Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation

BOOK BY LEIGH ERIC SCHMIDT

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2016

360 PP.; $35.00

WHAT INITIALLY DREW ME to read Village Atheists was curiosity about life and challenges for secularists living in the United States more than a century ago. Without overwhelming the reader with countless players from that time, in four meaty chapters Leigh Eric Schmidt gives us “a pointillist group portrait, looking closely at a small handful of figures, all of whom exemplify critical aspects of American secularist experience.”

Schmidt starts his examination with Samuel Porter Putnam’s contributions to and participation in secularist society, which were far from consistent or linear. Indeed, Schmidt notes, “Constancy was not the mark of [Putnam’s] secular pilgrimage—or of most secular pilgrimages of the era. Putnam zigzagged his way out of and into and out of and into any number of things—atheism included.” By weaving Putnam’s interactions with the work of other notables of the time—Horace Bushnell, Francis Ellingwood Abbot, and Robert Ingersoll, to name a few—Schmidt whittles Putnam’s robust biography down to fifty dense pages. Schmidt leaves no stone unturned, covering everything from Putnam’s book to the downfall of his marriage.

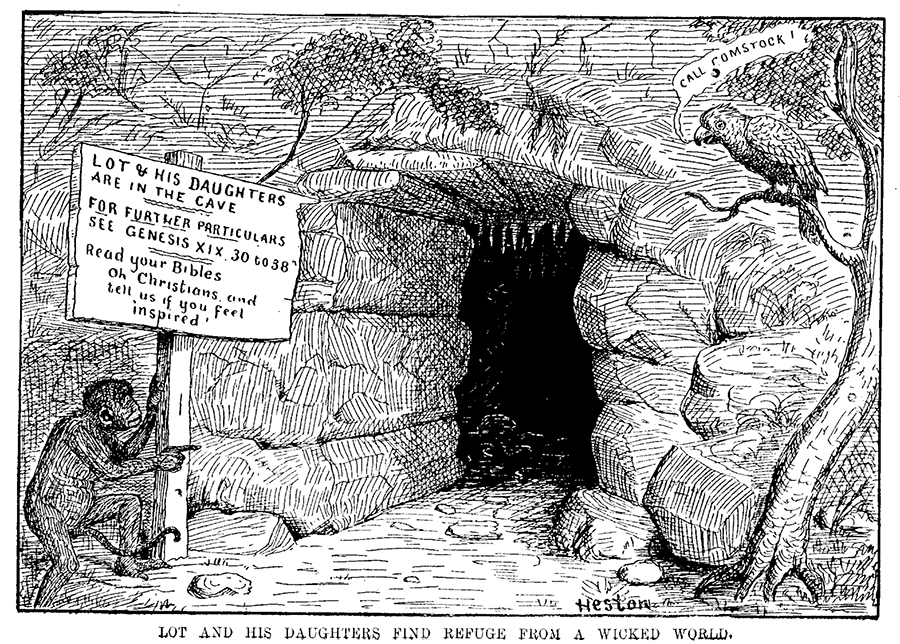

In the next chapter, we are treated to a visual break from text with the many illustrations of freethinking cartoonist Watson Heston, the “artist-champion of the secularist cause.” Through some of his own hardscrabble perseverance, and with the help of an old friend, Heston’s drawings made their debut in the Truth Seeker weekly newspaper starting in May 1885. Until that point, the Truth Seeker almost never featured any “visual embellishments” and had a largely “unadorned appearance.” Heston’s first caricature for the paper, entitled “The Modern Balaam,” broke that mold and filled half the cover page. Including Heston’s drawing proved to be a smart move for the Truth Seeker with immediate increased demand for the issue and reader requests for alternate versions of the image to display and share.

Heston continued to draw for the Truth Seeker through April 1900, creating more than 600 covers, plus hundreds more “comic Bible sketches” for the back page. Additionally, the publisher of the weekly produced four stand-alone collections of Heston’s cartoons between 1890 and 1903, further solidifying his place at the top of “incomparable iconography of American secularism.”

More than four dozen of Heston’s cartoons appear throughout Village Atheists, with the bulk of them appearing in Chapter 2. Schmidt provides rich descriptions of and historical context for the drawings, highlighting the many themes Heston tackled within the context of religion, like state-endorsed observances, women’s rights, and racial politics. But Heston wasn’t without social backlash or his own flaws. He also drew “coarse, derogatory” Hebraic portraits and possessed an abrasive lack of tact, and Schmidt carefully rounds out Heston’s reputation by noting these shortcomings. The story of Heston’s career from start to finish and the black-and-white illustrations featured in Village Atheists are sure to satisfy any fan of political cartoons.

Originally printed in the late 1800s in Truth Seeker weekly: Lot and his daughters find refuge from a wicked world, cartoon illustration by Watson Heston.

Once a devoted preacher in the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Charles B. Reynolds, who is the subject of Chapter 3, was not a likely blasphemer. Yet, in the summer of 1886 Reynolds proclaimed at a public lecture to be “a Freethought evangelist” and soon found himself under arrest and charged with blasphemy. That is, “contumaciously reproaching the being and existence of God [and] the scriptures as contained in the books of the Old and New Testament.” What ensued after the charge was lengthy litigation and a high-profile trial the following year. Robert Ingersoll—who appears earlier in Village Atheists—was Reynolds’ defense lawyer, but ultimately lost the infamous “Jersey Heresy Case” for his client. As Schmidt notes, the case stood for the following question: “whether the irreligious possessed the same civic capacities, rights, and protections as the godly.” Within this framework, the chapter covers a fair amount of biographical ground in the years leading up to the night of Reynolds’s fateful arrest, and offers much insight into the legal procedure and posturing surrounding the trial and verdict.

In the last substantive section of Village Atheists, we encounter Elmina Drake Slenker, the lone female covered with such depth. Just weeks before the verdict was reached in the Reynolds trial, Slenker (“one of the country’s most notorious atheists, an ex-Quaker and displaced Yankee”) was arrested in Virginia for both blasphemy and obscenity. The obscenity charge flowed from years of her “vast correspondence about marriage and sexuality with various editors, physicians, amateur investigators, and advice seekers” which were seen as violating the Comstock laws of the time. While awaiting federal trial, she lingered in jail until she was able to pay the “prohibitively high” bail set at $2,000—even her own husband, full of shame about his wife’s status as an atheist and her so-called obscenity, refused initially to bail her out but ultimately came forward to support his wife at trial.

Many freethinkers were hesitant to openly support Slenker to the extent her conduct and communications were being labeled and misconstrued as “obscene.” To get around the perception that they condoned so-called lewd and indecent behaviors—which were, in essence, merely medical teachings of sexual physiology and giving sex advice within a marriage—freethinkers supportive of Slenker’s mission instead rejected the idea that her work even fell within the definition of “obscene” in the first instance, thereby absolving themselves from a socially unacceptable stance.

It was a tough sell considering the evidence the postal inspectors had seized while she was under surveillance; Slenker was unafraid of using frank sexual terms in her correspondence, much less discussing contraception and preventing birth defects. The chapter also briefly but adequately covers the anti-obscenity laws set into motion by Anthony Comstock and gives the reader an idea of the kinds of constraints placed upon free speech, both religious and sexual, at the time. As Schmidt aptly notes, “[m]ale privilege and masculine presumption always remained prominent features of the infidel landscape that Slenker inhabited.” Slenker is easily seen as an ardent and tireless feminist of her time, and one I found myself rooting for the entire chapter through.

This book will undoubtedly appeal to history lovers, particularly those who enjoy biography. Schmidt is an astute and careful researcher who covers his four interesting subjects with an even hand. I question though whether this book will be off-putting and inaccessible to some; Schmidt’s prose is sometimes overwritten and overdone in ways that make it a challenging read through certain passages, and which would have benefitted from a few section headings in each chapter, especially considering the lengthy introduction to the book. Overall, Village Atheists offers a thoughtful compendium about a particularly energetic time for America’s early and vocal nonbelievers, and one that deftly fulfills an important gap in the history of some of our country’s bravest and most outspoken secularists.