The Ethical Dilemma: Same-Sex Wedding Cake Business

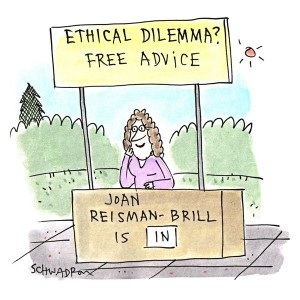

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Should Same-Sex Couples Have Their Cake? Many states have been passing laws that make same sex marriage legal. Not all businesses in the wedding industry are embracing the idea of assisting gay and lesbian couples in arranging their wedding ceremonies. Do you think it is ethical not to help these people?

—Rights or Wrongs?

Dear Rights,

Succinct question, meandering answer. This is the kind of issue I struggle with and find eludes any pat or blanket response. The positions reflected in laws may not always, or ever, be just or ideal in all circumstances and from all perspectives. They may, by necessity, put down one group in the interest of bringing equality to another. In some cases, specific laws that might make things more clear-cut do not (yet) exist, and in other cases laws that exist don’t deserve to be enforced (such as those that bar atheists from holding public office). Laws must be revised periodically to keep up with evolving social attitudes and circumstances; there is an art to applying and interpreting laws; and laws are only a crude stab at fairness.

My inclination is that if someone doesn’t want my business, I don’t want to give it to them—let alone force it on them. But that assumes I have decent alternatives. Looking at civil rights history, it’s clear that laws were necessary to make restaurants, hotels, shops, jobs, education, restrooms, etc. available to everyone, regardless of color. The alternatives were separate or non-existent and certainly not equal. I can sympathize with clergy who cannot in good conscience, according to their dogma, join together two people of the same sex, even if I don’t sympathize with their doctrine; and I’d advise rejected couples to find someone else (perhaps a Humanist Celebrant) who is happy to do the job. But that might mean they can’t get married where they want (such as their childhood house of worship), in which case a battle might be worth the trouble—not only for them, but also for future couples. Interestingly, as acceptance of same-sex unions grows, LGBT couples may find more resistance from clergy if they also happen to be interfaith.

When one Rhode Island florist after another refused to deliver flowers from the Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF) to high school activist Jessica Ahlquist, who had successfully campaigned to remove a prayer from her public high school’s wall, an out-of-state florist stepped up and got loads of rewarding publicity—while the refuseniks were slapped with a lawsuit. But what if individual Rhode Island postal carriers refused to deliver mail to Jessica or from FFRF, or if her local pizzerias refused to deliver her pies? Postal workers are required to do their jobs, but what about a ma-and-pa pizza shop? Lines must be drawn, but the question is where?

Currently there’s a case about a baker facing a religious discrimination suit for refusing to write “God hates gays” on a cake. This one may actually end up being treated as a hate speech issue rather than a free expression or religious freedom issue, turning the table on that lovely Bible-thumping customer. But should a baker who willingly complied with such a request be viewed as simply filling an order, or be subject to prosecution (or at least scorn) as an accessory to hate speech? What about people who reprint Charlie Hebdo cartoons or forward hacked nude celebrity photos?

These may seem to be tangents, but they all have points of contact with the original question. In a free society, should anyone be compelled to work for someone whose values they despise, or perform an act that violates their own beliefs? There are so many instances where affirming one party’s rights entails denying another’s. Nuance seems to be a meme these days, and there are all kinds of nuances in these kinds of questions. How to respond often varies case by case and depends in part on how much the participants are willing to spar vs. how much they prefer a path of least resistance; to what extent they have other reasonable alternatives; and to what degree their action or inaction sets a precedent for future cases. In his January 8 “Cake Wars” piece, TheHumanist.com columnist Luis Granados made the distinction that a business can refuse to promote a political message they disagree with (i.e., putting “God Hates Gays” on a cake) but can’t discriminate against customers seeking their usual services based on their race, religion, sexual orientation, and so on.

While forcing people to serve others against their will is usually not the ideal way to get them to tolerate different views, and often results in backlash, coercion (legal, or public opinion, or tactics such as boycotts) can lead to resignation, which may lead to a new normal. Maybe compelling reluctant vendors to work with same-sex couples today will pave the way to business-as-usual service in the future.

I commend those trailblazers who demand their rights in a heel-dragging but evolving world. But I also respect those who prefer not to make waves, and to give objectors—however wrong-headed they may be—more time to come around, even if some individuals never will. I acknowledge the distress of the Archie Bunkers who cling to the old order, which genuinely looks like morality and righteousness to them, even if I rue their views.

Hopefully, we are moving in the direction of enabling LGBT people to fulfill their right to have their cake—eventually without making anyone else eat crow or swallow a bitter pill. And in the meantime, many in the wedding industry are thrilled to be supplying the unprecedented demand from same-sex couples, without lower bids from less progressive competitors. I’m sure these suppliers would defend the right of others to refuse profitable jobs they themselves are more than happy to take.