Blasphemy, Free Speech, and Rationalism: An Interview with Sanal Edamaruku

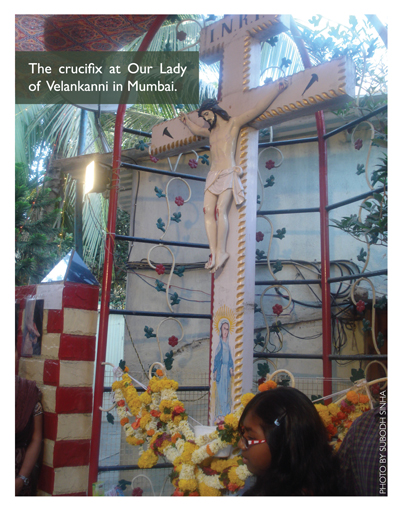

Sanal Edamaruku is a world-renowned author and rationalist currently facing a maximum sentence of three years in prison plus fines for criticizing the Catholic Church. As president of the Indian Rationalist Association, he is a fixture on Indian television where he provides a skeptical view about alleged miracles and paranormal claims. In 2012 Edamaruku investigated what was being called a miracle: a crucifix dripping water at Our Lady of Velankanni Church in Mumbai. He quickly discovered the dripping was actually caused by water seeping through the wall onto the crucifix. Edamaruku reported his results on TV-9 and criticized the Catholic Church for “creating” the so-called miracle and being “anti-science.” In response, the church demanded an apology and its supporters filed official complaints against Edamaruku. He was charged with violating 295(a) of the Indian Penal Code, also known as the “blasphemy law,” which prohibits “deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” His lawyers are arguing that the law infringes on free speech and are requesting the courts declare the law unconstitutional. Meanwhile, he was refused bail and fled to Europe. In this interview he speaks about his work, his family, the criminal charges, and the dangers of the “blasphemy law.”

The Humanist: Tell us a little about your background.

Sanal Edamaruku: I was born in Kerala, India, and lived there until I came to Delhi in the late 1970s to study at Jawaharlal Nehru University. My parents were rationalists who came from different religious backgrounds; my father, Joseph Edamaruku, came from a Syrian Christian family. One of his uncles was a bishop. My mother, Soley Edamaruku, came from a Hindu family. Both my parents are from Edamaruku village and adopted the village name as their surname. Because they both came from religious families, the young couple faced a lot of problems and dangers when they decided to marry. The events around my birth were something like an acid test for their commitment to each other and to rationalism. When my mother was nine months pregnant, they were invited to my father’s parents’ house for the birth. They stayed there peacefully for some time. But the day my mother went into labor and my father happened to be out of the house, the family suddenly tried to force her to convert to Christianity. That night my parents made the hard decision to leave. They wandered—my mother travailing—through a rainy night not knowing where to go. I was born in the early morning hours under the open sky and rain before they could reach my maternal grandparents’ house.

The Humanist: What a vivid (and oddly familiar) beginning! What was your childhood like from there?

Edamaruku: My childhood was very colorful. At an early age, I became involved in traditional Kerala music, dance theater, and the world of mythology. Over many years, I studied and performed Kathakali (the highly stylized classical Indian dance-drama) with great enthusiasm—and success. I was also a passionate reader, making my way through my father’s diverse library, and was lucky to get acquainted with great thinkers, writers, and social reformers of that time, as our house was a meeting point and a place for intense discussions.

Though I grew up without gods or religious indoctrination, I wasn’t pressed into rationalism either. My parents wanted me to have every option and make my own decision, which I did at the age of fifteen. It was triggered by a dramatic event. There was a young woman in our neighborhood named Susan who was a nationally acclaimed athlete and who later developed blood cancer. Her deeply religious family did not allow any medical treatment but tried to “cure” her with prayers while we helplessly watched her die. Her death shook me deeply—and finally made me an active rationalist. Soon after, I founded a rationalist student organization and launched anti-superstition campaigns.

The Humanist: What were your academic interests growing up? Who are some of your intellectual influences?

Edamaruku: I was always interested in understanding and explaining how things worked and how they were connected. I was always confident that science would explain everything—if not today, then tomorrow. I was very interested in history and studied political science at the University of Kerala and international politics at the School for International Relations at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. Among the important intellectual influences in my young years were Jawaharlal Nehru, Rabindranath Tagore, and Periyar E.V. Ramaswamy, as well as Robert G. Ingersoll, Joseph McCabe, Lewis Henry Morgan, William Winwood Reade, H.G. Wells, Charles Bradlaugh, and Bertrand Russell.

The Humanist: Your father was excommunicated from the Catholic Church for writing the book, Jesus Christ a Man. Why?

Edamaruku: Once my father allowed himself to think critically about the Bible, he began step by step to confute Christian teachings and wrote the book. When he distributed the first handmade copies of Jesus Christ a Man, he stirred up a hornet’s nest. His uncle was a bishop, after all, and my father was seen as a stain on the family’s orthodox reputation. Members of his family demanded that he apologize, but he refused. Then they tried to get him assassinated, forcing him to flee. A Hindu scholar gave him asylum and allowed him to live in his huge library, where my father came upon the Complete Works of Robert Green Ingersoll.

The Humanist: Your father was arrested on several occasions. Why did he become a target?

Edamaruku: In 1970 my father had managed to buy a small printing press, and was arrested in the midst of preparations for republishing his controversial book. Some meaningless charges were used as a pretext for the arrest: he knew a person who was accused of being a “radical.” The police held my father for several days and tortured him brutally, threatening to break his fingers so that he wouldn’t be able to write again. Then they burnt the manuscript of his book and took away the printing press.

In 1975 my father was arrested for the second time. It was during the Emergency rule in India, and at first it seemed his arrest was connected with his work as the editor of a newspaper. But he was the only journalist in Kerala who was arrested during that time. It actually had to do with his first arrest, after which my father wrote a book exposing the officers who had tortured him. He was released only after the chief minister of Kerala intervened. Some of the police officers were later punished.

The Humanist: Turning to your own activities, one of the things you do is visit rural regions and encourage skepticism for the gurus, “miracle workers,” and spiritual leaders collectively known as godmen in India. Have you been successful in teaching critical thinking?

Edamaruku: Our village campaigns are very successful. One of the techniques we’ve developed to break the spell of superstition is what we call Rationalist Reality Theatre. We create an illusion of a godman’s supernatural powers at work, then we take the audience by surprise by exposing the tricks behind the “miracles.” Many feel spontaneously relieved and laugh before they notice there’s a problem: their sudden realization of the absence of supernatural forces is contradicting their ironclad, fear-burdened beliefs. But with some encouragement, it can be made fruitful and open their minds, enabling them to start questioning the “unquestionable.” Of course, there are people who are too fearful to leave their mental prisons. One has to consider that there are many forces on the other side working actively and relentlessly against reason.

Generally, though, once triggered, critical thinking multiplies. This is especially true for television viewers from all walks of life who simultaneously experience a flash of reason in their homes. Some years back it was reported that after one of my TV appearances, an early morning bus in Mumbai had to stop because the driver got afraid when more than one hundred passengers indulged in a passionate discussion about the previous night’s program, on which a Hindu tantric had tried to kill me with mantras.

The Humanist: What exactly happened on the show?

Edamaruku: The program started with a superstitious politician claiming that her political enemies were using tantric powers to inflict harm on her. TV tantric Pandit Surinder Sharma, who was my opponent in the discussion, used the opportunity to boast that with his alleged powers he could kill any person within three minutes just by chanting special mantras. I spontaneously offered myself as a test subject, and Sharma agreed hesitantly. Nothing happened after three minutes. On the tantric’s demand, the show was continued into the night under the open sky, where he performed his great destruction ritual against me. Not only did he chant mantras, he opened his bag of special tricks to make me lose my balance, which included brandishing a knife in front of my face. After hours the anchor officially declared Sharma a failure. He looked depressed, but still insisted that I was to die the next day or at least within a week. I think he must have been used to people fainting in fear when he chanted his mantras and was really thrown by what was happening; to some degree, he must have believed he had special powers.

The Humanist: Have you ever heard a guru admit he was wrong or that he or she may not have special powers?

Edamaruku: No, and it’s unlikely to ever happen; it would be personal, social, and professional suicide. After all, what is the future of a holy man who admits he’s not holy? There are thousands of holy men and women in India who are, on one hand, clever professionals who know they’re betraying the gullible; on the other hand, some are psychopaths to a certain degree who believe their own claims. This mixture seems to be the secret of the trade. What can we do with these people? I don’t have much hope in educating them. But we have to discourage young people from following in their footsteps.

The Humanist: You’ve been charged for blasphemy under Section 295(a) of the Indian Penal Code, which makes it illegal to “outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” Can you talk about the origins of this law?

Edamaruku: Indian blasphemy laws are relics of colonial legislation and have a long history of abuse. In the decades since independence, they’ve been regularly used to hound and silence intellectuals and artists who question religious beliefs. What’s dangerous is that anybody can easily launch a complaint against whomever he wants for violating his religious feelings. And on the basis of such a complaint, the police can arrest and hold the suspect until he’s acquitted by a court of law, which can take years. So the real danger isn’t so much the verdict as the pre-trial “punishment.”

The Humanist: Has anyone been successfully found guilty under 295(a) since independence?

Edamaruku: Yes, there have been many convictions. Take the famous case against E.V. Ramaswami Naicker, a rationalist leader and politician from Tamil Nadu. After being acquitted by the lower courts, he was finally convicted by the Supreme Court because he broke a clay idol of Ganesh (a Hindu god) in 1958. There are recent cases as well, and many books have been banned for blasphemy, most famously Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses.

The Humanist: In March 2012 you investigated a crucifix that was dripping at Our Lady of Velankanni church in Mumbai, and you identified the source of the drip as resulting from a clogged drain. Did the church dispute that this was the source of the water?

The Humanist: In March 2012 you investigated a crucifix that was dripping at Our Lady of Velankanni church in Mumbai, and you identified the source of the drip as resulting from a clogged drain. Did the church dispute that this was the source of the water?

Edamaruku: They angrily refuted the facts without being ready to have a closer look. On the controversial TV program, Catholic leaders even disputed the scientific validity of capillary action. In the face of our documentation, they later found it prudent to modify their position, ignoring the facts and customizing it as a political weapon.

The Humanist: Has the Vatican in Rome made any statements about this?

Edamaruku: The Vatican keeps mum even though more than 10,000 signatories to a London-based human rights petition—some of them prominent personalities—have demanded a clarification from the Vatican as well as from the Catholic Church of India. However, the auxiliary bishop of Mumbai made official statements in the press saying that he publicly “rejoiced” and praised the “courageous” Catholic laity leaders who had filed police complaints against me.

The Humanist: Why did the police raid your home in early July? Was this expected?

Edamaruku: Starting in April, I received regular phone calls at night from one officer at a Mumbai police station who pressed me to come to Mumbai to face arrest. He refused to give details about the case against me. Strangely, I had never received any written notice, so I had no chance to file an answer. According to the police officer, there was no need for any answer, as he had orders to arrest me under any circumstances. Frankly, I didn’t take those calls very seriously. It was only when the pressure increased and media people confirmed that they’d seen the charge sheet that I engaged my lawyer. Still we didn’t really expect that I could be arrested. It seemed too absurd.

The Humanist: What’s the current status of the case?

Edamaruku: The trial has yet to begin, and the Delhi and Mumbai high courts have refused on technical grounds to grant me anticipatory bail. I’ve received no invitation to give my statement. Of course, in this case all the proof is public. The “corpus delicti” is the TV program posted on YouTube. When the trial opens, we wish to see the representatives of the Indian Bishops’ Conference in the witness box. It may become an interesting historic event.

The Humanist: Law enforcement in India has come under scrutiny recently following the gang rape and death of a young student on a Delhi bus. The police were criticized for their slow response and inadequate investigation, and there have been calls for reform. Meanwhile, Delhi police have used government resources to investigate you, press charges, and have made multiple visits to your home. Given your own experience with the police and courts in India, do you think law enforcement needs to be reformed?

Edamaruku: There is an urgent need to reform the police functioning and law enforcement in India. When there is pressure from politically or religiously powerful interests, police action is unusually hasty and senseless. In my case, the police collaborated with the fanatics and religious zealots to investigate and harass me for exposing a homemade miracle, for telling some well-known historical facts, and for using my faculties of critical inquiry.

Unbridled power given to police to enforce the Indian blasphemy law is unsuitable for a country that respects human rights. Proper monitoring of police functioning and control by a wiser body in cases like this are necessary. At the same time, it’s sad when police are inactive in countering real crimes and violations of human rights in India, as happened in the recent notorious cases.

Unbridled power given to police to enforce the Indian blasphemy law is unsuitable for a country that respects human rights. Proper monitoring of police functioning and control by a wiser body in cases like this are necessary. At the same time, it’s sad when police are inactive in countering real crimes and violations of human rights in India, as happened in the recent notorious cases.

The Humanist: Should the government have any role in protecting religion in India, which has suffered from religious conflicts throughout its history?

Edamaruku: The government has the duty to protect religious and nonreligious citizens, but not religion. Religion is a private matter.

History shows that most people in India are ready to tolerate others’ religions, to live and work peacefully together. But religious conflicts have always been created to play politics, and there’s no strong political will to end this old game as politicians of all parties prefer to reap its fruits. In short, the blasphemy law encourages abuse. It even offers a legal cover for crimes against the Constitution of India, Section 51A of which states “It shall be the duty of every citizen of India …(h) to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform.” Our aim at the Indian Rationalist Association is to encourage and support people to fulfill this very duty, and it’s exactly what I did in Mumbai.

The Humanist: What can people expect from you in the future? Any upcoming events or publications?

Edamaruku: I’m waiting to go back to India and continue my work. Thanks to modern communication, I’m able to keep in close contact with my rationalist colleagues and guide their manifold works from here. There is a new consciousness of strength and focus growing in the movement after the attack against me. I think that’s a very positive development. In the meantime I’m working on two books, and I’ve had the opportunity to give lectures and have fruitful meetings with rationalists, humanists, skeptics, freethinkers, and atheists all over Europe. I hope these months of intense cooperation are a formation stage for great new things to come.![]()

Ryan Shaffer is a historian and writer. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Stony Brook University.