ISIS and Khorasan A Humanist Perspective

Photo by zabelin / 123RF

Photo by zabelin / 123RF ISIS, the new Islamic state that took over much of northern Iraq and northeastern Syria this past summer, directly threatens the existing states in the region. We’ve since learned of Khorasan, a splinter group of jihadists designed to carry the war to the enemy heartlands in Europe and the United States. What is going on here? The center of the Arab world has disintegrated into a multi-faceted civil war. Do we have a stake in this fight, and, if so, how do we define it and what do we do about it?

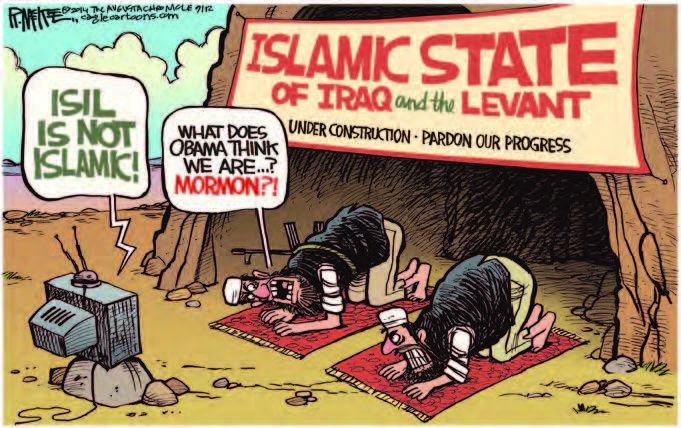

Understandably, there’s a major public debate in our country these days as to what our stake is and what strategy our government should be pursuing. It’s a debate that intensified when ISIS stuck a thumb in our national eye by publicly beheading two of our journalists, and peaked with news about the Khorasan group’s desire to attack domestically.

Humanists are just as concerned as other Americans with the major elements of the stew we find ourselves getting into, issues like oil and geopolitics, the flouting of international law and order, the gross violations of human rights, and now the threat of possible terrorist acts within our borders. But there’s another issue here that shouldn’t be left out as we try to parse out where we stand. That is the role of religion in politics generally, and especially the question of the separation of church and state.

Sharia law doesn’t just try to redefine where the line should be drawn between religion and temporal authority, it denies the existence of any line at all. The law of the land is just what the Koran and its commentaries say it is. And it’s the religious authorities who explain it all to the rest of us. It makes our own fundamentalists look like modern liberals by comparison.

How did this extraordinary development happen? In Syria you had a disparate gaggle of groups, mostly from the Sunni branch of Islam, trying to overthrow the regime run by President Bashar al-Assad, who belonged to a Shi’a sect. One of these groups spread to Iraq and forged an unholy alliance with dispossessed and unhappy Sunni officers of Saddam Hussein’s former armed forces. The jihadists of the first group supplied the ideology and the fervor; the second supplied the military expertise. It was a toxic combination that combined religious prejudice (Sunni versus Shi’a) with military clout and lust for revenge. ISIS stormed Iraqi prisons to free and recruit seasoned army veterans, it took and ransomed captives and robbed banks to get funds, and it captured a lot of the military hardware the United States had supplied to the new Iraqi army. Then ISIS captured Mosul and much of that part of Iraq where the Sunnis were in the majority, while on the Syrian side, they absorbed many of the more radical Sunni elements in Syria that were fighting Assad.

Rick McKee, The Augusta Chronicle

Ideologically, ISIS seeks to reestablish the days of glory of classical Islam when the Muslims ruled a vast swath of the then civilized world under the banner of Islam. They believe in Sharia law, based on the words of the Koran and related official interpretations. There is method in their madness: they aim to establish themselves as the true champions of Islam, opposing Muslim heretics (Shi’a and other sects) as well as adherents of other religions. They present themselves as the way to go for Muslims around the world who feel oppressed by the West generally and by the United States in particular.

I don’t want to suggest that humanists take sides in the Sunni-Shi’a conflict, which increasingly resembles the great civil wars of our own Reformation period. We do not have a dog in that fight. We can all agree, however, that it is atavistic and just plain wrong for people to go around killing each other because of religion. And we can say to religious fundamentalists in our own society: look here, do you see what all this intolerance leads to?

We can and should point out to all concerned that when the U.S. military seized the reins of power in Baghdad, we were pretty short-sighted in neglecting the sectarian implications of our postwar occupation and reconstruction programs and policies. We might remind our leaders that, as a general rule, support for nonsectarian groups and causes is better for everyone in the long run than betting on one sect as opposed to another. Secularism is the proper soil from which modern societies can grow and prosper. Theocracies lead nowhere.

Other things being equal, we should favor regimes that stand for freedom of religion and harmony between religious groups. We shouldn’t forget that separation of church and state is a basic premise of who we are as a nation. And that applies not just to humanists but to all Americans.