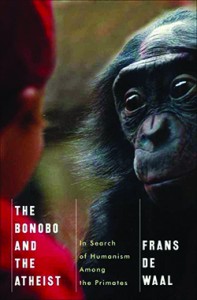

The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates

As handsome, beloved Amos lay dying, Daisy did her best to make him comfortable. Daisy seemed to grasp Amos’s situation and, being part of a tight-knit community, Amos could count on affection and assistance from relatives and nonrelatives alike.

Blind and deaf Kitty risked getting lost in a building full of doors and tunnels, so protective Lody gently led her to her favorite spot outside in the morning. And in the evening, taking her by the hand, he led her back indoors.

These are not-unusual examples of social life—the social life of captive apes. Amos, Daisy, Kitty, and Lody, along with many other members of the animal world, are described in expert detail by primatologist Frans de Waal in his latest book, The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates.

Throughout, de Waal demonstrates that compassion, understanding, and empathy are not uniquely human characteristics, nor are they the result of a religious belief. Rather, they’re an intrinsic part of our evolutionary past. In clear, concise prose, using engaging examples, de Waal shows that our lineage contains dominance and submissiveness, care and kindness, xenophobia and acceptance. All of these so-called human traits are natural behaviors that we share with other social primates.

Weaving the entertaining and heartfelt soap operas of captive and wild animals in and out of his discussions, arguments, and philosophical analyses (informed by anthropology, biology, psychology, and even art), de Waal provides plenty of evidence for the biology that underlies our human interactions. “Morality predates religion,” he contends, “certainly the dominant religions of today. We humans were plenty moral when we still roamed the Savannah in small bands. Only when the scale of society began to grow and rules of reciprocity and reputation began to falter did a moralizing God become necessary.” In de Waal’s view,

It wasn’t God who introduced us to morality; rather it was the other way around. God was put into place to help us live the way we felt we ought to. We endowed him with the capacity to keep us on the same straight and narrow that we’d been following ever since we lived in small bands.

In short, de Waal has no fear that society will fall apart or descend into utter chaos if our old superstitions disappear, since the compassionate ties of society are older than religion. It’s quite clear that he believes in the possibility of a more compassionate society, a humanistic society, and he wants us to join him. In The Bonobo and the Atheist, de Waal (an atheist himself) calls for “a reduced role of religion, with less emphasis on the almighty God and more on human potential.” What he takes issue with is dogmatism; both religious dogmatism and atheistic dogmatism. While his voice is mostly one of calm and reason in these shouty times, this book seems to have created a tsunami of opinions. This is unfortunate because the discussions over whether de Waal has been too hard on atheists have flooded the ether and it seems to have overshadowed the main gist of the book, which is to show that the seeds of our morality stem from our animal past and not from some religious belief.

Are the religious faithful going to read this book? I’m not so sure. And, if they do, will they change their minds? I don’t know.

For the most part the language is straightforward and accessible. The ideas and arguments are presented and strengthened through the use of various and well-explained examples. De Waal, the C.H. Candler Professor of primate behavior at Emory University in Atlanta and director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes Primate Center in Georgia, is passionate about his subject and the passion comes through in the writing. Whether they like it or not, scientists and experimenters have to engage with the public and de Waal is an excellent spokesperson for this journey.

Do I have any criticisms of the book? A few. Sometimes I found the side stories fun but irrelevant. Sometimes I felt as though I were being led off the path and had a hard time getting back on track. Sometimes I didn’t particularly agree with some of the statements he made (and how he could equate male circumcision with female genital mutilation I’ll never understand). Perhaps as well he could have given a more detailed (and possibly less dogmatic?) synopsis of why atheists have become so militant—particularly in the United States where one typically has to tie one’s coattails to God in order to be accepted, and certainly to be elected, and where resistance to evolution is rife.

While my criticisms really are minor, I do have one nagging problem. It comes back to Amos and Daisy and Kitty and Lody and all the other captive primates who help teach us so much about ourselves and are so mentally and psychologically close to us. If primates, and apes in particular, share so many of our emotions and awarenesses, should they be kept in captivity at all? While it’s clear that de Waal has the utmost respect for his subjects and has done a tremendous amount of work to ensure that a) invasive tests aren’t done on any captive primates; b) the animals live in spacious enclosures and are well fed and looked after (probably better than most captive animals); and c) the research is subjected to high levels of scrutiny, the animals are still being held captive. This book and many of de Waal’s other excellent books probably could not have been written without the examples of the benign experiments he (and many others) conducted on captive animals. So I’m left in a quandary. Is it justifiable to subject primates to captivity in order to write a fantastic treatise and tell us important facts about ourselves and our behaviors? I’m not sure. But I’m definitely leaning toward siding with the unfortunate captives.