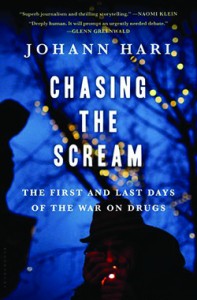

Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs

Whether someone becomes addicted to drugs has much more to do with their childhood and their quality of life than with the drug they use or with anything in their genes. This is one of the more startling of the many revelations in the best book I’ve read so far this year: Johann Hari’s Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs.

We’ve all been handed a myth. The myth goes like this: certain drugs are so powerful that if you use them enough they will take over and drive you to continue using them. It turns out this is mostly false. For example, of people who have tried crack in their lives, only 3 percent have used it in the past month and only 20 percent were ever addicted. U.S. hospitals prescribe extremely powerful opiates for pain every day, and often for long periods of time, without producing addiction. When Vancouver blocked all heroin from entering the city so successfully that the “heroin” being sold had zero actual heroin in it, the addicts’ behavior didn’t change. In other words, they kept using the fake drug at the same rate. Some 20 percent of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam were addicted to heroin, but when they got home 95 percent of them simply stopped using within a year. (So did the Vietnamese water buffalo population, which had started eating opium during the war.) The other 5 percent of soldiers who continued using had either been addicts before they went to war and/or shared the trait most common to all addicts (including gambling addicts): an unstable or traumatic childhood.

Most people (90 percent according to the United Nations) who use drugs never get addicted, no matter the drug, and most who do get addicted can lead normal lives when the drug is available to them. And even then it’s possible for them to gradually stop using it.

But, wait just a minute. Scientists have proven that drugs are addictive, haven’t they?

It’s certainly been shown that a rat in a cage with absolutely nothing else in its life will choose to consume huge quantities of drugs. So, if you can make your life resemble that of a caged rat, the scientists will be vindicated. But if you give a rat a natural place to live with other rats to do happy things with, experiments referred to in Chasing the Scream show the rat will ignore a tempting pile of “addictive” drugs.

And so will you. And so will most people. Or you’ll use it in moderation. Before the War on Drugs began in 1914 (a U.S. substitute for World War I?), people bought bottles of morphine syrup and wine and soft drinks laced with cocaine. Most never got addicted, and three-quarters of addicts held steady, respectable jobs.

Is there a lesson here about not trusting scientists? Should we throw out all evidence of climate chaos? Should we dump all our vaccines into Boston Harbor? Actually, no. But there is a lesson here that’s as old as history: follow the money.

Drug research is funded by a federal government that censors its own reports when they come to the same conclusions as Chasing the Scream. When it comes to drugs, the federal government only funds research that leaves its myths in place. Climate deniers and vaccine deniers should be listened to. We should always have open minds. But thus far they don’t seem to be pushing better science that can’t find funding. Rather, they’re trying to replace current beliefs with beliefs that have less basis behind them. Conversely, reforming our thinking on addiction actually requires looking at the evidence being produced by dissident scientists and reformist governments, and the evidence from these sources is pretty overwhelming.

So where does this leave our attitudes toward addicts? First we were supposed to condemn them. Then we were supposed to excuse them for having a bad gene. Now we’re supposed to feel sorry for them because they carry horrors within them that they cannot face, and in most cases they’ve carried them since childhood? There’s a tendency to view the “gene” explanation as the more believable excuse. If 100 people drink alcohol and one of them has a gene that makes him unable to ever stop, it’s hard to blame him for that. How could he have known?

But what about this situation: Of 100 people, one of them has been suffering in agony for years, in part as a result of never having experienced love as a baby. That one person later becomes addicted to a drug, but that addiction is only a symptom of the real problem. Now, of course, it is utterly perverse to be inquiring into someone’s brain chemistry or background before we determine whether or not to show them compassion. But I have a bit of compassion even for people who cannot resist acting in such a nonsensical manner, and so I appeal to them now: Shouldn’t we be kind to people who suffer from childhood trauma? Especially when prison makes their problem worse?

But what if we were to carry this beyond addiction to other undesirable behaviors? There are other books presenting strong cases that violence, including sexual violence and suicide, have in very large part similar origins to those Hari finds for addiction. Of course violence must be prevented, not indulged. But the best way to reduce violence is to improve people’s lives—to improve not only the current lives of addicts but also the lives of young people at risk. Bit by bit, as we have stopped labeling people of various races, ethnicities, gender identifications, sexual orientations, and disabilities as worthless, and as we begin to accept that addiction is a temporary and non-threatening behavior rather than the permanent state of a lesser creature known as “the addict,” we may move on to discarding other theories of permanence and genetic determination, including those related to violent criminals. Someday we may even outgrow the idea that war or greed or the automobile is the inevitable outcome of our genes.

Sadly, blaming everything on drugs, just like taking drugs, seems much easier.