What Consent Means and How to Teach It

The #MeToo and Time’s Up movements have highlighted how too many men have harassed or assaulted women—and men—through-out the decades and across many professions. Most attention has been focused on analyzing incidents and discussing appropriate consequences. But what about preventing further events? One of the best ways to do that is by educating people—boy, girls, men, and women—about the importance of consent and how it works. We may assume that respect is obvious, but it needs to be taught, emphasized, and demonstrated.

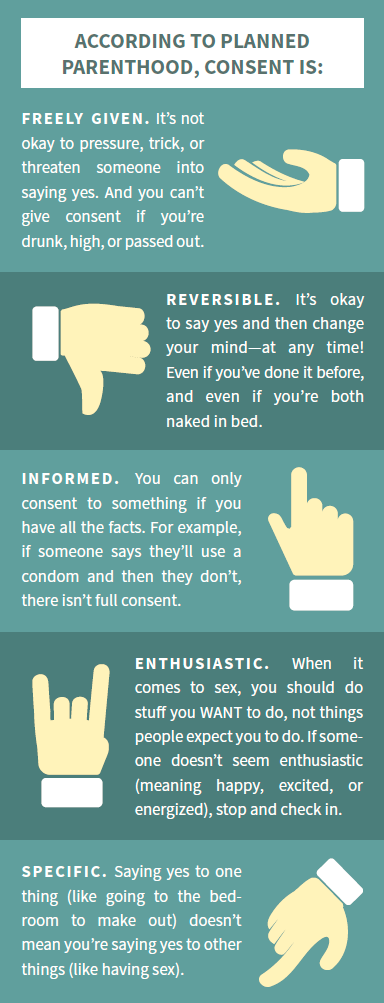

Consent is about giving permission or approval and applies to much more than sex. It’s about communicating what contact is wanted and unwanted, understanding where one’s boundaries are, and recognizing that each person has the right to make their own decisions, especially decisions concerning their body. “No means no” assumes the default is “go ahead” unless stopped, and it puts the onus on the people who are feeling uncomfortable to speak up to the people making them uncomfortable. We should instead teach “yes means yes,” making both parties responsible for expressing consent and understanding what consent entails. The Planned Parenthood website explains that consent is freely given (not pressured), reversible (can change or be taken away), informed (agreed upon), enthusiastic (enjoyable), and specific (not all encompassing).

Opponents of comprehensive sex education programs—particularly Planned Parenthood’s Get Real program taught in thirty-one states—argue that it teaches “too much too soon,” that informing students how to have safe sex encourages them to be sexually active. However, medically accurate, age-appropriate curriculum has shown to delay sex and improve communication skills for healthy relationships. In January 2018, UNESCO updated its International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education—originally developed in 2009—to include a focus on respect for human rights and gender equality. It outlines curriculum for ages five and up on consent, privacy, and bodily integrity and includes details on the right to decide who can touch your body, understanding unwanted sexual attention, and being in control of what you will or will not do sexually.

Abstinence-only programs are incomplete, inaccurate, and dangerous but are still strongly supported by leading politicians. This includes President Donald Trump, who has cut funding to comprehensive sexual education programs. A recent analysis in Teen Vogue, citing a 2004 US House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform report, notes that “federally funded abstinence-only programs reinforce gender stereotypes about female passivity and male aggressiveness,” which often correlate with intimate partner violence. These programs fail to address contraception, safe-sex practices, sexual orientation, sexually transmitted infections, affirmative consent, and healthy relationships. If we don’t educate students on their options and how to communicate with partners, we’re robbing them of the ability to make decisions for themselves and the knowledge to implement those decisions. Teachers have had to come up with creative ways to teach about protection, like the teacher in Mississippi who was prohibited from showing students how to put on a condom and so instead demonstrated how to roll a sock onto their foot in order to protect their feet with “correct and consistent sock use.” Likewise, illustrators have found clever ways to describe how simple consent can be.

Only twenty-four states require that public schools teach sex education, but awareness of the need for consent education is growing. Missouri is working on a bill that would require statewide sex education to include discussion on consent, sexual assault, and violence for middle and high schools. Rhode Island has received bipartisan support on a bill that would allow consent in secondary schools, while Oklahoma is moving forward with Lauren’s Law (Bill 2734) to create age-appropriate programs in Oklahoma schools about relationship issues, sexual assault, and consent. Tufts University in Massachusetts held its first annual Sex Health Week earlier this year to bring needed dialogue on consent and relationships to campus, and the University of Maryland held an event in March called “Let’s Talk About Sex” to address how sexual assault and violence affect survivors and how we can prevent violence by building healthy relationships.

While these efforts are welcome, consent education must start at home even before children enter school. “The lessons girls learn when they’re young about setting physical boundaries and expecting them to be respected last a lifetime, and can influence how [a girl] feels about herself and her body as she gets older,” explained Dr. Andrea Bastiani Archibald in a November 2017 post reminding parents not to force their daughters to hug family, even during the holidays. The developmental psychologist and the chief girl and parent expert at Girls Scouts of the USA added: “sadly, we know that some adults prey on children, and teaching your daughter about consent early on can help her understand her rights, know when lines are being crossed, and when to go to you for help.” There are many ways to show appreciation other than hugs and kisses, and wanted touch is more enjoyable for all.

As has been well documented, it isn’t just young girls who are pushed to give people hugs and kisses. Remember the infamous Trump Access Hollywood video? Billy Bush says to Arianne Zucker, “How about a little hug for the Donald? He just got off the bus.” These words are especially disgusting knowing the “locker room talk” that had occurred only moments before on that bus.

Last year actor David Schwimmer produced a series of sexual harassment PSAs with director Sigal Avin to show how predatory men often take advantage of power struggles in the workplace. The videos—each under ten minutes—show exactly how awful and unsettling real life experiences can be and why it’s difficult for victims to speak up. The public sharing of stories like these has forced men to re-evaluate how they treat women. When men joke that “no means yes and yes means harder” or when a fraternity chants and puts up banners saying “no means yes and yes means anal,” and when accusers are being attacked more than listened to, can we really be shocked that the #MeToo movement has grown so rapidly? Inspired by #MeToo, Schwimmer and fellow actor David Arquette launched a campaign in March called #AskMoreOfHim, focusing on men’s obligation to get more involved in tackling abusive behavior of men in powerful positions towards women.

Fortunately, the growth of #MeToo has also inspired the spread of more accurate information about sex and healthy relationships online. In February the Guardian profiled five women from around the world who are creating apps and new technologies to educate communities on sexual health. They connect children to doctors, counselors, and teachers so that all can receive correct information and have their questions answered no matter where they live. With proper consent education we can all work to prevent future sexual assault, harassment, and violence.