exclusion of atheist-humanist groups tells us even more. As religion diminishes in power, various religions that were once bitter enemies are more inclined to set aside differences so that they can circle their wagons together to fight the common enemy of secularism.

Thus, though these major colleges hold themselves out as places that offer quality higher education for people of all faiths, the welcome mat is not really out for those of no faith at all. Secular student groups have also been rejected by other Catholic universities, including Dayton and Duquesne, as well as the world’s largest Baptist university, Baylor. Clearly, the feeling is that discrimination against atheist-humanist students is acceptable. Tolerance and ecumenical attitudes will dominate, except when the parties seeking inclusion are atheists and humanists. Interestingly, in the case of Dayton, even gay and lesbian groups are allowed, in direct conflict with Catholic teaching. This is just more evidence of the need for Secular Americans to raise their profile and fight unjustified vilification.

***

Secular Groups in High Schools

Within the last couple of years, the SSA has embarked on a major initiative that could become the most important campaign of secular activism to date. Although in its first decade the SSA focused solely on building college affiliates, it has now begun building a network of secular student groups in high schools. This seemingly simple act—creating groups in public schools for students who are atheist, agnostic, humanist, or otherwise nonreligious—could do more to validate the idea of being personally secular than anything else the secular community has done.

This has religious leaders understandably concerned. “In Chicago, we now have atheist clubs in high schools,” complained Cardinal Francis George in the National Catholic Reporter. “We didn’t have those five years ago. Kids I would have confirmed in the eighth grade, by the time they’re sophomores in high school say they’re atheists. They don’t just stop going to church, they make a statement. I think that’s new.”

Cardinal George is right—pride in secular identity among young people is new. Ironically, we can thank the religious right for making high school secular student groups possible. In particular, we can thank Jay Sekulow, the head of the American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ), an organization founded by fundamentalist televangelist Pat Robertson as the religious right’s answer to the ACLU.

Before Sekulow rose to prominence in the late 1980s, religious conservatives had been repeatedly frustrated in their attempts to inject religion back into public schools, as landmark Supreme Court cases in the 1960s had ruled that school-sponsored prayer and Bible study were unconstitutional violations of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. But Sekulow turned things around for the religious right. In the case of Board of Education of Westside Community Schools v. Mergens (1990), Sekulow successfully argued, using free speech principles, that a school district could not prohibit the formation of a Christian club. If schools allow the formation of various types of extracurricular student clubs, the argument goes, then it is not right to single out religious clubs as being impermissible. Since the Mergens ruling, Bible clubs and other voluntary Christian-oriented extracurricular activities have become commonplace in public schools across the country.

At first glance, this would seem like a clear victory for religious conservatives who wish to use public school facilities to create a culture of Christianity within those schools. Although membership in such clubs is voluntary, public schools in communities dominated by strong Christian churches would almost certainly see strong Christian clubs, resulting in a potent pro-Christian message and bias. And even in more pluralistic communities, a high school Christian club led by a charismatic student or teacher with missionary zeal could effectively proselytize on public school grounds.

What Sekulow and others on the Christian Right probably never considered, however, is that the Mergens decision opened the doors not just for Christian groups in public schools, but for other groups as well. If free speech standards dictate that Christian views on religion cannot be censored, then neither can the views of Hindus, Muslims, or Jews.

Or atheists.

Twenty years ago, it was rare to find a student secular group even on a college campus, let alone in a high school. But thanks to Sekulow, secular groups are now rapidly sprouting in high schools all over the country, protected by First Amendment rights. While many secular students face opposition from administrators when they attempt to organize student groups, they are able to threaten litigation, citing the Mergens ruling, to get them to back down. With high school secular groups normalizing secularity, children at a young age can now learn that their classmates and others in the community are proud nonbelievers, with admirable values, who reject ancient texts and supernatural explanations of the world.

Spearheading this effort is the SSA, which now has staff dedicated specifically to providing resources to high school students interested in starting groups. Also active in this area is the Center for Inquiry (CFI), which now operates high school secular student groups through its student arm, CFI On Campus. The SSA reported over sixty requests for applications from high school groups in the first few weeks after the program was announced in 2011, and it is likely that the number of high school groups will eventually outnumber college groups.

The significance of secular groups in high schools is hard to overstate. For a minority that has long been seen as outside the mainstream, as perhaps less patriotic (to those that believe we are one nation “under God”), the legitimacy that accompanies official recognition is invaluable. It becomes much harder to vilify atheists if they are meeting in the cafeteria after school, and even harder to do so when you realize that the cute classmate that you’ve been admiring since eighth grade is a member. Viva secularity!

Thanks to Sekulow and his efforts, Secular Americans are finally on an even playing field with Christianity in public schools. While it will be years before we see atheist groups in the same numbers as Christian groups, which have much greater wealth and resources, secular groups have much reason for optimism. When ancient, revelation-based religious texts are compared in a fair environment to a modern, nontheistic, naturalistic worldview, the SSA and its members will have little to worry about.

From the standpoint of Secular Americans, the need for these high school secular groups is indisputable. “Coming from southeastern North Carolina,” wrote Walker Bristol, a Tufts University student, “I am no alien to misconceptions regarding atheism.” In a May 2011 article in the New Humanism titled “Peers, Parents, and Popularity,” Bristol reported that his high school classmates responded with great concern when they suspected that he might be a skeptic, wanting to know if he still read the Bible and prayed. When he was in high school just a few years ago, the idea of high school secular groups was not even considered as a possibility, but now his younger brother and other students were taking steps to form an SSA chapter. Calling his younger brother’s work “inspiring,” he said, “We need secular students to be willing to stand unfettered by peer exile or parental disapproval. At the high school age, it may not always be best to suddenly and forcefully reveal your lack of belief to your friends and family. Nevertheless, if secular communities become as strong in high schools as the religious communities they might find themselves at odds with, the humanistic or atheistic student will find herself a part of a meaningful fellowship, welcomed and protected in the face of unfounded bias.”

***

All of this secular student activity—the popularity of secularity among young people, the college and high school groups, the chaplaincies, and now the field of secular studies—bodes well for the future, as it normalizes secularity, removes the mystery, and establishes it as familiar. Whereas secular students in prior generations may have apathetically drifted back to the family church or synagogue to get married, the solidification of secular identity among students makes other options, like ceremonies performed by humanist celebrants and chaplains, or even secular ceremonies conducted by civil officials, more likely to become the norm in the future. Secularity is now a real alternative, not just a default status for someone who has “lost” his or her faith; it offers a respectable identity and forward-looking life stance, not a stigma that is best hidden from public view. If successful, these students are the individuals who will escort the religious right off the stage of public influence and into the chapters of history books.

David Niose is president of the American Humanist Association, an attorney, and author of the popular Psychology Today blog “Our Humanity, Naturally.” He has appeared widely in national and international media advocating for secularism and humanism, including Fox News, BBC, NPR, and many others. Niose also serves as vice president of the Secular Coalition for America, a Washington-based lobbying group.