Jefferson’s Women

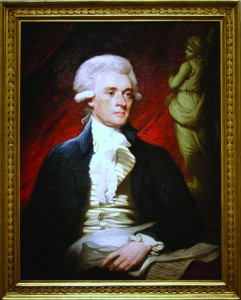

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown Thomas Jefferson was a private man who kept his personal life to himself, and yet today 18,000 of his letters exist in the public forum. In them, this farmer, architect, inventor, philosopher, politician, attorney, and “man of letters”—learned in all disciplines, a true visionary—expounded upon everything but his love life. This we know of Jefferson: he was a deist, a moralist, and a revolutionary. He wrote the Declaration of Independence and, in a letter to James Madison from Paris, suggested adding a Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution. He held positions of prominence within the newly formed United States (secretary of state, vice president, and president). He also wrote the book, Notes on the State of Virginia, and edited the New Testament into a volume he considered more believable, leaving out all the miracles and keeping what he considered the moral teachings of Jesus. He was proudest of founding the University of Virginia. And like all of the Founding Fathers, he’s become an icon, above the hoi polloi. But historians have had to connect the dots to give us a real picture of Jefferson the man—one who has become the model, not only of our intellectual and democratic ideals, but, inadvertently, of the often subtle racism that exists today.

In 1810, he listed his daily schedule in a letter to Thaddeus Kosciusko, the engineer from Poland responsible for the Colonies’ fortifications, “My mornings are devoted to correspondence, from breakfast to dinner I am in my shops, my garden, or on horseback among my farms. From dinner to dark I give to society and recreation with my neighbors and friends, and from candlelight to early bedtime, I read.” He got a bit closer to confiding more personal information to Dr. Vine Utley, of Lyme, Connecticut. In 1819 he wrote: “I have lived temperately, eating little animal food, and that not as an ailment but as a condiment for the vegetables which constitute my principal diet.” But despite this sharing of his personal life, he never wrote of the two women who were closest to him during his life—his wife and his slave mistress.

What manner of a man was the undisclosed Thomas Jefferson? Of course we know he was born just east of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the frontier in those days. His parents were aristocrats; his mother, Jane, was a Randolph, and his father, Peter, was a planter and surveyor whose map of Virginia was universally used in the colonial era. The elder Jefferson had an extensive library that included William Shakespeare and Jonathan Swift among others. Peter Jefferson died when Thomas was fourteen. During his formative years Thomas was tutored by the extremely conservative Reverend James Maury, an Anglican clergyman. Jefferson’s ideas about morality and religion would later jell in a way his tutor would not have applauded.

At seventeen, inklings of Jefferson the man began to emerge. It’s no surprise that Jefferson excelled in his studies at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, or that his interest in the opposite sex was piqued there. We can only speculate, of course, but historians have pointed to certain events and trends. When not at school, he and his best friend, John Page, exchanged chatty letters. During the school term, when not studying, they patronized the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg. There, Jefferson met the vivacious Rebecca Burwell and was smitten. He couldn’t help noticing her as she danced the quadrille or flirted with the men at the tavern. She was extremely attractive, and, at sixteen, of a marriageable age. Jefferson became infatuated, despite the fact that as the months passed he seldom saw her. Shy with young women, he wrote to his friend Page asking for advice. Page advised him to hurry and tell her his feelings.

Jefferson spent time planning how to do this and, in a letter to Page, recounted his disastrous attempt to follow through: “I had dressed up in my own mind such thoughts as occurred to me in a moving language…and expected to perform them in a tolerably credible manner. But, good God! …a few broken sentences, uttered in great disorder and interrupted with pauses of uncommon length were the visible marks of my strange confusion.” Rebecca had in the meantime turned seventeen and married another suitor not long after what Jefferson considered his debacle. That he could laugh at himself showed he was hardly devastated but viewed the matter as a learning experience.

The next woman’s name that appears on Jefferson’s historical record in a serious way is Betsey Walker. Undoubtedly other women caught Jefferson’s eye between his seventeenth and twenty-fifth years, but Walker is important because his relationship with her sheds insight into his sexual mores. Along with most men of the era, he believed intercourse was medically necessary for good health. When it came to medical subjects, Jefferson was a traditionalist and followed the medical advice of the day. He probably would not have consorted with women of “easy virtue” who could have left him with a sexual disease. Married women, it appears, could have been acceptable. Betsey Walker presented a golden opportunity.

John Walker, Betsey’s husband, had attended William and Mary with Jefferson. They were close enough that Jefferson was a member of their wedding party. Shortly afterward, John Walker was posted to Fort Stanwix, near present-day Rome, New York, and he asked Jefferson to look out for Betsey who stayed behind in Virginia. During the four months he was away, Walker asked Jefferson to visit her often.

Gossip maintained that Jefferson was, in fact, too attentive to Betsey. Years later, in a note to the secretary of the navy, Jefferson wrote, “I plead guilty…when young and single I offered love to a handsome lady. I acknowledge its incorrectness.” When rumors about his relationships with other women arose later on, he ignored or denied the allegations.

Unfortunately, no painting or detailed written portrait remains of the woman Jefferson courted seriously a few years later. Although people uniformly called her beautiful, we don’t know her height or the color of her hair or eyes, but we do know she was vivacious and talented. She had all the qualities Jefferson admired in a woman, indeed expected—that is, an ability to converse in a light but literate way, talent in one of the arts, and the ability to sew well and oversee a houseful of slaves.

That woman was Martha Wayles Skelton, widowed at the age of nineteen and left with an infant son when her husband, Bathurst Skelton, died in 1768. Martha’s father was John Wayles, a wealthy planter, slave dealer, and lawyer, who had been married four times by the time Martha was thirteen. She hadn’t liked any of her three stepmothers. Wayles, perhaps as a consequence, gave up on marriage but took to his bed a slave named Betty Hemings. She was half white, her father having been a white ship captain, her mother a full-blooded African. Betty’s ongoing affair with Wayles produced six children, all one-quarter black, all half-siblings of Martha. Betty Hemings could very well have been like a surrogate mother to her; Martha had known her longer than any of her three stepmothers.

Jefferson was enthralled with Martha, who was twenty-two or twenty-three when he began courting her. Her beauty and accomplishments fit his desires perfectly. Not only did she love music, as did he, she was proficient on the harpsichord. They often played duets, with Jefferson playing the violin. They also sang, talked, and flirted. One of Jefferson’s favorite novels was Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne, whose satirical skits, essays, and sketches were filled with sexual innuendo, sometimes including witty obscenity. Whether Martha shared Jefferson’s appreciation of the book at the time is unknown, but her familiarity with it is expressed in later writings. Although it’s true she had many other suitors, it seems clear that Martha and Jefferson were a love match.

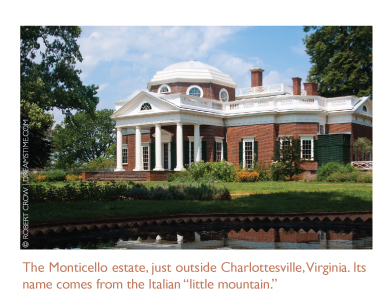

Snow covered the Virginia countryside January 1, 1772, when Jefferson, twenty-nine, and Martha, twenty-four, took their oaths at The Forest, the Wayles’ plantation, and honeymooned in the South Pavilion at Monticello. (The rest of the grand house was not yet finished.)

With marriage, Jefferson’s wealth increased exponentially. In addition to land and other slaves, Martha brought all the Hemings family to Monticello, including the children that predated Betty’s liaison with Wayles. Undoubtedly the bonds between the young heiress and the Hemings family were strong. Probably because of the blood relationship, no Hemings ever worked in the fields at Monticello. Until they were fourteen years old, the children had few chores and mainly ran errands. After that the boys were taught a trade while the girls did light sewing and baking at the great house.

With marriage, Jefferson’s wealth increased exponentially. In addition to land and other slaves, Martha brought all the Hemings family to Monticello, including the children that predated Betty’s liaison with Wayles. Undoubtedly the bonds between the young heiress and the Hemings family were strong. Probably because of the blood relationship, no Hemings ever worked in the fields at Monticello. Until they were fourteen years old, the children had few chores and mainly ran errands. After that the boys were taught a trade while the girls did light sewing and baking at the great house.

Jefferson characterized his years with Martha as “unchequered happiness.” Although he and the other founders often traveled to Philadelphia during that time, he invariably stated his desire to be home. At Monticello, he entertained visitors in his erudite fashion and Martha, adding her genteel, charming ways to his table, expanded her own horizons entertaining foreign visitors. In charge of the house slaves, she oversaw the making of beer, soap, candles, and the sewing of household goods. She also supervised the baking, and at times read recipes aloud from cookbooks. An ardent spouse, she bore Jefferson six children, two of whom lived to adulthood. But each pregnancy dragged her down physically, and after ten years of marriage, on September 6, 1782, she died at age thirty-four, having begged Jefferson not to force a stepmother upon her children.

This request could have been taken to mean that if he did remarry, he should be the final arbiter regarding the children. Instead he took the words to mean he should not remarry and, indeed, he never did.

Years later, a note written by Martha Jefferson was found that read: “Time wastes too fast. Every letter I trace tells me with what rapidity life follows my pen. The days and hours of it are flying over our heads like clouds of a windy day never to return more—everything passes on…” This quote was finished by Thomas Jefferson: “and every time I kiss thy hand to bid adieu, every absence which follows it, are preludes to that eternal separation which we are shortly to make!” The words, so filled with meaning, were taken from Tristram Shandy.

The depth of Jefferson’s love for his beloved wife can be seen in the paucity of his writing about her. She meant too much for him to eulogize her. He merely wrote in his journal that she had died. Consistent with his beliefs, he did not look to religion for consolation in grief. But he did turn to his daughter, Patsy, and the two became very close.

Five years after Martha died, Jefferson represented his new country in Paris. The French were a revelation. Although he undoubtedly knew they were against slavery, he found France different in other ways, too. The women of the continent surprised him with their sophistication, pleased him with their wit and charm, and confounded him with their political knowledge. In his opinion, women were to stay out of politics. During his last year in Paris, he wrote to Ann Bingham, a Philadelphia beauty, “The gay and thoughtless Paris is now become a furnace of politics. Men, women, children talk nothing else. But our good American ladies, I trust, have been too wise to wrinkle their foreheads with politics. They are contented to soothe and calm the minds of their husbands returning ruffled from political debate. They have the good sense to value domestic happiness above all other.”

Still, the Parisian women, more relaxed in affairs of the heart than American women, intrigued Jefferson. Erotica permeated Europe, especially in the French culture where, for example, women wore gowns cut exceedingly low in front. Also, his dear friend Lafayette, a hero of the American Revolution who was happily married, had a mistress. Jefferson couldn’t help but be interested and confused at the same time.

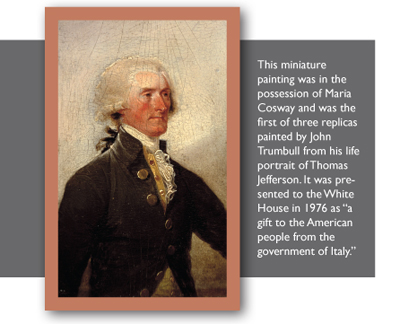

At first Jefferson socialized primarily with John and Abigail Adams, who were also in Paris. Matching wits with Abigail, whose mind was unmatched by most women Jefferson knew, gave him intellectual stimulation, and Abigail’s rather prudish ways (she was shocked at what dancers wore in the ballet) insulated him from French society. But when the Adamses went to London, Jefferson plunged into Parisian social life. “Here we have singing, dancing, laughter and merriment. No assassinations, rebellions, nor other dark deeds,” he wrote to Abigail. “When our king goes out they go down and kiss the earth where he has trodden, and then they go to kissing one another. And this is the truest wisdom.” He soon met and became infatuated with Maria Cosway, wife of the famous British painter, Richard Cosway. By this time Jefferson was forty-four; it had been five years since he’d lost Martha, and he was ready for a romantic interlude.

At first Jefferson socialized primarily with John and Abigail Adams, who were also in Paris. Matching wits with Abigail, whose mind was unmatched by most women Jefferson knew, gave him intellectual stimulation, and Abigail’s rather prudish ways (she was shocked at what dancers wore in the ballet) insulated him from French society. But when the Adamses went to London, Jefferson plunged into Parisian social life. “Here we have singing, dancing, laughter and merriment. No assassinations, rebellions, nor other dark deeds,” he wrote to Abigail. “When our king goes out they go down and kiss the earth where he has trodden, and then they go to kissing one another. And this is the truest wisdom.” He soon met and became infatuated with Maria Cosway, wife of the famous British painter, Richard Cosway. By this time Jefferson was forty-four; it had been five years since he’d lost Martha, and he was ready for a romantic interlude.

Jefferson liked teasing and flirting with Maria Cosway. She had an Italian background, laughed easily, and flirted enthusiastically. Jefferson was enchanted. They spent many hours together while her husband attended to his art. (In addition to serious canvases, Richard Cosway painted snuff-boxes that bore pornographic images.)

Maria seemed like the perfect woman for Jefferson; he could stay true to his deathbed promise to Martha and still indulge his erotic self. With Maria he rode through the parks and down the boulevards, danced at balls, played cards, and romanced her in notes. Once while out strolling, whether to prove his physical prowess or virility, Jefferson tried to leap over a fence. Catching his foot, he came down on his hand, injuring it. The event coincided with Maria’s husband leaving Paris, so we don’t know how sympathetic the lady could have been. Although her husband was remarkably tolerant, when he left for home, he wanted her with him.

Jefferson’s letters to Maria became more passionate as well as literary. In a treatise that verged on a polemic, he spoke of his head and his heart, using them to illustrate his physiological and psychological distress. To which should he listen, he asked. He worked on this now-famous letter for a full week. She answered without once referring to his head and heart assertions. And while Jefferson had been struggling over the wording of his important letter, Maria had been spending time with the American painter John Trumbull. Upon learning of this, Jefferson, in a pique, didn’t write to her but addressed attention to her in a letter to Trumbull, saying something akin to “give Mrs. Cosway my regards.”

In a quandary about the lady, he set out on an extended tour of the continent and was gone two and a half months. Not once during that time did he write to her, although he kept copious notes of the flora and fauna he saw along the way. Back in Paris, he again wrote to Maria. He alluded to Tristram Shandy, using references to noses in place of a more erotic appendage. Maria seemed rather bored with the letter and upset with him. Why hadn’t he written to her while he was away? And what was this about noses? It seemed she had not fully understood the wordplay, or chose not to. Either way, their romance slowly faded.

Jefferson’s daughter, Patsy, had already been in Paris with him, and he now sent for his daughter Polly, asking that she be accompanied by a woman servant. Instead, one of the Hemings children, fourteen-year-old Sally, was sent. We don’t know when Jefferson and Sally became intimate, but we do know that she was pregnant when they returned to Monticello.

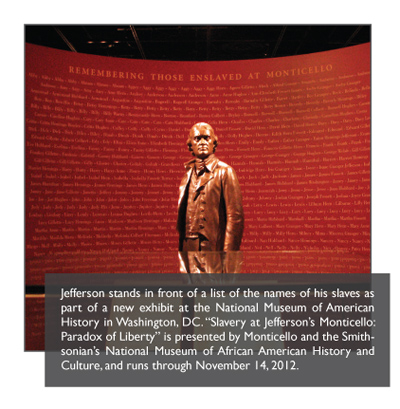

Before a 1998 DNA analysis showed a match between the Jefferson male line and a Hemings descendant, scholars, historians, and the public denied that a romantic relationship between Jefferson and his slave could have happened. As Joseph Ellis notes in American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (1998), Jefferson had become not only an icon but a myth, larger than life. This thinking temporarily blinded people to reality. Today, however, we can look to other events and speculate how his relationship with Sally Hemings may have played a role. His beloved daughter, Patsy, for example, married just two months after returning home from Paris. There is no indication that she and her husband-to-be, Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., had been eager correspondents while she was away, and there is no indication that they had been anything more than friendly cousins before she went to France. Could she have been afraid of losing her number-one spot with her father? Or can we attribute her actions to shock and anger upon learning of her father’s affair with a slave she’d known her entire life?

Such a reaction certainly would have echoed the hypocritical and confusing feelings the majority of Americans held about slavery during those colonial and post-revolutionary years. Abigail Adams, for example, was a devout abolitionist but, after seeing Othello, wrote that she was quite undone seeing a play about a marriage between a black man and a white woman. She felt horror and disgust every time she saw the Moor touch the gentle Desdemona. Abigail was no different than most of her peers. When she referred to Hemings as “the girl” rather than using her name, it was hardly seen as strange.

At Monticello, Sally Hemings was known as “dashing Sally” and was said to have a pleasing disposition. Beautiful and extremely light-skinned, she bore a probable resemblance to her late half-sister, Martha, Jefferson’s beloved wife. Hemings could also read and write and had learned to speak French while in Paris.

Today we might ask, why didn’t Hemings remain in France where she could have been a free woman? For one thing, France had become chaotic. The storming of the Bastille had taken place while she was in Paris. Considering her age and that most of her life had been spent at Monticello, returning was not a hard choice. At the plantation Hemings had status, a status that would undoubtedly grow when she returned as Jefferson’s lover. Hadn’t that been her mother’s position at the Wayles plantation? Also, Jefferson agreed any children born of their union would be freed when they turned twenty-one.

Today we might ask, why didn’t Hemings remain in France where she could have been a free woman? For one thing, France had become chaotic. The storming of the Bastille had taken place while she was in Paris. Considering her age and that most of her life had been spent at Monticello, returning was not a hard choice. At the plantation Hemings had status, a status that would undoubtedly grow when she returned as Jefferson’s lover. Hadn’t that been her mother’s position at the Wayles plantation? Also, Jefferson agreed any children born of their union would be freed when they turned twenty-one.

So while there was without question a power imbalance between the elder statesman and his young slave, coercion seems to have played a very small part. It’s also not inconceivable that Sally Hemings was in love with Jefferson. He had a good physique, rode horseback well, and could be charming as well as didactic. While in Paris, he had seen that Sally received a wage, had better clothing than she’d worn in Virginia, and was inoculated against smallpox. It’s also well documented that Jefferson liked playing the patriarchal figure at Monticello. Hemings, whose father, John Wayles, died shortly after she went to Monticello at the age of two, very likely looked upon Jefferson as a father figure and could have been flattered that this great man, honored not only in his own country but also in France, had an interest in her.

Jefferson’s devotion to Sally Hemings lasted all his life. That he never wrote about her is not surprising. She was at once too important to him and not important enough; despite her role as a sympathetic ear and loving bedmate, she was still a slave. If his beliefs about her status changed at all during the years, there is no evidence of it.

In his 1781 book, Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson wrote that he did not believe blacks were equal to whites. But because they were human beings, he insisted slaves should be respected and treated well. He argued all his life that slavery should be abolished, but that emancipation should be gradual and that former slaves should live separately from whites. His belief that the two races could not live together harmoniously was shared by his friend, James Madison. Madison never freed his slaves, and he illustrated his stance by adding that they couldn’t be freed “unless they are permanently moved beyond the region occupied or allotted to a white population.”

Although the inherent racism in their beliefs is clear to us today, Jefferson and Madison were considered very progressive at the time. But their liberalism had limits. Even George Washington, the only founder to eventually free all his slaves, made sure that when slaves accompanied him to northern cities they returned with him to Mt. Vernon before they could become free. He and his wife, Martha, owned slaves separately. In his will, George freed his slaves but stipulated they would not be free until after Martha’s death. Convinced that some of these slaves wished her dead, Martha freed her late husband’s 123 slaves during her lifetime (but she never believed slavery was wrong). Moreover, all of the men who met in Philadelphia to write the Constitution agreed to stipulate that slaves were to be counted as three-fifths of a person. As president, James Monroe, whose beliefs echoed Jefferson’s and Madison’s, saw an initial group of American slaves settled in Liberia in 1820. (Thousands followed later, and Liberia became independent in 1847.) But most of the South believed, like Martha Washington, that slavery was biblically inspired, and the gulf between the South and their fellow Americans in the North grew larger.

Today, when African-American representatives of the government are spit upon and verbally assaulted, or when more subtle or more blatant acts erupt, the legacy of the past cannot be dismissed, and our most revered historical figures must bear some blame. We could say that Jefferson and the others reflected the social and economic mores of the times, and in a way that’s true. But their thinking had serious limitations and lasting implications. We see this thinking now, not in blatant violence like the lynching of black people or the violent reactions of some whites during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, but in less easily discernible ways, like the slow pace we took in eliminating “separate but equal,” in getting rid of poll taxes, or integrating neighborhoods. Today blacks are still paid less than whites in many instances. Discrimination in housing, schooling, and voting still takes place. As a society, we routinely deplore racial violence and say we are not prejudiced, but racism still exists. For instance, U.S. presidential candidates routinely speak at universities, schools, and public venues that discriminate against African Americans. Also, too often religion and bigotry go hand in hand. And when the main objective of a political party is to “make Barack Obama a one-term president,” few people protest, even those who support him. So if we’re being honest, we must contend that otherwise admirable historical figures like Jefferson, Madison, Washington, Monroe, and Abigail Adams contributed to the legacy of racism.

It is now accepted as fact by most historians that Sally Hemings bore six of Jefferson’s children, four of whom survived to adulthood—Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston, all named by Jefferson after his best friends. (Was James Madison amused, annoyed, or was it a habit friends indulged in even as they indulged their libidos?) Jefferson’s belief in racial superiority is evident in his theory about the offspring of mixed-race couples, including his own. He felt that an infusion of white blood could make a person half black, and another infusion would make their offspring one-fourth black. Sally Hemings was one-fourth black. Offspring of a so-called quadroon and a white man would, in Jefferson’s thinking, make them equal to whites. And yet his children by Sally were never treated as completely equal. The contradictions were rife.

For example, although they were not part of the social life at Monticello, Jefferson’s slave children lived there and were seen by visitors. At a time when not all Americans could read or write, Jefferson saw that all the Hemings could. He also arranged for the boys to learn a useful trade. As for the Hemings women, none married other slaves at Monticello but they did have liaisons with white men who visited frequently, or who worked on the plantation. One Hemings woman married a house slave from another plantation.

Keeping his promise, Jefferson gave all of Sally Hemings’ children their freedom. Madison, whose full name was James Madison Hemings, reported that his father was not demonstrative, but was kind. Displays of affection were reserved for his white children. Two of Jefferson’s children from Sally “passed” and lived as white. Beverly, Jefferson’s eldest slave child, went to Washington as a white man and married a white woman. The beautiful Harriet, who, according to her brother Madison, was as white as anyone, was given stage fare to Philadelphia and fifty dollars, a very handsome sum at the time. She eventually married a white man of good standing from Washington, DC. Madison and Eston were freed when Jefferson died at the age of eighty-three on July 4, 1826.

Sally Hemings was not freed in Jefferson’s will. Undoubtedly he feared adding to the speculation about his relationship with her, which he and most people had ignored or denied. It’s believed that he arranged with Patsy to give Sally her freedom. Eight years after he died, she did so. In the interim, Sally lived in Virginia with her two sons, Madison and Eston. No one ever contested her right to live and act as a free person, undoubtedly a mark of respect for Jefferson. She stayed with her sons until her death in 1836. At times Harriet and Beverly visited, but these visits grew fewer and then stopped as slavery and states’ rights became a volatile issue in the more ambiguous colonial states.

So what kind of a man was Jefferson? Was he conflicted ideologically? An enlightened lover stifled by his very public place? Despite any desire for privacy concerning his private life, a public figure as complex and respected as Thomas Jefferson could never achieve it, even almost two centuries after his death. Nor should we wish he ever did or would, because the more we know about our heroes, for all their complexities and contradictions, the better we know ourselves, and the better positioned we are to honestly assess where we’d like to be as a society.