Gore Vidal: 1925-2012

“Style is knowing who you are, what you want to say, and not giving a damn,” Gore Vidal famously said. I came across the quote in his Los Angeles Times obituary. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard it; Gore said it to me himself. Really, it’s a humanist quote, applicable to any form of spirituality or philosophy that seeks happiness and enlightenment. The not giving a damn part was perhaps a bit aggressive, but that was Gore, and it’s me too.

I entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1999 thinking that I would one day become an admiral. After realizing the imperial nature of our government and armed forces, I left the Navy in 2005. The transition to civilian life was the most difficult task I have ever had to accomplish—ongoing, really. From 2005 to 2008 I lived in New York City and gave much of my time to Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) and a group called Military Resistance. These two groups were my identity for those three years. They’re still a part of me, but I’ve since found balance and peace with the entire world and myself—we’re actually inseparable.

I entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1999 thinking that I would one day become an admiral. After realizing the imperial nature of our government and armed forces, I left the Navy in 2005. The transition to civilian life was the most difficult task I have ever had to accomplish—ongoing, really. From 2005 to 2008 I lived in New York City and gave much of my time to Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) and a group called Military Resistance. These two groups were my identity for those three years. They’re still a part of me, but I’ve since found balance and peace with the entire world and myself—we’re actually inseparable.

Finding that balance began when I moved to Los Angeles, California, in September 2008. Two months later, Gore Vidal called me on my cell phone, catching me in the middle of a slight hangover, and invited me to his house the following day. Gore’s friend Jean Stein, whom I’d met in New York through anti-war activism, had told Gore I was a Naval Academy graduate engaged with anti-war organizing and that he should meet me.

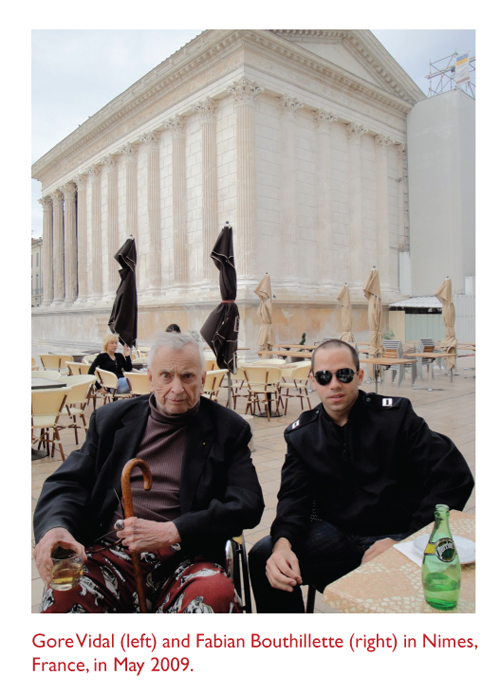

The next day, Gore received me in his bedroom (where he died on July 31, 2012) and thus began a twenty-two month partnership that finally got my head settled into the civilian world, and forced me to mature into a man at a rate that was at times overwhelming. Basically, Gore challenged me to know who I am, know what I want to say, and not give a damn. He drilled me by pushing my brain and body to the brink of exhaustion as I accompanied him and pushed his wheelchair all over Los Angeles, New York, and much of Europe. He never referred to me as his assistant, rather as his “naval attaché.” Serving him was the greatest duty of my life.

Gore was many things to many people, but at his core he was an anti-war veteran and also a humanist. He avoided front-line duty in World War II (thanks to his family connections to West Point) but lost many childhood friends. His best friend (and lover), a Marine named Jimmie Trimble, was killed on Iwo Jima. Gore never forgave the military machine for Trimble’s death, nor for the deaths of all those used as cannon fodder. Iwo Jima was a battle of vanity, unnecessary for the conquest of Japan. Trimble and so many others were slaughtered for the glory of the United States and its generals.

Fortunately, the United States is going through an evolution of consciousness right now that’s leading to some sort of revolution. Gore Vidal was on the leading edge of that evolution—the “tip of the spear,” as we military types so often like to think of ourselves. It was he who longest taught, and resisted, the perils of the top 1 percent accumulating most of the nation’s wealth. And for my taste, Gore did it the best. His writings, specifically the seven historical novels that are commonly referred to as his “Narratives of Empire,” give personality and emotion to our nation’s history. Understanding Gore’s historical context would make any future political movement more united and therefore more successful.

While the loss of Gore and of his powerful voice is a blow, I feel sure that his lessons can be advanced into a new era, a humanist era, where love and compassion are the driving emotions.