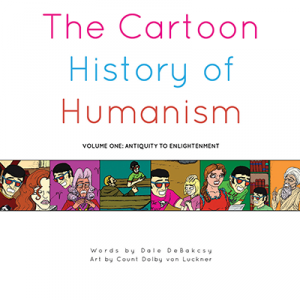

The Cartoon History of Humanism, Volume One: Antiquity to Enlightenment

BOOK BY DALE DEBAKCSY

HUMANIST PRESS, 2016

122 PP.; $24.99

The conceit from which The Cartoon History of Humanism, Volume One: Antiquity to Enlightenment launches is as funny as it is paradoxical. In fact, its humor comes from its contradictory nature. As a child, our protagonist Dave makes fun of a passing logical positivist, who then proceeds to do something very antithetical to logical positivism. He curses Dave, forcing him “to wander time and space conversing with humanist philosophers until he learns his lesson.” One imagines the lesson might be that there is no such thing as a curse!

The ambition of Dale Debakcsy and his cartoonist alter-ego Count Dolby von Luckner is not heresy, of which many of his profiled subjects are accused. Nor has he set out to create a complete and unsterilized history of humanism, conventional wisdom and prejudice be damned. DeBakcsy just seems to enjoy uncovering and exploring the lives of, as he puts it, “my favorite thinkers and doers of the humanist tradition”—people he ranks as truly badass. In the course of unraveling their awesomeness for his own edification and pleasure, he does the same for us. He proceeds to illustrate the lives of not only familiar dramatis personae of humanist history but others heretofore largely ignored and purposely omitted.

If you’re already a fan of Debakcsy, whose cartoons are regularly featured on TheHumanist.com, you will no doubt be familiar with his droll yet authoritative shakedown brand of historical retelling. The thirty-two (plus three never-before published) profiles that make up the volume are concise and entertaining. They’re also filled with statements of import and interest, punctuated with whimsical pith, amusing contemporary references, and lively turns of phrase, such as, “Among humanity’s Not Ever Thought sentences, this must rank as one of the NotEverThoughtest.”

DeBakcsy depicts philosophers, artists, statesmen, mathematicians, logicians, orators, and some with so many titles that it would suffice to call them polymaths. There are also priests, abbesses, bishops, and other members of the creed-man heathen hater’s club. They are the usual suspects: Rushd, Hume, da Vinci, and Voltaire, among others. But the book also includes those not directly linked to humanist history who are no less important, like Arnold of Brescia, John Toland, and Isabella d’Este. There is even one Marvel-ous bonus god, Loki, who may be the most human.

We read of Peter Abelard’s revelatory idea that love overcomes dogma as well as the appeal of Voltaire’s Candide to helping community. The author regales us with the genius of Lucretius and Leonardo while also pointing out their failures, letting us know in a hilarious manner that even the smartest are imperfect. We feel suspense as Arnold of Brescia almost succeeds with his anti-papal commune. We entertain hope as we read about truly compassionate leaders Isabella d’Este and Henry IV, and then are deflated as a vindictive, power-hungry religion takes hold once again. We are inspired by strong women like Heloise d’Argenteuil claiming boldly that reproductive fate doesn’t dictate personal freedom (in the twelfth century yet!) and Grazida Lizier, a peasant who took down mighty Catholicism ideologically. Pierre Bayle claims morality from shared humanity—the idea that an atheist society is just as moral, which we are still shouting to the rafters. Deism and determinism appear again and again, from the likes of Anthony Collins and Hermann Reimarus. I was truly invigorated by the depiction of the latter’s revelation that the Apostles basically made it all up and also by David Hume’s brilliant massacre of intelligent design theory.

Humanist themes are addressed throughout The Cartoon History in short but informative chapters that tempt us to investigate further as soon as our laughter dies down.

The cartoons are truly a fun diversion. The strips themselves, made up of four simple panels, feature robed characters and pen strokes somewhat reminiscent of Robert Crumb. The humor of these two-dimensional drawings relies much on the pure absurdity of the basic facts observed from the future—but also in the clever visual riddles Debakcsy leaves for us.

Both the background and mise en scène in the panels are fairly stark, save the images on Dave’s t-shirts. While they’re something of a challenge to decipher, I found myself making a quite enjoyable game of doing so. For instance, in Chapter 4, Dave’s shirt features a play on “Be Afraid” with a picture of Sigmund Freud in lieu of the last syllable. I decoded eleven of them but I won’t spoil the fun and give any more away. Just a hint—most feature famous writers, philosophers, and thinkers. (If you get stuck, email me and we can compare notes.)

Debakcsy doesn’t concern himself much with the strict regimen of the obsessive historian, eschewing footnotes and endnotes. He does provide suggestions for further reading at the end of each chapter, and, given their fastidiousness combined with his erudition (it seems he’s actually read them all and some even in their languages of provenance), the reader can rest assured he got at least most of it right. Also, I know Debakcsy isn’t one to bow to convention, but some sort of summation tying things together with his personal thoughts would have been interesting in my opinion.

As I absorbed the entirety of The Cartoon History of Humanism, I found myself pining for the great outlaw historian of the proletariat, Howard Zinn. Can you imagine a new and revised collaborative A People’s History peppered with panels of snark-filled dialogue balloons emanating from sometimes obscured but always important and fascinating historical figures?

While we await Debakcsy’s next volume, let us content ourselves with this fun-storical edutainment and count ourselves “von Lucky” for his ability to bring forth some of the heroes of humanism, both well-known and unsung.