A Centennial to Reckon With: Honoring Black Suffragists

African-American women standing with civil rights activist Nannie Helen Burroughs, holding a banner reading, "Banner State Woman's National Baptist Convention"

African-American women standing with civil rights activist Nannie Helen Burroughs, holding a banner reading, "Banner State Woman's National Baptist Convention" The first ballots cast by women were lauded as a giant step for womankind. Following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, women were allowed to do the unfathomable. Not only could they voice their opinions, they could now codify these opinions in the form of a vote for one candidate or another and in favor or against any ballot measure. For decades, suffrage for women had been vehemently opposed by the creators and gatekeepers of our government—white upper-class men—on the basis that women were intellectually inferior. After the seventy-year battle for suffrage, led by iconic figures such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, women’s full participation in democracy was much celebrated.

This version of the campaign for women’s suffrage leaves out some very hard truths. While some women (read: white women) were bounding ahead towards equality, others were deliberately left in the dust, namely Black, Native, and Asian women.

In an era long before Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality,” the mainstream women’s suffrage movement struggled to address the specific plights and rights of newly emancipated Black women, and prominent suffragists who had advocated for Black liberation came to see the cause as unworthy if it meant that white women weren’t also immediately reaping the benefits. Newly emancipated Black Americans were engaged in a struggle for their lives against the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, lynch mobs, and Jim Crow laws—all of which was ignored by white women suffragists.

Ida B. Wells

Elizabeth Cady Stanton has long been lauded by nontheists for exposing the role religion played in keeping women subordinate to men. While her contributions to both feminism and secularism merit high praise, the legacy she leaves behind is complicated by her callous denigration of Black Americans in the campaign for suffrage. Rather than supporting Black people’s right to vote so that they could gain greater political efficacy, she was offended by the prospect that Black men would attain suffrage before white women. “As the celestial gate to civil rights is slowly moving on its hinges,” she wrote in 1865, “it becomes a serious question whether we had better stand aside and see ‘Sambo’ walk into the kingdom first.” Opposed to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, Stanton argued that white women should receive the right to vote before Black men because “we have a power that is to develop the Saxon race into a higher and nobler life and thus, by the law of attraction, to lift all races to a more even platform.” In other words, suffrage for white women was more important and more beneficial for all parties than granting the vote to Black men, much less Black women.

Mary Church Terrell

Similarly, Susan B. Anthony abandoned the fight for Black suffrage for political convenience. Anthony originally advocated for Black suffrage until the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment provided voting rights to all men but no women, fracturing alliances between Black suffragists and the mainstream suffrage movement. Anthony felt betrayed by Black male suffragists, and this, combined with pressure from white Southern women, changed her activism. She began to advocate against the presence of Black women in the women’s suffrage movement, noting that including Black women would likely lose the support of white Southern women. Thus, Black women’s suffrage had to wait for another political moment.

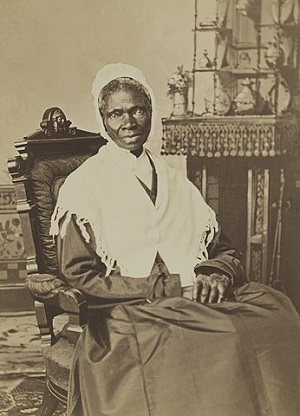

Sojourner Truth

Nevertheless, while white women worked to erase Black women from the movement, Black women continued to advocate for women’s suffrage for all women. Ida B. Wells, an acclaimed journalist, founded the National Association of Colored Women’s Club to address civil rights and women’s suffrage. At the first suffrage parade in Washington, DC, in 1913, Wells was told to march in the back with other Black activists, but she boldly refused. She pretended like she was walking away, only to return to march alongside white women. As the founder and president of the National Colored Women’s Association, Mary Church Terrell tirelessly advocated for Black suffrage, particularly for women. She picketed at the White House and campaigned for the mainstream movement to recognize the importance of Black women’s suffrage.

Many Black women activists recognized the double burden that Black women faced and continued to advocate for the power women’s suffrage would give them. Among the loudest voices were Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who made a speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1866 emphasizing the various oppressions at play in Black women’s lives and the importance of suffrage for addressing them. Sojourner Truth, at the 1851 convention, gave a bold address titled, “Ain’t I a Woman?” It was an impassioned speech that laid bare all that Black enslaved women had struggled through only to be denied a role in a movement pretending to fight for women’s equality.

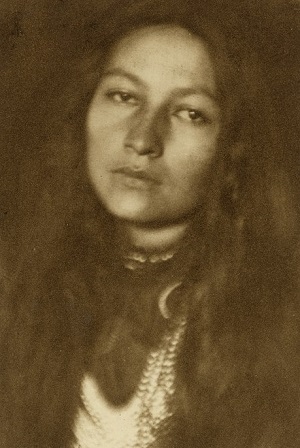

Zitkala-Sa

Histories of the women’s suffrage movement also fail to mention the contributions of Indigenous and Asian American women. At a time when the US government’s policy regarding Native people consisted of land grabbing and forced assimilation, Native women like Zitkala-Sa of the Yankton Sioux worked to obtain citizenship and voting rights for Native people. White feminists were inspired by the matriarchal structures of many Indigenous tribes, particularly women in the Iroquois Confederation, and invited them to speaking engagements and parades. In 1913, at the same parade where Ida B. Wells was told to walk somewhere else, white women wanted to include a float for Native women that was decorated to represent Native women as they were in the past—with buckskin and braided hair. Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa saw through the stunt and decided that, instead of organizing the float, she would march with her classmates and teachers from the Washington College of Law.

Although Asian Americans didn’t technically exist at the time due to laws against Asian immigrants’ naturalization, Asian women suffragists still existed. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a Chinese immigrant, was a prominent figure in the New York women’s suffrage movement by age sixteen. She led a parade for suffrage in New York City on horseback in 1912 and advocated for women’s suffrage even though she knew she wouldn’t personally benefit from the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin

As women celebrated casting their ballots in the presidential election of 1920, obstacles were erected that would stand for the next forty-five years to suppress the vote for Black women. Native and Asian women were told that passage of the Nineteenth Amendment was still an important moment for them, not because they could vote, but because they soon would reach the status to which white women had ascended. “Soon” became decades. Although Native people were granted citizenship in 1924, Jim Crow-like voting restrictions prevented them from voting until an Arizona Supreme Court decision in 1948. Asian Americans slowly gained suffrage one ethnic group at a time until 1952, when the McCarran Walter Act granted rights to all Asian Americans. And, at last, in 1965 the passage of the Voting Rights Act prohibited voter discrimination on the basis of race.

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

It would be nice if the history book on suffrage could close there, in 1965, with a stroke of Lyndon B. Johnson’s ballpoint pen. However, the suppression or denial of voting rights still affect Americans today. Where there used to be literacy tests barring Black Americans from polls, there are now restrictive voter ID laws. Felons, in many states, lose their voting rights for years, sometimes permanently. For centuries, gerrymandering has been used to draw congressional districts in a way that disenfranchises the votes of people of color. Finally, the US response to the coronavirus pandemic is bound to catalyze disenfranchisement in November’s election. It’s strange that in a country where your vote is supposed to represent your voice, the government not only refuses to listen to some, but actively bars them from speaking at all.

As we mark the centennial of women’s suffrage in America, it is necessary to honor the work of white suffragists by acknowledging both their triumphs and their flaws. We must also elevate the bravery and dignity of Black, Native, and Asian women who campaigned for the same cause. And when the election comes this November, those who can should vote while thinking of all who had to fight to participate in one of the basic rituals of our democracy.