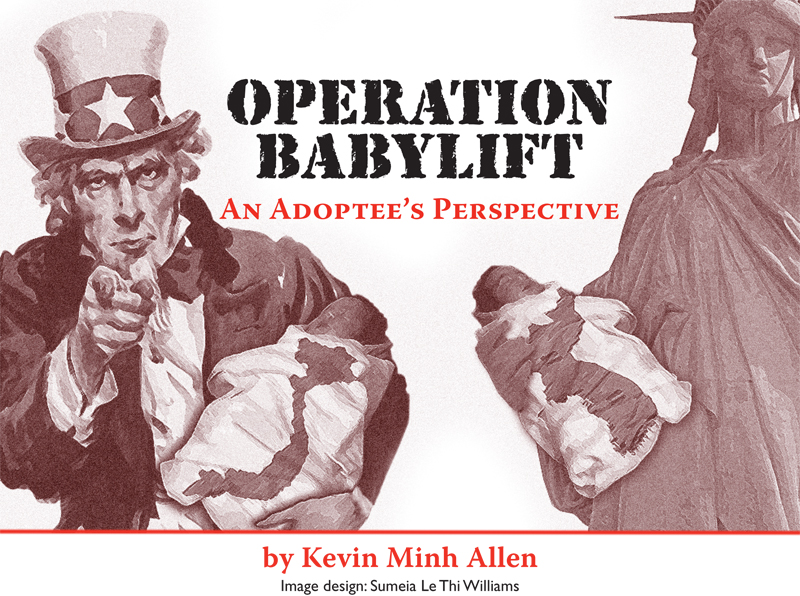

OPERATION BABY LIFT: An Adoptee’s Perspective

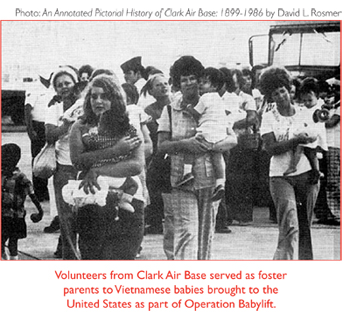

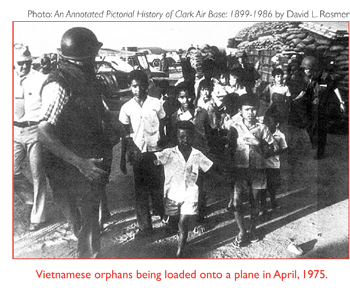

In April 1975, under the manufactured threat of a mass slaughter of infants and children by advancing North Vietnamese forces, Western relief agencies and orphanages in South Vietnam, and finally the U.S. government, pressed into action a daring “rescue” plan dubbed Operation Babylift. Vietnamese children under the jurisdiction of the relief agencies and orphanages–along with any other child who was either handed to them or picked up off the street–were to be sent out of the country and placed with adoptive parents in Western countries. The operation was controversial; aside from the fact that not all the children evacuated were orphans and adoption documentation was often sketchy, the cargo plane that lifted the initial group of evacuees crashed, killing 141 of 149 children on board. Nevertheless, by the time the Vietnam War officially ended on April 30, 1975, approximately three thousand infants and young children had been taken out of Vietnam for the purpose of adoption.

Although Operation Babylift was specific to Vietnam, it fits into a pattern of U.S. intervention in Asia that includes Korea and the adopting of Korean children in the 1950s for very similar reasons.

Cold War Calculations

After World War II, the Soviet Union and the United States attempted to divide up the world both ideologically and militarily. The Domino Theory promoted by the United States, which speculated that if a region came under the influence of communism then the surrounding countries would follow, justified using the Korean and Indochinese peninsulas as proving grounds for injecting American influence around the world. The U.S. government poured millions of dollars and thousands of combat troops and support personnel into the wars in Korea and Vietnam to preempt any more countries from falling to the communists.

After World War II, the Soviet Union and the United States attempted to divide up the world both ideologically and militarily. The Domino Theory promoted by the United States, which speculated that if a region came under the influence of communism then the surrounding countries would follow, justified using the Korean and Indochinese peninsulas as proving grounds for injecting American influence around the world. The U.S. government poured millions of dollars and thousands of combat troops and support personnel into the wars in Korea and Vietnam to preempt any more countries from falling to the communists.

A healthy dose of paternalism and ideological hegemony led to the guiding principal that the U.S. government knew what was in the best interests of the inhabitants of Korea and Vietnam. As a result, many Americans came to distrust the ability of these countries to save themselves from the scourge of communism and thus thought them incapable of self-determination.

Korean and Vietnamese children who were adopted by Americans during and after those wars were particular targets for the cold war rhetoric. In fact, it can be said that Operation Babylift and Holt International Children’s Services, which ushered in the international adoption movement, were natural outgrowths of the “better dead than Red” mentality that reduced the complexities of the world down to simple black-and-white choices.

This is the legacy that the first generation of transracial adoptees has been saddled with.

Rescue, Baptize, Christianize, and Save

In 1954, Harry and Bertha Holt, evangelical Christians from rural Oregon, found their calling when they heard about the orphaned cherubs of Korea. They had a special affinity for those children fathered by American army and civilian personnel (referred to as Amerasians). In fact, the Holts chose to adopt eight Korean children themselves. Congress even passed a special act named for the Holts, thus legalizing and legitimizing the novel practice of international adoption. Soon thereafter, the Holts inspired countless other Americans to join them in “saving” these “war waifs.” “We would ask all of you who are Christians to pray to God that He will give us the wisdom and the strength and the power to deliver his little children from the cold and misery and darkness of Korea into the warmth and love of your homes,” read a form letter sent to prospective adoptive parents.

When the 1970s came along, Americans read about Vietnamese children in the newspaper and saw them on the evening news. These children would also have the honor of being labeled charity cases and seen as more lost souls in need of saving. Churches, chapels, and ministries across the United States galvanized their congregations to collect money and materials to send to orphanages in South Vietnam, patting themselves on the back for their magnanimity at every opportunity. But many Americans didn’t just want to send in their checks and offer well wishes; they wanted to see a return on their investment. To acquire a Vietnamese child was seen as the ultimate act of selflessness and sacrifice.

The implied politicized message was that Americans were more moral than those godless communists, the Koreans and the Vietnamese, and that Americans could provide an infinitely better outcome for these castaways.

The implied politicized message was that Americans were more moral than those godless communists, the Koreans and the Vietnamese, and that Americans could provide an infinitely better outcome for these castaways.

Working hand in hand with anticommunist fervor, the Christian evangelical movement spread the assumption that the people of Asia were incapable of taking care of their own. Westerners turned their attention to the “neediest of the needy,” those children who were left to experience the aftermath of each bombardment that inevitably separated them from their families. Under the protection of the U.S. military and with the support of countless donations, these missionaries established orphanages that inadvertently took the place of indigenous methods and solutions for child welfare. With so much of the country overwhelmed by the casualties of war, ladies and gentlemen of mercy took up the mantles of healer and savior.

Since most of the major adoption agencies and child welfare organizations were funded and led by men and women of the Christian faith, they gave their extended network of families top honors in choosing suitable children for their religious households. Once their foreign charges were firmly ensconced in the family unit, the adoptive parents of numerous Vietnamese children–and of Korean children before them–set the religious tone by having them baptized with their preferred holy water. Many of us Vietnamese adoptees have acute memories of dutifully saying grace before meals and reciting the Lord’s Prayer before hopping into bed. When talking amongst ourselves, we find that many of us were not immune to the socialized rituals that had confirmed and reaffirmed our transition from heathens to blessed children in the eyes of our families and our communities.

In the context of transracial adoption, conforming to and following one’s adoptive parents’ religious practices was a mark of distinction that you were “getting along well” in your new home and “fitting in nicely.” The Bibles, the hymns, the recitations, the church camps, and especially the major national holidays had combined to become an unconscious astringent that scrubbed Korean and Vietnamese minds clean by breaking down the stains of war and orphanhood.

As many of us Vietnamese adoptees crack open and peer into yellowing photo albums, our eyes adjust to images of little brown infants swaddled in virgin white gowns, being held by a big pair of white hands for our first christening. Our eyes were either wide with fear or shut tight against the impending rush of deliverance. We turn the pages and witness ourselves chronologically fitting molds made by a mass of social and cultural forces that none of us had any control over. And now, at the end of the day, some of us will kneel down and pray for a reason, while some of us will turn to the next page in our lives and keep looking for one.

The Americans Are Coming!

In Asia, wherever the U.S. military went, prostitution and intermarriage came along for the ride. Official U.S. military policy discouraged its personnel from consorting and fraternizing with the native female population. But, the fact that thousands of mixed-race children were born to Korean and Vietnamese women tells us that regardless of the rules, human nature took over.

In Asia, wherever the U.S. military went, prostitution and intermarriage came along for the ride. Official U.S. military policy discouraged its personnel from consorting and fraternizing with the native female population. But, the fact that thousands of mixed-race children were born to Korean and Vietnamese women tells us that regardless of the rules, human nature took over.

When it came to prostitution, top U.S. brass looked the other way, while local pimps and madams carved out certain sections of the city for soldiers and civilian personnel to spend their R&R breaks. This was all done under the watchful gaze of local authorities, many of whom took a substantial cut in the proceeds. And what would a war be without rape, a crime that, for time immemorial, has been used to dominate the indigenous population and erase a proud people’s sense of self-worth?

The media portrayed the products of these unions, the Amerasians, as caged animals who were abandoned by their unfeeling mothers and missing-in-action fathers. It was as if on some level Americans feared that these children would become innocent victims of cruel and inhumane treatment by “Oriental savages.” This racist fantasy took the focus off the fact that American and other Western men had violated or cavorted with Korean and Vietnamese women, some ostensibly to teach the enemy a lesson. So, in order to soothe their conscience and fulfill a sense of obligation to those fathered by their countrymen, Americans advocated for the adoption of Amerasians. Since these children were assumed to be half American and didn’t ask to be born, it was reasoned that they should share in the benefits and good fortune of being a U.S. citizen.

It was in this way that American military intervention paved the way for private U.S. citizens to intervene in the affairs of Korean and Vietnamese families, thus establishing even more control over these nations.

Presidents, senators, congressmen, adoption agency directors, nurses, and flight attendants claim they were only trying to help us out of the mass grave that would have been our lives if they had left us in Vietnam. They’re at ease reminding us that it was they who came to our rescue while our countrymen were too busy gambling our country’s future away at the rigged roulette wheel; they’re only too happy to remind us that we were wearing rags before they picked us out of the trash heap and fit us with the rich fabric of freedom.

What they fail to mention, though, is that we were made available for adoption as a direct result of over six million tons of bombs falling over a country roughly the size of New Mexico. It was common practice to destroy villages and communities that were suspected of harboring communist sympathizers. Free-fire zones were established in which every civilian was marked for death. Agent Orange defoliated huge swaths of the countryside, and napalm and white phosphorous bombs burned skin to a crisp. Counterinsurgency protocols like the Phoenix Program were aimed at killing Viet Cong cells or their sympathizers, whoever they might be.

Our benefactors also make it a point to impress upon us how dire the situation was in the orphanages, nurseries, and hospitals, how destitute our parents were, and that we were abandoned because our mothers either loved us too much or could care less about us. What they fail to mention is that the U.S. government propped up corrupt dictatorial regimes, one after the other, that pilfered and siphoned off much foreign aid into their own coffers. Money and resources were diverted from child welfare programs into the war effort. Refugee and widow assistance was sacrificed in order to conscript, equip, and train more young men to fight for democracy.

Preposterously, our caretakers lauded American military know-how and generosity for clearing the way for scarce medical and food shipments to reach the orphanages. Individual soldiers were to be thanked for giving us their free time, bubble gum, and rides in the back of their Jeeps. Some of these soldiers even put down their guns long enough to adopt us. And, when it was time to close up shop and escape the inevitable national meltdown, military air transport was called in to ferry out the precious few, the angels of this-or-that orphanage, the “chosen ones.”

To Control the Past Is to Control the Present

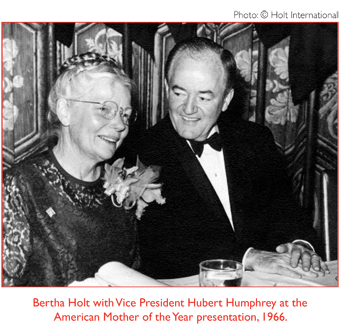

In the adoption arena, legends were made out of the names Harry and Bertha Holt and Operation Babylift because they typify many Americans’ assertions about their country’s boundless goodwill and moral superiority over its supposed “enemies.” Never mind that these legends serve to disregard factual inconsistencies, inconvenient truths, and unsatisfactory conclusions. The legacies of prominent personalities in the international adoption movement have solidified into unchallengeable testimony. Bertha Holt is characterized as a kind and pious old Christian woman who only wanted the best for the children of Korea. From proxy adoptions to Holt International Children’s Services, thousands of Korean children have been told that they have Bertha and Harry Holt to thank for breaking down racial barriers and normalizing international adoption in American society, as well as for their privileged lives today.

In the adoption arena, legends were made out of the names Harry and Bertha Holt and Operation Babylift because they typify many Americans’ assertions about their country’s boundless goodwill and moral superiority over its supposed “enemies.” Never mind that these legends serve to disregard factual inconsistencies, inconvenient truths, and unsatisfactory conclusions. The legacies of prominent personalities in the international adoption movement have solidified into unchallengeable testimony. Bertha Holt is characterized as a kind and pious old Christian woman who only wanted the best for the children of Korea. From proxy adoptions to Holt International Children’s Services, thousands of Korean children have been told that they have Bertha and Harry Holt to thank for breaking down racial barriers and normalizing international adoption in American society, as well as for their privileged lives today.

In the same vein, the protagonists of Operation Babylift are credited with saving thousands of children who otherwise would have grown up in a postwar communist dictatorship where food shortages and other deprivations would have condemned them to certain death. The Babylift was considered such a singular feel-good event that, to this day, it’s referred to as the one good thing that came out of the war.

A cottage industry involving annual commemorations and permanent memorials, as well as reunions between adoption legends and adoptees themselves, has become a fixture on the nation’s calendar. Much like legend-building, the remembrances aim to convince the participants that they represent a larger mission and purpose. There is also the implied threat to adoptees that to question the reasons and actions of one’s benefactors is to put one’s own life in question. And so Operation Babylift has become a redundant, closed-loop system of mourning, remembrance, gratitude, and redemption for an isolated, unilateral humanitarian gesture. Ironically, by remembering the operation in such a way encourages the so-called lost children of Vietnam to forget the causes and effects of the Vietnam War and leave unexamined their own adoption stories that were virtually gift-wrapped and handed to them.

Ultimately, the Holts and Operation Babylift justified the act of taking small babies from their countries of origin and raising them in a Western image by reducing the child’s circumstances to one of two alternatives: left to rot in an inhumane orphanage or raised up in a loving family where, with time and material excess, everyone would forget and be the better for it. With a mixture of good old paternalism and a pinch of racial superiority, and under cover of civil wars, social upheavals, and economic instability, they extracted us without any sense of irony that Western countries had a big hand in triggering these crises.

Praising us as Asian angels borne from cargo holds and cardboard boxes, we were never expected to look back and think about our lives before adoption, much less about our countries of birth. The American flags we were given upon assuming citizenship were supposed to blind us with star-spangled magnificence. It is only within the past decade that many of us have become wise to the racial self-hatred that had been instilled in us and have questioned the multiple loyalty tests we have been forced to take in order to prove our legitimacy in the eyes of our fellow Americans.

No More Angels For You

Vietnam is currently experiencing social and economic growing pains similar to those South Korea went through during the 1970s and 80s. Korean children were the hot commodity in international adoption up until many adult Korean adoptees put the South Korean government’s feet to the fire and made it acknowledge the mass production aspect of its adoption policies. In early 2008, the U.S. State Department investigated a growing number of inconsistencies in the documentation of children’s orphan status and reports of child trafficking. This led to a halt in adoptions between the United States and Vietnam in September. But, much like the attitude exhibited by Americans in 1975 when Operation Babylift commenced and they were criticized for seemingly taking advantage of a bad situation, many prospective American adoptive parents today are incredulous about the charges of official corruption and baby selling. These children only need a home and a loving family, they plead. Who would ever deny them that?

To this day, first-generation transracial adoptees from Korea and Vietnam are generally referred to as “war orphans” in the media and by people we encounter on a daily basis, as if it is a self-applied term of endearment. The main assumption is that we were rescued from a tragic past and handed a hopeful future, and that to look back and piece together the facts behind our orphan status would be counterproductive and even unhealthy.

Yet, this is exactly what we are doing. We dare not only to question the historical interpretations of the Korean and Vietnam Wars, but also other people’s motives and methods for transporting us out of our birth countries. The question we ask is one few people are willing, or even prepared, to answer: Who made us orphans in the first place? In order for us to have gained our second set of parents, we had to lose our first.

Yes, people can say that we were saved. But we’ll be damned if we let them have the last word.