What a Secular Monument Looks Like

What do war memorials look like and what do they symbolize? What shapes do they take, and whom do they represent?

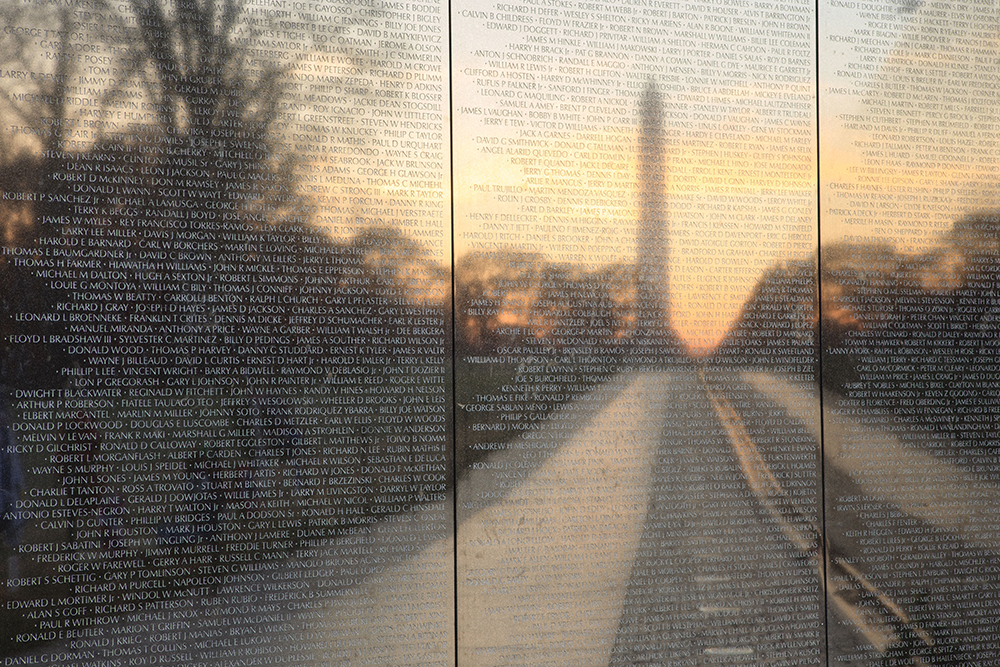

AS PHYSICAL STRUCTURES erected to celebrate armed conflicts, war memorials in the modern era more often commemorate and honor the individuals who fought and those who were injured or died in war. Memorials to American war veterans dot the entire United States in the form of statues, obelisks, arches, gardens, fountains, and other structures. National memorials, like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, honor all American service members of a conflict (over 58,000 lives lost in Vietnam). Smaller war memorials across the country highlight veterans from a certain town, commonwealth, or state, their names etched in stone, embossed on metal, or otherwise displayed for posterity.

Regardless of one’s personal position on war in general or on a specific conflict in which the United States has engaged, one can’t help but feel humbled and saddened reading the words and names on a war memorial. Often these displays include epitaphs that speak to the service, bravery, and diversity of those who made the ultimate sacrifice as members of the US Armed Forces.

In keeping with the secular nature of the United States, as guaranteed by the Constitution, the war memorials in this series honor all the individuals to whom they’re dedicated. The inscriptions may be interpretive in a poetic sense, and the architectural design may also have specific intent, often to evoke emotion, solemnity, and appreciation. But in no way do they exclude anyone on the basis of creed. As it should be, in no way is a religion incorporated into the message of these memorials.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the case with one of the war memorials in this series. It towers over a government-owned median between three major commercial/commuter roadways at the entrance to the town of Bladensburg, Maryland. Originally called the “Calvary Cross” to symbolize the crucifixion of Jesus, the Peace Cross (as it’s known today) is a forty-foot high Latin cross erected in 1925 by and with the consent of the Town of Bladensburg on prominent town-owned property in order to honor local men who died in World War I.

The plan was to erect a “mammoth cross, a likeness of the Cross of Calvary, as described in the Bible.” The cross was dedicated on July 12, 1925, at a public ceremony led by government officials and Christian clergy. The keynote speaker, Maryland Rep. Stephen Gambrill, reaffirmed the memorial’s distinctly Christian meaning, declaring: “by the token of this cross, symbolic of Calvary, let us keep fresh the memory of our boys who died for a righteous cause.”

In 1985 a bi-county commission of Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties, which had acquired the cross in 1960, spent $100,000 of taxpayer funds to renovate it. Shortly thereafter, the county commission and the Town of Bladensburg held an elaborate ceremony, replete with Christian prayers, to “rededicate” the cross to honor US veterans of all wars.

The American Humanist Association and three local residents challenged the Bladensburg cross in federal court in 2014. Two years later the AHA won its case in the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which ruled that the memorial was an unconstitutional government-sponsored edifice promoting an overriding Christian message. On February 27, 2019, the AHA will argue its case before the US Supreme Court.

The American Humanist Association and three local residents challenged the Bladensburg cross in federal court in 2014. Two years later the AHA won its case in the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which ruled that the memorial was an unconstitutional government-sponsored edifice promoting an overriding Christian message. On February 27, 2019, the AHA will argue its case before the US Supreme Court.

Defenders of the four-story Bladensburg cross have argued that when used as a war memorial, the cross is a secular symbol representing Jews, Muslims, atheists, and all other veterans. “But non-Christians are the arbiters of that question,” declares AHA Senior Counsel Monica L. Miller, who will argue the case before the Supreme Court, “and their voices leave no room for ambiguity.” Not only does the Latin cross not honor non-Christians soldiers who’ve served the United States, Miller points out, “when used as a government war memorial, the cross signifies that their sacrifices are unworthy even of mention.” War is not sacred, but service to one’s country is truly commendable. We must honor all who’ve fought and sacrificed in war with secular memorials.

The United States Marine Corps War Memorial

(near Arlington, Virginia)

This statue, dedicated in 1954, is modeled on the iconic 1945 photo taken of six US Marines atop Mt. Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima. The dates and locations of all Marine Corps battles wind around the upper part of the memorial’s base. On the opposite side of the inscription (left), is the dedication: “In Honor and Memory of the Men of the United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives to Their Country Since 10 November 1775.” While this leaves female Marines out, a number of explanatory signboards around the monument feature women Marines prominently, along with another dedication to “the Marine dead of all wars.”

The Bronx Victory Memorial

(New York City)

This memorial is dedicated to the 947 soldiers from the Bronx who died in World War I. Completed in 1932, it features a Corinthian column topped by a gilded bronze victory figure. The plaque reads: “A grateful city erected this shaft to the glorious memory of its Bronx County sons who gave their lives for their country in the World War.”

The African American Civil War Memorial

(Washington, DC)

Dedicated on July 18, 1998, the memorial features the Spirit of Freedom sculpture (soldiers on one side, a family sending their son to war on the other) surrounded by the Wall of Honor. The inscription on the sculpture’s base reads: “Civil War to Civil Rights and Beyond. This memorial is dedicated to those who served in African American units of the Union Army in the Civil War. The 209,145 names inscribed on these walls commemorate those fighters of freedom.”

World War I Memorial

(in front of Okanogan County Courthouse, Okanogan, Washington)

The base of the stone structure reads: “To the memory of the men from Okanogan County who gave their lives in the World War.”

World War I Monument in Scoville Place

(Oak Park, Illinois)

Over $50,000 was raised in 1921 for the monument, which was dedicated on Armistice Day, 1925.

The Peace Cross War Memorial

(Bladensburg, Maryland)

Originally dedicated to local men who died in WWI, since 1985 the Latin cross memorial is dedicated to all US war veterans. Since 2015 a tarp sits at the top to limit ongoing water infiltration problems.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial

(Washington, DC)

This iconic memorial occupies two acres near the National Mall and is comprised of three separate structures: the Memorial Wall, completed in 1982; the Three Soldiers bronze statue competed two years later; and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, dedicated in 1993, depicting a nurse holding a wounded soldier, a woman looking up to the sky, and another on her knees with a helmet in her hands.

This iconic memorial occupies two acres near the National Mall and is comprised of three separate structures: the Memorial Wall, completed in 1982; the Three Soldiers bronze statue competed two years later; and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, dedicated in 1993, depicting a nurse holding a wounded soldier, a woman looking up to the sky, and another on her knees with a helmet in her hands.

The architect of the first two elements, Maya Lin, has said: “I see the wall as a kind of ocean, a sea of sacrifice that is overwhelming and nearly incomprehensible in the sweep of names. I place these figures upon the shore of that sea, gazing upon it, standing vigil before it, reflecting the human face of it, the human heart.”