Mastering the Camera

“He was usually not pictorially dramatic and many of his photographs appeared flat—not shocking enough for his contemporaries. The people in the photographs communicate directly to us as if they were still alive. They spill out of their historic reality to become part of our present. We see them and think we are about to know them.”

—Judith Mara Gutman, Lewis W. Hine and the American Social Conscience (1967)

The life of social photographer Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940) was full of key meetings and transitions. One of the most important was his passage between rural Wisconsin and New York in 1901. During that time young Hine attained a sense of self, learned his job, and began to develop his sensitivity for human beings. And it was then that he pioneered the world of photography and committed himself to social reform. For Hine, the move to the New York City was synonymous with teaching, immigration and, last but not least, the discovery of photography at the Ethical Culture School.

Lewis Hine’s talent seems obvious today, yet its cultivation is due in large part to the people he met throughout his life and career, foremost at the Ethical Culture School (ECS; known today as the prestigious Ethical Culture Fieldston School). The ECS was a progressive institution whose student body consisted largely of middle-class German-American Jews, first and second generation sons and daughters of immigrants. The essence of the ECS was the belief that every person was uniquely precious and irreplaceable. Known as the Workingman’s School when it was created in 1877 by Felix Adler, the ECS advocated industrial education and manual training. It was also, in Hine’s words, “designed to give special fitness to those who will be artists later on.”

As photohistorian Alan Trachtenberg underlined in America & Lewis Hine (1977): “Free from sectarian dogmas, Ethical Culture asserts that the primary religious ideal is to improve the quality of human relations: in short, deed, not creed, as Adler put it.” As a matter of fact, ECS students did not just sit in a class listening to the teacher but also took part in class activities. It was a school where children learned by doing, rather than sitting quietly in the classroom. This stage was of paramount importance since it was thanks to Frank Manny, Hine’s mentor, then appointed superintendent of the school, that Lewis Hine had the opportunity to try his hand at photography in 1904.

If Hine undertook to photograph the most underprivileged sections of the American population, the Ethical Culture School had something to do with it. Hine was first hired by the ECS to teach nature studies and geography. In 1904 Manny suggested the new idea of photographing school activities, “to interpret school life” as Lewis Hine wrote in 1937, which meant documenting science clubs, workshops, dance meetings, and art classes. While Hine knew nothing about photography and had never handled a camera before, he had studied drawing and wood sculpture, and was familiar with Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Fra Angelico, and Raphael. So why did Frank Manny choose him as photographer among other teachers in the school? The answer comes in interviews that the writer and art critic Elizabeth McCausland conducted with Hine in 1938, in which he quoted Manny as saying: “I had long wanted to use the camera for records and you were the only one who seemed to see what I was after… You were adequate, ready to learn, and used, not only me, but everyone in sight who could help.”

If Hine undertook to photograph the most underprivileged sections of the American population, the Ethical Culture School had something to do with it. Hine was first hired by the ECS to teach nature studies and geography. In 1904 Manny suggested the new idea of photographing school activities, “to interpret school life” as Lewis Hine wrote in 1937, which meant documenting science clubs, workshops, dance meetings, and art classes. While Hine knew nothing about photography and had never handled a camera before, he had studied drawing and wood sculpture, and was familiar with Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Fra Angelico, and Raphael. So why did Frank Manny choose him as photographer among other teachers in the school? The answer comes in interviews that the writer and art critic Elizabeth McCausland conducted with Hine in 1938, in which he quoted Manny as saying: “I had long wanted to use the camera for records and you were the only one who seemed to see what I was after… You were adequate, ready to learn, and used, not only me, but everyone in sight who could help.”

Hine quickly mastered the use of the camera, then formed a camera club and a class specializing in photography, which he thought would be a good way to get the kids out into the world. The club made field trips together and young Paul Strand, a soon-to-be photographer and one of Hine’s students at the ECS, became a member. Hine brought his students to meet another photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, at his gallery located at 291 Fifth Avenue. Strand became so enamored by what he experienced at the internationally known gallery that he became a frequent visitor. The main movement during those years was “pictorialist” photography, which was totally alien to what Lewis Hine was about: social documentary photography. He believed that his work should be used for social purposes and not simply hung on the walls of a museum.

Unfortunately most of the photo club images have disappeared. “During World War I, glass was a precious commodity, and some people at the school sold all his negatives as used glass,” Hine’s friend and fellow photographer Walter Rosenblum once wrote to me. “But the few photographs that have remained show that Lewis Hine was truly a superb photographer,” he concluded.

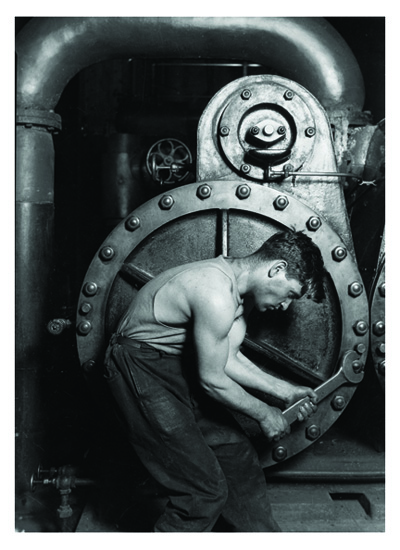

Hine’s 1905 photograph, The Printer, was one of Hine’s favorites. It captures the printer’s care while working; the way he handles the sheet of white paper and his concentration demonstrates the nobility of his gesture. But above all, the way Hine uses contrast to highlight the printer’s head and hand is a measure of his accomplishment. It foreshadows Hine’s Work Portraits of the 1920s, that is, “Hine’s focus depicting industry from a human angle,” in the words of photohistorian Daile Kaplan.

Incidentally, the subject of that photograph was printer William Oberlies. He entered the Ethical Culture School in 1904, taught printing techniques, and became a master printer. He also contributed a great deal to the school magazine, Inklings. As reported in the magazine in March 1917, “when an issue was on the press, he often worked until eight o’clock with the boys, so that it would be finished on time.”

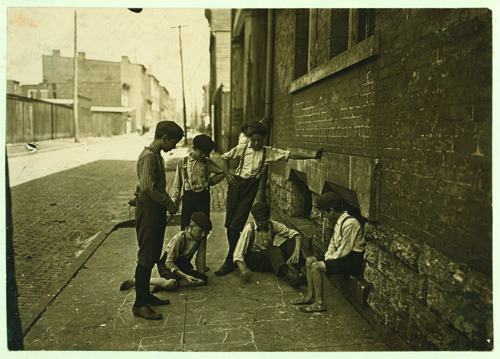

Hine’s teaching methods and first photographs for the Ethical Culture School were published in 1906 in newspapers such as the Outlook, the Elementary School Teacher, and the Photographic Times. Hine wrote the articles himself, discussing the use of photography as a teaching aid. In his essay, “Ever—the Human Document,” Alan Trachtenberg notes that Hine’s articles “are also the first serious discussion in print of the place of photography in schools—not as a ‘hobby’ but as a discipline in its own right.” In the article “The School in the Park,” it’s clear that, for Hine, books and schoolrooms were insufficient; for the wellbeing of children, the outside world had to be included within the academic year. Hine advocated school outings, such as daytime rambles through the woods or the countryside for exercise or social intercourse. Throughout the article, Hine showed that in all these outings, the camera was a valuable assistant. Of course, pupils were allowed to take their own pictures with the camera, which, Hine wrote, “serves to record conditions at the places visited so they may be better described to other classes after the trip.” Pupils were asked to write compositions and to find words for songs.

Hine’s teaching methods and first photographs for the Ethical Culture School were published in 1906 in newspapers such as the Outlook, the Elementary School Teacher, and the Photographic Times. Hine wrote the articles himself, discussing the use of photography as a teaching aid. In his essay, “Ever—the Human Document,” Alan Trachtenberg notes that Hine’s articles “are also the first serious discussion in print of the place of photography in schools—not as a ‘hobby’ but as a discipline in its own right.” In the article “The School in the Park,” it’s clear that, for Hine, books and schoolrooms were insufficient; for the wellbeing of children, the outside world had to be included within the academic year. Hine advocated school outings, such as daytime rambles through the woods or the countryside for exercise or social intercourse. Throughout the article, Hine showed that in all these outings, the camera was a valuable assistant. Of course, pupils were allowed to take their own pictures with the camera, which, Hine wrote, “serves to record conditions at the places visited so they may be better described to other classes after the trip.” Pupils were asked to write compositions and to find words for songs.

While nature was of utmost importance to Hine, he did not neglect the industrial world; harbors, flour mills, silk factories, sugar refineries, potteries, and other industries became subjects. Note that in 1901 Hine had entered the University of Chicago for a year. One of his teachers was John Dewey who invited teachers to include psychology in the curriculum by “creating an environment where the child found herself or himself confronting problems that aroused interest in science, art, and history.” What’s important here is that Hine learned how to handle children, and he understood the conditions needed for them to improve their awareness of the world.

Taking the ECS pupils in hand, it’s also worth noting just how much Lewis Hine liked children, how much he wanted them to be fulfilled in this world. His professionalism showed here, because he was perfectly aware of his own limits as a teacher and educator. As he cleverly put it in his article, “An Indian Summer”: “the schools can do much, but the main responsibility clearly rests upon the parents.” At that time he surely didn’t realize that parents’ responsibility would change a few years later, when thousands of children would be sent to work all day long.

With Frank Manny’s support, it would have been a shame for Hine to stop while he was doing so well photographing school activities. But why not also take pictures of the massive arrival of aliens at Ellis Island? As a matter of fact, it was Manny who suggested the idea so that, according to Hine’s Notes on Early Influence, “the children of later days feel the same regard for Castle Garden and Ellis Island that they had then for Plymouth Rock.” This was the very starting point of Hine’s renowned photographic career.