No School Breaks The Ongoing Struggle to Preserve Secularism in Education

Ever think we’re finally approaching a clear understanding of the establishment clause of the U.S. Constitution? Think again. Every week seems to bring a fresh controversy about the separation of church and state in public life, whether it be a public memorial featuring a cross or a Christian prayer said before a city council meeting. Religion is seeping into the public education system as well, with legislators finding ways to introduce biblical ideas into public school courses or funnel public money to parochial schools through voucher programs.

In a major win for school voucher advocates, the Indiana Supreme Court on March 26 upheld the state’s school voucher program, which allows low- and middle-income families to send their children to private and parochial schools using public money. As the New York Times reported, the majority of approximately 9,000 families that have enrolled since the law passed in 2011 have selected schools with a religious affiliation for their children. That’s because the majority of approved private schools are parochial, a statistic not unique to Indiana.

Voucher programs have long raised questions about the separation of church and state, namely whether taxpayer money should be used to fund religious schools that are not subject to government oversight. In 2002 the U.S. Supreme Court declared Ohio’s school voucher program, where the majority of public money was used to enroll students in parochial schools, constitutional in a 5-4 ruling. Writing for the conservative majority in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist said the “Ohio program is entirely neutral with respect to religion” and “permits . . . individuals to exercise genuine choice among options public and private, secular and religious.” Many groups, including the ACLU, disagreed with the ruling as the so-called “genuine choice” provided by school vouchers is usually limited to religious schools.

Voucher programs have long raised questions about the separation of church and state, namely whether taxpayer money should be used to fund religious schools that are not subject to government oversight. In 2002 the U.S. Supreme Court declared Ohio’s school voucher program, where the majority of public money was used to enroll students in parochial schools, constitutional in a 5-4 ruling. Writing for the conservative majority in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist said the “Ohio program is entirely neutral with respect to religion” and “permits . . . individuals to exercise genuine choice among options public and private, secular and religious.” Many groups, including the ACLU, disagreed with the ruling as the so-called “genuine choice” provided by school vouchers is usually limited to religious schools.

Twelve states and the District of Columbia currently offer voucher programs, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. The Louisiana Supreme Court recently heard an appeal about the state’s voucher program, after a lower judge ruled part of its financing plan unconstitutional in December. The state’s Supreme Court had yet to issue a ruling at the time of this writing.

On the federal level, Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) and Senator Lamar Alexander (R-TN) recently proposed a budget amendment to allocate $14.5 billion in Title 1 funds—reserved for public schools and districts that serve a high percentage of low-income students—for 11 million students to use at public or private schools of their families’ choice. (President Barack Obama is opposed to a federally funded voucher program.) Currently, the District of Columbia’s voucher program is the only one in the nation that receives federal funds.

Humanists have long opposed voucher programs because they create inequality, divert much needed funds from the public school system, and threaten religious liberty.

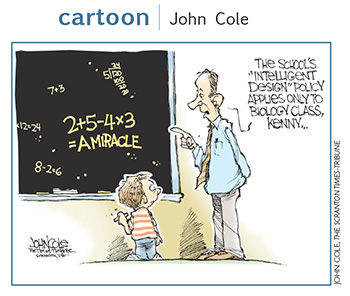

The issue of religious instruction creeping into science classes in U.S. public schools is another issue that just won’t go away, with many states still trying to give creationism a place at the table next to evolution.

There’s a renewed effort underway in Louisiana to repeal the state’s Science Education Act which, according to the law, was passed in 2008 to “promote critical thinking skills, logical analysis, and open and objective discussion of scientific theories being studied including evolution, the origins of life, global warming, and human cloning.” Critics, led publicly by teen activist Zack Kopplin, say the law allows for teaching creationism and intelligent design, as well as the undermining of theories agreed upon by scientific consensus, in public schools.

Louisiana Senator Karen Carter Peterson (D) pre-filed the bill to repeal the law in mid-March, an effort supported by seventy-eight Nobel laureates in the sciences and many organizations including the National Association of Biology Teachers and the Louisiana Coalition for Science, according to the National Science Education Center.

Similar pieces of science education legislation were introduced in other states, including Oklahoma, Arizona, Colorado, Montana, and Indiana, but all failed to make it out of committee. Still alive is a Missouri House bill that would require “textbooks covering any scientific theory of biological origin [to] devote equal treatment to evolution and intelligent design.”

While the fight over science curriculum rages on, other states have found ways to teach the Bible in public schools by creating elective Bible courses. Six states—Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and South Carolina—currently have legalized such elective courses in high schools. In an effort to become the seventh state in this group, the Arkansas House overwhelmingly passed a bill in February to create an “academic” elective Bible study course. The bill was last referred to a Senate committee.

While the fight over science curriculum rages on, other states have found ways to teach the Bible in public schools by creating elective Bible courses. Six states—Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and South Carolina—currently have legalized such elective courses in high schools. In an effort to become the seventh state in this group, the Arkansas House overwhelmingly passed a bill in February to create an “academic” elective Bible study course. The bill was last referred to a Senate committee.

In March, a bill was filed in the North Carolina Senate proposing a high school elective course that would cover the Bible’s Old Testament, New Testament, or a combination of both. According to the bill, the class must maintain “religious neutrality and [accommodate] the diverse religious views, traditions, and perspectives of the students . . . and not endorse, favor or promote, or disfavor or show hostility toward any particular religion, nonreligious faith, or religious perspective.” The problem, of course, is enforcing this very important part of the bill.

The Texas Freedom Foundation released a report this year detailing the failures of that state’s elective Bible courses, which were enacted by the legislature in 2007. In various cases, the group found that the course reflected the teacher’s own religious bias, included curriculum about young Earth creationism, or taught information that was simply incorrect.

2013 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court decision in Abington School District v. Schempp in which public school-sponsored prayer or mandatory Bible readings were found unconstitutional. Religious freedom advocates have been working to maintain the separation of church and state in U.S. schools and government educational programs ever since. Something tells me the next fifty years will require just as much vigilance.![]()

Sarah Anne Hughes graduated from American University and works as the communications assistant for the American Humanist Association.