Leading by Example: A Conversation with AHA President Rebecca Hale and Humanist Activist Todd Stiefel

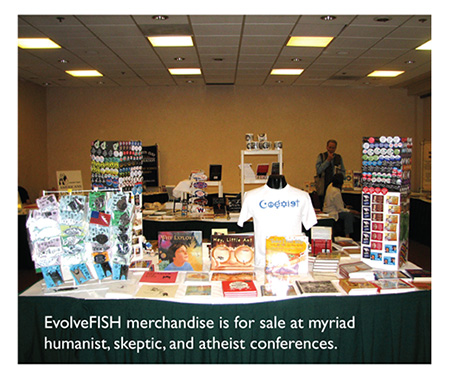

Rebecca Hale is the American Humanist Association’s twentieth president, and the fourth woman to hold that position after Suzanne Paul (1992-1993), Bette Chambers (1973-1979), and Vashti McCollum (1962-1965). Hale is the cofounder, along with her husband, Gary Betchan, of both the Freethinkers of Colorado Springs and EvolveFISH.com, the largest online seller of freethought merchandise. A long-time advocate for secularism and humanism in particular, Hale is also a certified humanist celebrant.

Todd Stiefel is founder and president of the Stiefel Freethought Foundation and is the international team captain for the Foundation Beyond Belief’s Light the Night Team benefiting the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. He serves as an advisor to a number of secular organizations, including the American Humanist Association, the Secular Student Alliance, and the Secular Coalition for America. He is also the host of the AHA podcast, The Humanist Hour.

Shortly after she was elected president in January of this year, Hale appeared on the Humanist Hour where she and Stiefel discussed fundamentalism in Colorado Springs, her split with the Unitarian church, and her plans for the AHA, including enhanced programs for young humanists. The following is adapted from their conversation.

Todd Stiefel: Congratulations on becoming the latest president of the American Humanist Association.

Rebecca Hale: Thank you, Todd. I’m thrilled to be able to direct the AHA for the next few years.

TS: What was your path to humanism? From what I understand you experienced something of a shift from Unitarianism.

RH: I never had that struggle, Todd, that so many people have confronting their hereditary religion: asking whether it made sense to them, then making the decision that it didn’t, and ultimately deciding to move on. I’m in awe of people who go through that—it seems like such a Herculean effort. I never had to do it because my parents had the good sense to bring me up in humanism. I don’t know if they were aware of the American Humanist Association per se, but they were Unitarians, and so, it’s been easy for me.

TS: The Unitarian Universalists (UUs) have indeed moved in a more theistic direction. Do you have any thoughts on how we as a humanist movement might be able to help nudge the UUs back towards humanism?

RH: I was raised in the Unitarian church during a time when it was, I’d say, 90 percent humanist. What happened essentially was that the Unitarian movement moved away from me. UUs opened their doors to people who were exploring all different kinds of faith traditions, which I thought was appropriate. But I think they became a little bit too mercenary. They were worrying about losing memberships and waning congregations, so they decided to try to be all things to all people. The so-called soft Christians got into a power position because, I believe, the UUs felt they had the larger market, and they wanted to go after those Christians. Humanists became expendable.

My husband Gary and I had grown our local freethought group to about 200 people, and I was looking to bring the group under the tent of the Unitarian church because I was still feeling some loyalties to them and I wanted the two groups to be more symbiotic. But I actually had a UU minister say to me, “Well of course, Becky, you’re welcome. But I can’t imagine why an atheist would want to be here.”

TS: Ouch.

TS: Ouch.

RH: I do understand that there are Unitarian congregations in other parts of the country that are holding on tightly to their humanist roots, and they are probably the best avenue in. It might also be that other Unitarians will look around at the “nones” and say, “Oh, those humanist types are our market. We need to get them back.”

TS: I sometimes wonder if we should just start showing up, en masse, at UU services one week, and then let’s all not show up the next week and help show them our numbers.

RH: That’s a great idea. You know, each Unitarian Universalist church is owned by its community, not by the UU headquarters in Boston. So, churches go with the flavor of their congregations and the flavor of their ministers. The other piece of it would be to utilize seminary schools, where it’s important to have a stronger humanist influence.

TS: You’ve certainly taken on a pretty significant leadership role in the larger freethought movement. What drove you to that level of passion?

RH: I live in Colorado Springs. Need I say more? But seriously, I had been on the board of directors at our local Unitarian church, and I’d also taken a spin working with the youth of that church for three or four years. Then Gary took over just as Focus on the Family was moving to Colorado Springs, and there was a big push by Ted Haggard to move his New Life Church out of his basement and into a big facility as well.

Along with all of this came a young lady who was in Gary’s high school group. She was a swimmer whose team would pray before getting into the water at meets. This bothered her enough that she finally asked her coach, “Would you mind if I didn’t come out of the locker room until after the prayer?” He said, “Of course,” and she thought everything was fine, but she never got off the bench again. She wasn’t in the water swimming anymore because the coach told her she wasn’t a team player. Around the same time, an amendment passed the Colorado state legislature preventing any use of “protected class” legislation for gays and lesbians, which, among other things, would have left them vulnerable to discrimination in housing and employment. (I’m happy to say it was later found to be unconstitutional.)

So all of these things were going on, this was around 1993, and Gary and I looked at each other and said, “We need to stir this pot up a little bit and get a dialogue going.” At the same time, the Independent newspaper had just been established in Colorado Springs and we wanted to support it by purchasing an ad. We both had salaried jobs, so we really didn’t have a product or service to advertise. But we’d noticed the Darwin fish emblem on the backs of cars, and we thought, “Let’s advertise to sell the Darwin fish.” And we set about doing that, I think it was in October. On Christmas Eve of that year we were driving around town in the snow and the ice, delivering little Darwin fish magnets, Darwin fish coffee cups, and stuff like that to people.

I’ve always been a little bit counter-culture, but it was really the repressive attitude of the Christian fundamentalists and evangelicals in Colorado Springs that pushed me to be more passionate about this cause. They weren’t teaching evolution in biology classes in the northern school districts, they were teaching creation science. This was our response and I’m so happy we did it.

TS: What’s it like for you, on a day-to-day basis, living in Colorado Springs with some relatively fundamentalist people and, in particular, their influence on the Air Force Academy?

RH: We were aware of the religious pressure on the cadets for quite a few years before it got any press. Cadets attended some of the freethinker meetings, and they’d tell us they had to say they were going to a church meeting or a Bible study to get permission to go off base. One of the gals who works for EvolveFISH actually ended up marrying one of the early members of the freethinkers group at the Air Force Academy. And some of our members are AFA instructors who are sponsoring the group up there and working with them. So, it’s the kind of thing we’ve kept an eye on, we’ve reached out from time to time.

RH: We were aware of the religious pressure on the cadets for quite a few years before it got any press. Cadets attended some of the freethinker meetings, and they’d tell us they had to say they were going to a church meeting or a Bible study to get permission to go off base. One of the gals who works for EvolveFISH actually ended up marrying one of the early members of the freethinkers group at the Air Force Academy. And some of our members are AFA instructors who are sponsoring the group up there and working with them. So, it’s the kind of thing we’ve kept an eye on, we’ve reached out from time to time.

The influence of fundamentalism hasn’t been so much from the academy out to the Colorado Springs community as it has been the other way around. The Christian fundamentalists have had unprecedented access to cadets—into the dormitories, into all the social halls. They’ve had offices at the academy, cadets have been given special privileges if they participate in the evangelical programs, and so on.

For lots of reasons, I think of Colorado Springs as a strange community. As I’ve traveled around the country, I’ve become more and more aware of just how out of the norm we are.

TS: It seems like the whole state of Colorado is an unusual blend of really progressive and really conservative people. Kind of a strange dichotomy.

RH: Indeed it’s a very conflicted, schizophrenic state. Part of it is that Coloradoans fancy themselves libertarians, and that’s where a good percentage of the support for the marijuana laws comes from. The libertarian component of the Republican Party has joined with progressives and the Democrats to get some of those liberal issues through. But when you pull in a religious position, say, on reproductive choice or the environment, they lose their libertarian leanings and they vote right-wing Republican.

TS: Let’s talk about the American Humanist Association a bit. What new directions would you like to take the AHA in now that you’re the president?

RH: Everybody asks me that. I think the AHA has been doing really good work. I’ve been very impressed by the Kids Without God project and website, and that woke me up to the potential of us putting larger emphasis on programming for children, and youth especially. When I was in the Unitarian church as a child, and as a student in middle school and high school, I was very involved in what was then called the Liberal Religious Youth (LRY) program. It really did sustain me growing up in Colorado Springs. So I would like to see the AHA get more involved in supporting our membership around the country in creating programming for children and youth.

Sometimes I’m afraid that we’re getting our fingers into too many pies, or that there’s only so much human energy that can go into this. But our youth are so very important.

The American Humanist Association has progressive, ethical positions on sex education, the environment, and so on. But what I’ve seen with some people outside the movement, and even some within the movement, is that in raising children they say, “Oh, well, my parents forced that religion on me and I don’t want to force my religion or my life philosophy on my kids. I want them to find their own way.” To me, that’s an abdication of parental responsibility. I don’t feel that we need to force these things on our children, and I’ve been careful not to do that with my kids. I let them know where I stand, I provide them with opportunities, with education, and I allow them to explore. But if a child doesn’t know where the parent stands, they’re lost and they become vulnerable to the people who will prey upon them.

TS: I think you’re totally right. I’ve heard Dale McGowan [author of Parenting Beyond Belief] talk about parenting in this regard as an inoculation, like exposing people to a weakened form of a disease to give them a degree of immunity. And if you shield your children from religion, they’re not inoculated. I’m paraphrasing maybe a little more aggressively than he does, but, frankly, kids are more easily preyed upon if they’re in the dark. I agree that it’s important to let your kids know where you stand, but it’s also good to expose them to a lot of other ideas and let them make up their own minds. Don’t hide things from them, because if they’ve never heard of the concept of “happy forever after in heaven” until they hear it from someone else, it could be a problem; it could be something that ends up with more influence than it necessarily should.

RH: If you study the very conservative religions, they don’t want children to have time to contemplate and process. They don’t want anybody to have the time. People can think about what color car they’re going to buy or how they’re going to paint their house or what clothes they’re going to put on in the morning, but they don’t want people to critically analyze their belief structures. Critical thinking doesn’t work for conservative religions.

TS: What advice would you give to members of the AHA, let’s say, or other humanists in terms of what they can do to get involved and help promote the humanist movement?

RH: Number one is you have to join, right? You don’t necessarily have to go public—you know, people can lose jobs, and we don’t want our folks being unemployed or otherwise disenfranchised. But join the organization—and support it financially, if you’re in the position to. If you’re not, support it with the way that you live, support it with the way that you vote, support it by volunteering at schools and keeping your eyes and your ears open for church-state violations, and then quietly feed that information back to the American Humanist Association.

Meet with other humanists, because a sense of community is very empowering. Meet-ups are easy to put together and require very little commitment. We need to speak out where it’s safe and where we feel that we won’t be damaged by it; we need to speak up and say, “You know, maybe it’s okay to not believe in that God. Maybe it’s okay to let women have choice. Maybe it’s okay for our science teachers to teach evolution.”

Meet with other humanists, because a sense of community is very empowering. Meet-ups are easy to put together and require very little commitment. We need to speak out where it’s safe and where we feel that we won’t be damaged by it; we need to speak up and say, “You know, maybe it’s okay to not believe in that God. Maybe it’s okay to let women have choice. Maybe it’s okay for our science teachers to teach evolution.”

TS: Project yourself into the future for a moment: when your term as AHA president is over, what do you want to look back on with satisfaction?

RH: Well, I’d like to look back on an organization that has doubled, tripled, or quadrupled in size—an organization that doesn’t have to go to Washington, DC, begging them to take our perspective into consideration when they make laws. I’d like it to be understood that secular people can be moral, ethical, and valuable contributors to the culture. And I’d like there to be a robust program for youth. Just as we have local groups for adults, I’d like us to have local groups for young people. The program doesn’t have to be fancy, just mainstream.

TS: I would’ve loved to have that kind of resource when I was young. I remember my mom suggesting I go to the local church youth group to make friends, meet girls, things like that. It would’ve been nice to have a secular alternative.

RH: As I said earlier, it was invaluable to me. There are skills you learn when you’re involved in a youth group that you don’t get in school.

One thing I’d like to do, either in collaboration with Planned Parenthood or all on our own, is to provide an information-based sex education program for our communities. I think it’s so important for kids to really know what their options are. And not just physiology. Some of these programs are so clinical they lose sight that there are some emotional and chemical things that happen in relationships, and those are things that you have to deal with. So, I think a really fleshed-out, scientifically based sex education program that we could offer up to the secular world would be very valuable.

TS: And it would be valuable to non-secular people as well, because a lot of that information isn’t readily available in an unbiased format.

RH: No, it isn’t. Years ago my son was in a program offered by the Unitarians, which I think they’ve since disbanded because it got some bad publicity. It was called “About Your Sexuality,” and it included the most practical homework. For one, you had to buy a condom. It was those kinds of things that break the ice, and sure, it was scary.

TS: It was scary the first time I did it.

RH: My family and I were up in one of the little mountain towns outside of Colorado Springs where we’d gone to cut down a Solstice tree. We stopped at a convenience store and my son went in to use the bathroom and he came out and he said, “Can I have some change? There’s a condom machine in there—I can do my homework!” The program also got kids into a maternity birthing center where they all had to get up on the table—boys and girls—and put their feet in the stirrups and see all the equipment. Of course they were always dressed. It was an educational experience for him that was useful and practical, and it didn’t rely on having to pretend that there were no instincts in his body. It made sense. So, I’m after practical stuff that we can employ.

TS: Is there anything you’d like to add before we sign off?

RH: There is one thing I’d like to mention: the people. The people I’ve met in the secular movement, and especially in the humanist movement, are amazing and I am always so very grateful that I get to hang out with people of this caliber. I get to hang out with the Todd Stiefels and the Neil deGrasse Tysons—

TS: You did not just lump me in that same sentence. You just insulted poor Neil.

RH: Oh, no, I didn’t. Richard Dawkins is another, and Daniel Dennett. But the point I’d like to make is that it’s not just the famous people. It’s the people I sit down in casual conversation with at a convention or at a meeting. The way their minds work and the humanity and the caring that I see in these individuals gives me hope for the world.

TS: Well, r’amen* to that. And I want to just say thanks on behalf of the American Humanist Association for volunteering your time to be the president of the organization. I know it’ll all be a big commitment, and it’s appreciated.

RH: Thanks. It’s much bigger than they told me it was going to be.

TS: Fooled you!

RH: Truthfully, I’m honored and I’m looking forward to it. It’s going to be an interesting ride.![]()

*From the Wikipedia entry on the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster: “R’amen” is a parodic portmanteau of the ecclesiastical term “Amen” and “ramen” referring to instant noodles.