iFantasyAre Tech Giants Monopolizing the Future?

In August a federal grand jury in San Jose, California, found that Samsung Electronics Co. had infringed on six patents owned by Apple Inc. Meanwhile, the jury rejected the counter-claims that Apple had violated Samsung’s intellectual property and recommended that Apple be awarded $1.05 billion in damages. It is the third largest award in the history of U.S. patent litigation, a figure that could possibly increase depending on the district court judge’s evaluation of the jury’s findings. The violated patents ranged from design issues to interactive characteristics of Apple’s operating system used in the iPod touch, iPad 2, and the iPhone 3G, 3GS, and iPhone 4.

In August a federal grand jury in San Jose, California, found that Samsung Electronics Co. had infringed on six patents owned by Apple Inc. Meanwhile, the jury rejected the counter-claims that Apple had violated Samsung’s intellectual property and recommended that Apple be awarded $1.05 billion in damages. It is the third largest award in the history of U.S. patent litigation, a figure that could possibly increase depending on the district court judge’s evaluation of the jury’s findings. The violated patents ranged from design issues to interactive characteristics of Apple’s operating system used in the iPod touch, iPad 2, and the iPhone 3G, 3GS, and iPhone 4.

The fact that several legal rulings outside the United States have viewed Samsung’s case more favorably—most recently in the U.K. and Japan—illustrates the complexity of the issues at stake. The ensuing critical debate in the aftermath of the San Jose court battle raised questions about the qualifications of the nine-member jury whose decision came much sooner than anyone had expected. Most critics, however, point fingers at what they view as a malfunctioning patent system in the context of today’s high-speed technological development—where everyone appears to be building on others’ ideas. Richard Posner, one of the most respected judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals, recently opined that patent trials of this kind ought to have been resolved in the Patent and Trademark Office, not in federal court. Legal scholar Robin Feldman argues that Apple’s patent rights should never have been granted in the first place, since they stifle innovation and leave the consumer in a worse situation.

Commentators, bloggers, and consumers tend to see the dispute as one that involves either a principle of originality, or, conversely, principles of creativity and free consumer choice. While some argue that Samsung is willfully copying Apple’s painstakingly designed product identity, others suggest that Apple’s legal strategy is simply a way to avoid competing openly in the marketplace. And the drawn-out fight between two of the world’s biggest electronics companies isn’t over. Samsung vows to appeal the verdict, while Apple has already filed claims against other Samsung products that allegedly infringe the company’s patent rights.

Underneath this prolonged legal saga, there is a different set of issues that have barely been addressed in the current debate, which has focused on narrow technicalities and bureaucratic trivialities and has ignored a deeper narrative. In truth, the legal debate about who owns the right to produce rounded square icons or various zoom functions is merely a way of distracting our attention from an endlessly more worrying issue, namely the technological monopolization of the future.

Under the visionary leadership of Steve Jobs, Apple made an incredible comeback in the late 1990s with the official launch of iMac and the 1997 “Think Different” ad campaign. The spoken message of that ad is worth reproducing: “Here’s to the crazy ones. The rebels. The troublemakers. The ones who see things differently. While some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.” The voice-over—accompanying images of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Amelia Earhart, and Albert Einstein—had a clear message: the future belongs to those who are brave enough to risk changing it.

Technology has always held up the alluring promise of self-control, the ability to master one’s own fate and define the future. The more technologically advanced we are—so the fantasy goes—the more control we have over the contingencies of nature. What essentially defined the late twentieth century was the wild acceleration of this basic fantasy into ever more excessive, private forms, a development that has hardly abated since. During the ’90s, as the world went online—or, as the world disappeared into people’s private spaces—technology intertwined with the everyday lives of individuals to a degree that only a few decades earlier would have seemed like pure science fiction. It’s easy to forget or trivialize the enormous implications of this massive technological revolution—one that tore apart old empires and turned traditional hierarchies upside-down—because we’re essentially still in the midst of it and, instinctively, we know we ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

Apple, perhaps more than any other company, took advantage of this fin de siècle fantasy. It found a way to give voice to a “crazy” consumer desire empowered by radically new technological advancements: a desire to think differently, to seize the future, to design one’s own life—all with the help of Apple products. Before Apple, the technological gadget was primarily perceived as an external object, like the yellow Sony Walkman of the 1980s. The iPod, iPhone, and the iPad all brought us one step closer to an actual bridging of the gap between subject and object.

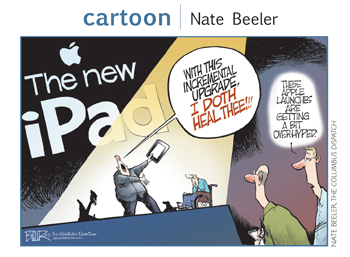

That such “iGadgets” have evidently failed to attain anything remotely close to an actual unity of subject and object—the old philosophical aim of overcoming that which alienates us from nature—is a secondary issue, one that is forever anticipated through the concept of the annual product and software upgrading. The iPod was, after all, just another MP3 player, perhaps a tad more fancy looking. On the other hand, it was much more than that; inherently, the iPod promised a lot more than what was technologically possible at the time—that is to say, it always anticipated the iPhone, the iPad, and all the products yet to come. The iPod was, in other words, a promise, a sublime fantasy that lured us into believing that the future lay at our fingertips.

That such “iGadgets” have evidently failed to attain anything remotely close to an actual unity of subject and object—the old philosophical aim of overcoming that which alienates us from nature—is a secondary issue, one that is forever anticipated through the concept of the annual product and software upgrading. The iPod was, after all, just another MP3 player, perhaps a tad more fancy looking. On the other hand, it was much more than that; inherently, the iPod promised a lot more than what was technologically possible at the time—that is to say, it always anticipated the iPhone, the iPad, and all the products yet to come. The iPod was, in other words, a promise, a sublime fantasy that lured us into believing that the future lay at our fingertips.

As for what’s at our fingertips, one needs to think no further ahead than to the omnipresence of the application, or app, surely the soul of any iGadget. With its app store, Apple established a system that encouraged users to design ingenious solutions to everything—and more. The store at present contains over 500,000 apps ranging in categories from business, travel, news, social networking, entertainment, education, family, sports, fitness, games, music, art, and lifestyle. But regardless of quantity, the seed of a brave new world was planted—that is, the prospect of a future already structured, mapped, decoded, subtitled, interpreted, and re-routed for us. That this world has been drained of surprises, doubt, wrong answers, and false routes is perhaps an inevitable by-product of a fantasy taken to its extreme—but surely not a problem an app might solve, perhaps an app that encourages us to “think different.”

This leads us back to the question: What’s really at stake in the ongoing legal twist between tech giants Apple and Samsung?

One of Samsung’s more bizarre arguments against Apple’s lawsuit was that the rectangular iPad shape with rounded corners had in fact been anticipated by Stanley Kubrick in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey in which astronauts casually use tablet-like devices while eating. It’s tempting to suggest that the full extent of the absurdity of this argument is only truly appreciated when one juxtaposes it with the argument against which it was employed, that is, the existence of an absurd patent. The idea of the iPad was there long before Apple made it theirs; or, rather, the fantasy was there long before any electronic company ever went to court to make it legally theirs. The real questions underlying these current legal battles between the world’s two leading electronic companies are whether such a fantasy can or ought to be monopolized, by whom, and in what format—rectangular or otherwise.