The Ethical Dilemma: Faking Religion and the Black Sheep

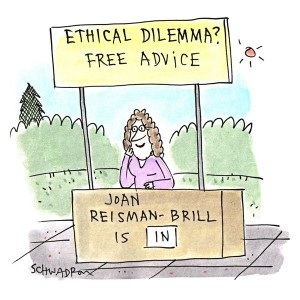

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Method(ist) Acting: I am thirteen. I am still trying to figure out myself, and I have known I was an atheist since I was a lot younger—but my religious family doesn’t. I hate having to hide my secret from the people I love. My family is Methodist. They are pretty accepting of others (including the LGBTQ community), but they are very faithful. I don’t know how they would feel about me being an atheist.

Currently I am “faking” my religion. I go to my grandfather’s church, where he preaches, and it is difficult because he tries so hard to really “preach” when I am there. I don’t believe what he says on that subject.

If you could give me some advice on what I should do, it would be greatly appreciated.

—How Can I Test The Waters Without Rocking The Boat?

Dear Test,

A lot of people start recognizing their atheism around your age, just as they are turning into adults. This is great, because they can spare themselves getting stuck on the wrong track and then realizing their mistake when they’re older—and perhaps married and with children in a restrictively religious situation. But it’s also challenging because, at thirteen, you still have more years of being dependent on your parents, which includes living in their home, on their dime, and by their rules.

It sounds as though your parents are pretty cool. The fact that they accept LGBTQ suggests that they’re progressive, and that might extend to other areas. But people who are progressive in theory may be less so when it comes to their own children.

When I was a kid, I discovered I could get a reading on my parents’ positions by raising “how do you feel about” dinner table conversations on topics such as interfaith marriage, interracial marriage, or homosexuality (back then that discussion didn’t go anywhere near same-sex marriage—just whether gays and lesbians were acceptable in society at all). I couldn’t help but notice that my father would respond as though I personally was planning to become gay or marry outside my faith or race. We had some pretty energetic debates, and I realized some things would not go down well with my dad if it really were his daughter we were talking about.

You could try the same thing: raising topics because perhaps you’re thinking of writing an essay for school, or because you’re curious about things in the news, or whatever pretext you choose. Bringing up the mounting research that shows the rise of the “nones” and the decline of religions is a great way to broach the topic of atheism and see how your parents react. You could even venture a “How would you feel if I became an atheist? Just asking,” to get a sense of how they’d react. Although that might make your family suspicious, many people find that even if they say loud and clear that they are atheists, their loved ones behave as though they didn’t hear. Even your parents might not be able to predict how they’d react if the hypothetical were to become actual.

It’s up to you to gauge your parents’ anticipated response and determine whether or not you want to tell them anything. If you do decide to fill them in, you have to decide whether to ease into it with dropped hints or to take the leap with a straightforward announcement. There’s no good reason to make life miserable for yourself or them if they’d react badly to your faithlessness. But if you think they might be able to absorb the news without too much drama, you might want to start with clues (e.g., “I’m really not comfortable attending Grandpa’s church—and I have a lot of homework for tomorrow, which would be a much better way to spend that time”) until you feel ready to come out with the whole truth.

There’s no shame in waiting a few years until you can be out of your parents’ house for college or career and not dependent on their financial or emotional support (although emotional support from parents is something to cultivate for as long as possible). Once you are independent, you can tell your family as little or as much as you care to.

In the meantime, keep in touch with fellow atheists and humanists through sites like this one, any local organizations you can connect with, or just friends (your age and adults) who share your perspective. If you must keep going to church, use that time to daydream, or ponder what you want to do with your life, or check out what everyone’s wearing, or whatever. Those are probably the same things just about everyone else there is actually doing.

Soul Singer: I have what some may consider a minor ethical dilemma, but it does impact me. First, a bit of background: I was born into a Christian family. My dad was a minister, my sister became a minister, and my brother switched denominations, but is still very religious. I’m the black sheep! At first I thought I wanted to become a minister, but the older I got and the more I thought about things, I realized that I didn’t really believe that stuff or buy into it. I realized later in life that many of the things in the Bible that some consider “gospel truth” are in reality allegorical or metaphorical examples to lend support to religious belief. That doesn’t make them any truer.

My wife and I share the same beliefs, happily. We began taking our two daughters to a Unitarian church at one point but left the area and did not pursue another in our new location. We raised our daughters to be independent thinkers and ethical, moral individuals. We did not pursue an atheist identity with them. As it happens, and interestingly, one daughter shares our belief system, and the other has become a very conservative fundamentalist churchgoer.

Now at age seventy-six, retired from a career in education and social work, I still can get emotional hearing some of the songs I sang as a kid in choir and in church. However, it is the music, rather than the message, which gets to me.

As an adult, I joined the Barbershop Harmony Society and am still a member today. I love singing barbershop harmony! When those chords ring, the goosebumps run up and down my arms and legs and just make such wonderful feelings. However, as with many such organizations in the US, the religious arm has a very strong hold on it. We sing lots of religiously-oriented songs. Many choruses, including my own, provide small choruses or quartets to sing Sunday services for local churches. In Arizona, many choirs take the summer off, and our chorus fills in with three or four church songs. I have done those performances, supporting my chorus, in the past but no longer do them.

I guess the dilemma is how to continue enjoying the barbershop harmonies without also singing the religious songs or participating in the religious activities. I suppose I could just not sing when we sing spirituals or other religious songs, but it can be awkward to be standing on the risers with my friends not singing while they are singing. Do I take a public humanist/atheist stand, or just continue floating along, picking and choosing the songs I sing?

I think I have answered my own question, but would be interested in any thoughts you have to share.

—Just Move My Lips?

Dear Lips,

I can’t tell if your answer to your question is the same as mine. I too have sung in choruses all my life, starting with elementary school assemblies that included Christmas carols, college choirs that did church services on Sundays, a tiny choir that did synagogue services on Saturdays, an a cappella jazz group that performed for senior citizens and anyone else who offered us gigs, and an outstanding 200-voice group that performs all sorts of works, including both the Messiah and Not the Messiah in Carnegie Hall. And every group was comprised of members of various faiths and no faith. The unifying principal was our shared love of performing choral music.

I don’t think you need to skip the objectionable songs. In fact, I think you’d do your group a disservice to take up space on the risers without providing the desired sound. The whole point of choral music is for each person to carry his respective voice part in concert with his colleagues, so that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. You are right to excuse yourself from the church events if they make you uncomfortable and they are not a requirement for membership in the group. But when it comes to a spiritual or two interspersed with secular tunes, I say just throw yourself into the hallelujahs and amens, and luxuriate in the sound and rhythm. Spirituals and religious pieces are the roots of countless great musicians because the music is so powerful (and because, until recently, most music was commissioned and supported by religious organizations). And a great deal of it, particularly spirituals, is more about enduring than adoring.

Don’t kill your joy by overthinking this. Finding a singing group you enjoy and that values your participation is a wonderful thing. Take your own advice: Enjoy the music, and don’t sweat the message. Most of your listeners will do the same.