Such a Voice Is Needed: The Humanist Interview with Salman Rushdie

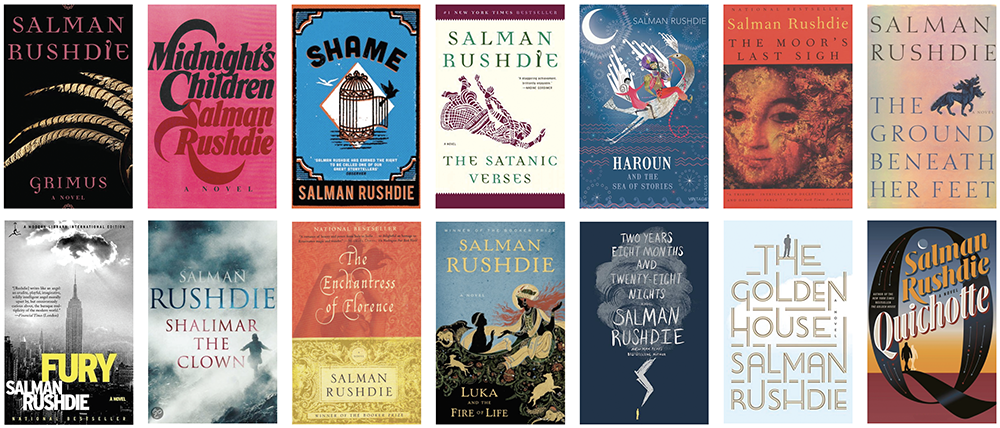

SALMAN RUSHDIE is the author of fourteen novels, has written collections of fiction and non-fiction, and in 2012 published his memoir, Joseph Anton. His second novel, Midnight’s Children, won the Booker Prize in 1981 and was named “Best of the Booker” in 1993 and again in 2008. His fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, was published in 1988 and contained a variation on a story of Muhammad adding verses to the Koran. The book ignited a huge controversy in the Islamic world, leading to Ayatollah Khomeini’s infamous fatwa calling for Rushdie’s assassination.

At the time, Rushdie explained that The Satanic Verses presents a conflict between the secular and the religious view of the world, particularly between texts claiming to be divinely inspired and texts that are imaginatively inspired. “I distrust people who claim to know the whole truth and who seek to orchestrate the world in line with that one true truth. I think that’s a very dangerous position in the world,” he said on ABC’s Nightline. “It needs to be challenged constantly in all sorts of ways, and that’s what I tried to do.”

Rushdie is the recipient of countless prestigious writing prizes and honors. He’s served as the president of the PEN American Center and helped create the PEN World Voices International Literary Festival. In 2007 he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth and in 2008 became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He’s also on the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America, a patron of Humanists UK, and a Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism. Rushdie is currently a distinguished writer in residence at New York University.

In both his fiction and his commentary, Salman Rushdie has been called courageous, controversial, erudite, irreverent, fabulistic, cosmopolitan, and more. His books have been translated into over forty languages, and move between nations, cultures, religions, nationalities, languages, and creeds, much like humanist thought itself.

In a New York Times column on February 14, 1999, the tenth anniversary of the fatwah, Rushdie posed this question:

Amid the cacophony of the professionally opinionated and the professionally offended, may a voice still be heard celebrating literature, highest of arts, its passionate, dispassionate inquiry into life on earth, its naked journey across the frontierless human terrain, its fierce-minded rebuke to dogma and power, and its trespassers’ fearless daring?

In naming Rushdie the 2019 Humanist of the Year, the American Humanist Association answers that question with a resounding “Yes.” Such a voice is needed. I was honored to present Rushdie with the award at his NYU office on April 30. His acceptance remarks and our interview are adapted here with his permission.

Jennifer Bardi: Salman Rushdie, you join a long, illustrious list of Humanists of the Year, including fellow novelists Margaret Atwood, Kurt Vonnegut, Joyce Carol Oates, Alice Walker, Isaac Asimov, and Rebecca Newberger Goldstein. Do you feel a kinship with this group of humanists?

Salman Rushdie: Well, many of them have been good friends of mine. I’ve known Margaret Atwood since we were children. And Kurt Vonnegut was very, very nice to me when I first came to America in 1981 for the publication of Midnight’s Children. He actually came along to this pathetic little book party that was given for me, and invited me out to spend the weekend with him in Long Island. He was very generous, and I’ve always remembered him with affection. As for Asimov, I used to be quite a science fiction buff, so, yes, I’ve read my share of Asimov. And yes, I do feel in very good company.

Bardi: Your fourteenth novel, Quichotte, was published in September. It’s a modern remake of Don Quixote and billed as “an epic love story set in the Age of Anything Can Happen.” Can you tell us a bit more about the book and if Cervantes’s reality-challenged character is more apt than ever?

Rushdie: Well, what I thought about Cervantes’s Don Quixote is that, on the one hand, he’s a fool. Everything he thinks is nonsense. But he also has a kind of nobility. He has his view of how things are, and he will pursue that view in the face of all evidence that it’s completely ridiculous. So that combination of comic nobility was something I liked.

I also liked how, in his great book, Cervantes is taking on the junk culture of his time—all this chivalric literature, which he thought was nonsense and was addling people’s brains, as in addling the brain of Don Quixote himself. I thought, well, we have junk culture now. We have a junk-culture president. How, I wondered, would I take on that part of our culture? That was one of the starting points.

And then there is the question of obsessive love. Don Quixote is obsessed by a woman he doesn’t know and has never met, and he keeps interfering with her life. Now, it strikes me that today, we might not see that as romantic. We might see that as stalking. So I also have a character who’s in love with a woman he’s seen on TV and decides to try and make himself worthy of her affections; he keeps writing her letters, which she keeps handing over to the police, etc.

That’s the bit that comes from my rereading of Don Quixote. But the great thing about a road novel is that it can be many kinds of book; it can change as it goes on. So part of Quichotte is a father-son journey. Part of it is a science-fiction story. Some of it is a spy novel. It goes through various metamorphoses.

Bardi: I can’t wait to read it. Thinking about Don Quixote, and more about humanism, the humanist philosophy is sometimes accused of putting too much stock in the notion of human potential and the goodness of humanity in the absence of a god. But going on the assumption that we’re all we can count on, is it really quixotic to stake out a moral position that we should step up and survive, and maybe even help each other out?

Rushdie: The truth is, human beings are flawed. We wouldn’t be human beings if we weren’t flawed. So I have no great interest in saints. And I’ve really no great interest at all in people who think of themselves as being good, because we’re all good and bad.

But what we do have is an interest in the good. Steven Pinker talks about a language instinct—I think we may actually have a moral instinct. We come into the world, and we ask our parents to tell us right from wrong. We may kick against it because children do that, but to have that framework of right and wrong is important to us as human beings. As we get older, those ideas became more sophisticated. And that’s where I think the whole humanist idea comes in: that we work out for ourselves what is right and wrong. We don’t have it handed down to us.

And as societies go through history, those ideas change. There was a time in this country, for example, when people didn’t think of slavery as wrong. And then they did. Just as our attitudes to gender relations have changed dramatically. What I’m saying is that ethics evolve as free societies develop. That’s what’s interesting to me. That’s the heart of humanism, I think.

Bardi: American humanists have long been cast by mainstream society as tilting at windmills—warning against the encroachment of religion into matters of state. So for example, sounding the alarm that the religious right poses a grave threat to civil liberties and to the freedom of the individual. Do you think as more Americans leave organized religion, they’re starting to see these concerns as more realistic and valid?

Rushdie: I think so. It’s interesting to me that the younger generation seems to be clearer about this. They seem to be less fogged by religion, and more interested in working things out in a secular, civil way. I think that’s very important.

I’ve often thought of religion as representing a kind of childhood of the human race. There was a point when we didn’t know things; we didn’t know where we came from or how we got here. And so religion arises to answer these two big questions: Where do we come from and how shall we live? Gradually, as we’ve evolved as a species and through history, we now have other explanations of where we came from. And we don’t need “how shall we live” to be handed down to us as a commandment. We can work it out for ourselves.

Bardi: Right. We just need to enlighten more people to that.

Rushdie: Well, I’m doing my best.

Bardi: You certainly are.

Rushdie: Sometimes people don’t like it!

“You should write what you know but only if what you know is really interesting. If not, go find something out and write about that.”

Bardi: You’ve been critical of younger Americans’ tendency to accept censorship in order to avoid offense. In a world of social media sound bites and a culture where an utterance or two can be lifted from a larger context and used to condemn, are people forgetting that there are indeed larger contexts? How do we get people to consume larger works of art and bigger pictures?

Rushdie: I do think it’s worrying, and the mob mentality of some social media is very worrying. I do think that a part of the younger generation’s willingness to agree that certain kinds of speech should be restricted may be for virtuous reasons. Nevertheless, to see free speech being eroded, not just by the inhabitant of the White House but also by young people for what they would consider good reasons, is worrying and disappointing in the country of the First Amendment. Because one of the great treasures of this country is the First Amendment. If you’re a professor in a university, it’s something you have to actually work against. You have to try to show young people that it’s a very slippery slope.

I’ve now spent a lot of the last twenty years in one way or another involved with the academy in this country. And actually, it’s quite encouraging to me how many students are really passionate about books. This goes against the perceived wisdom, which is that everything is dying.

And so one upside of the Internet is that there are any number of really quite interesting websites about books now, some of them started by big organizations, but many of them just started by somebody who’s passionate about books. And these sites get a lot of traffic.

Literature was never a mass-market medium. Even for Charles Dickens or whoever, the audience doesn’t compare to an episode of Friends or Game of Thrones (the television series, not the book). But the number of people who are passionate about books is consistently significant, and I don’t believe it’s really diminished. Publishers, who are notoriously gloomy and pessimistic as a breed, will tell you that book sales are up, that bookstores are increasing in number rather than closing down, and that people are actually coming back to hard copy books as opposed to electronic versions.

So, this strange form that everything was supposed to kill—radio, film, television—is anything but dead. It’s chugging right along. And I don’t care in what form people read. Whether it’s in the ears via audiobook or on a Kindle or iPad, I don’t mind. What matters is that people should consume books.

Bardi: Do you think it’s risky to write characters from marginalized groups, characters who are not from a group that you’re from?

Rushdie: It’s risky. Well, the gist of it is you face criticism for doing it badly. But I don’t believe there are no-go zones; otherwise we can only write about ourselves. I’m not a gay woman, for example, but I reserve the right to write about one. The question is whether you do it right.

In my novel The Golden House, there’s a character engaged in quite painful transgender issues. I wanted to write about these issues because they’re so consequential and controversial right now. But you can’t just sit at home and make it up. You have to get out of your comfort zone and talk to people who are having the kinds of experiences your character might have.

All the writers I admire have had the ability to write about the whole of society. Dickens could write about pickpockets and archbishops. He could write about the criminal class, the petty bourgeois, the aristocrat; the whole of society was his subject. To be able to write like that, you have to leave home. You have to get out and get your hands dirty, so to speak. Find things out. We’re all taught this great mantra: write what you know. And I say to students, you should write what you know but only if what you know is really interesting. If not, go find something out and write about that.

Bardi: Yes. Obviously, you don’t want people speaking for other people, but it’s a different thing when you’re talking about a rich, complex novel with multiple characters.

Rushdie: Yeah, I don’t believe in speaking for anyone. You know, even if I’m writing about my own ethnic group of Indian immigrants in the United States, I don’t believe in speaking for them. I’m not their spokesman. A friend of mine invented this funny term that there were writers who acted as “behalfies.” I don’t want to be a behalfie! I’m not speaking on anyone’s behalf.

I’m lucky in a way that I’ve spent my life in a lot of different worlds. I grew up in India. I lived for a long time in the UK. I’ve now lived in the US for almost twenty years. It gives me the ability, I think, to put people in all these different environments and make them characters from many different backgrounds.

I think one of the things that’s happened in the world, the shrunken world we all talk about, is that everything collides with everything else. We don’t live in neat little boxes now. Our boxes all open up into everybody else’s little boxes. That sense of how the world joins up has become a big subject for me. And because the accidents of my life have allowed me to experience the world in different places, I have a bit of a sense of how the world joins up.

Bardi: Is there anything else you’d like to say to the humanists out there?

Rushdie: I’ve always felt that it was a community that I felt part of, so I’m happy to have it made official.

Humanism’s Great Lesson

BY SALMAN RUSHDIE, 2019 HUMANIST OF THE YEAR

2019 Humanist of the Year Salman Rushdie (left) and Humanist Editor in Chief Jennifer Bardi (right)

It’s a real honor to receive this distinguished award, especially to see my name added to the extraordinary list of previous Humanists of the Year.

Thinking about my long relationship with humanist ideas, I remember being at a lecture given by the great architectural scholar Sir Nikolaus Pevsner. This was somewhere around 1967 when I was twenty years old at Cambridge University. In this lecture, Pevsner explained the difference between the High Gothic and the Renaissance schools of architecture. In the High Gothic, he said, the eye is led forward towards the altar and up towards God. By contrast, the Renaissance basilica, with its characteristic cross shape, requires one to stand at the center in order to see the whole design. In other words, the human is placed at the center, not God.

I was much struck by this idea. Humankind must be placed at the center of the building of the civilization of the world; the human scale is all-important. And when it is lost, so is something crucial about humanity.

The Renaissance architects used the unit of measurement that was based on the human scale. Monumentalism, by contrast, is the preferred form of tyrants, pharaohs, and führers. The human scale is as important in literature as it is in architecture. Lose that and the work loses its effect, its capacity to arouse and move us. Even the great epic works from the Romana to the Odyssey, from Tolstoy to García Márquez, know that the retention of the human scale is crucial. Humanity must be placed at the center and the work must be of human proportions no matter how large its sweep nor how high its ambitions.

I’ve been in my life deeply affected both by Renaissance humanism—the humanism of Petrarch and Boccaccio, of Giordano Bruno and Pico della Mirandola—and by its modern descendants with their emphasis on rationalism and a turn away from religion. And I always tell myself to remember humanism’s great lesson—the human being is the center. In the words of Alexander Pope, “The proper study of mankind is man.” Thank you again, very much, for this award.