The Ethical Dilemma: Should I Share My Atheism With My Church-Going Family?

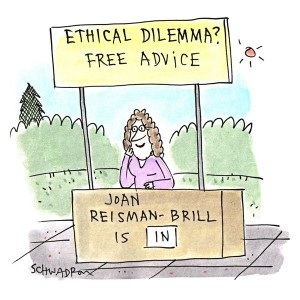

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Should I Share My Atheism With My Family? I have recently completely separated myself from any religious beliefs, after living in a Christian family for over twenty years. This happened after a lot of study and reading, and bringing myself to the (maybe not very) obvious conclusion that every religion is just an attempt by humankind at giving meaning to its own existence.

My dilemma right now is, should I try and pass this information on to my sister and parents (who were brought up the same way I was) or should I let them live their life the only way they know how? I have not told them that I became an atheist.

All my parents do besides their job is go to church and hang around in church meetings. However, my main worry is my sister, who is 18 with her entire life ahead of her. There is certainly still a chance for her to live a more fulfilling life than that of going to church every Sunday. Completely removing religion from my mind was a very saddening and painful process (meaning of life issues, etc.—things I never had to think about), and I am sure that it will be even harder for her. Our reality pretty much gets pulled away and it is harder than it might seem to get past it.

My biggest worry is that if I attempt to pass this information onto my sister, she will reject it, and be extremely sad that I gave up religion and am going to hell or whatever (and she is extremely emotional). Any thoughts on what to do?

—Speak Now Or Forever Hold My Peace?

Dear Speak,

In my experience, if you tell people what you believe, and advocate believing it, and even offer plenty of great reasons to do so—nothing will happen. I’ve mentioned my atheism to certain people repeatedly over the years, and each time they act as though they never heard me mention it in the past, or even in the present. A hallmark of faith is hanging on to it no matter what. The stronger the arguments against it, the stronger the conviction. Your parents in particular are unlikely to abandon their religion just because you endorse it. And does your sister heed everything you say?

A preferable approach is essentially to mind your own business but, transparently, allowing your family to glimpse what your business is: Simply speak for yourself, about yourself, and only when it’s relevant to what’s going on. For example, if someone invites you to accompany them to church, you can say “no thanks.” And then if they ask why not, you can explain that you’re not a believer. No need to volunteer more than anyone seems interested in hearing, or hounding everyone with arguments and lectures on why you’re right and they’re wrong. If someone really indicates they want to listen to what you have to say, then go ahead and expound, but back off if they begin to look uncomfortable or about to nod off.

And what makes you so sure your relatives’ lives are unfulfilled? Bear in mind that your parents’ and sister’s church-going may have more to do with community and habit than with any conscious or unconscious religious beliefs. It’s just what they do, and maybe it makes them feel fulfilled—by providing companionship, direction, meaning (even if misguided), routines, answers to unanswerable questions (even if false), plus celebrations and nice meals (often the biggest draw for many religious organizations).

You don’t want your family imposing their beliefs on you, so why would you feel compelled to impose yours on them? Just be yourself, model how your life without religion is rich and moral and suits you, and leave the door open for them come to their own conclusions, at their own pace, about whether your perspective might have any appeal to them.

Donating Kid’s Stash: Every Halloween my kids collect ridiculous amounts of candy. They sort it out, put their favorites in bags with their names on them, and give me the rest to donate as I choose. This year my daughter netted more than ever, left it spread out in piles all over the living room floor and went to bed completely exhausted. The next morning when an acquaintance stopped by, I made a little bag for him while I let my daughter sleep into the afternoon. When she woke up, she instantly noticed some of her loot was missing, and went ballistic on me. I went ballistic right back about the fuss she was making over a little candy when she had tons left. Later she announced she had taken what she wanted and the rest—half a dozen shopping bags full—was all mine.

When I calmed down, I started thinking about the way she knew some of the candy was missing: There had been a few unique items she wanted for herself, which I had given away. I really feel bad about that. Do I owe her an apology for giving away her stuff and yelling back at her? Does she owe me one for yelling at me?

—Candy Crush

Dear Candy,

Ever see Jimmy Kimmel’s prank where he has parents send in videos in which they tell their kids (falsely) that they ate all their Halloween candy, and then watch the reactions—which include tears, despair, rage, and dismay (“Mommy, how could you?”). As funny and harmless as it may seem, it’s an awful thing to do to a child, especially one who trusts you to protect her interests.

In this case, even though there was more than enough candy to share and it all looked the same to you, you made a bad call. You shouldn’t have jumped the gun and given away a single morsel until you child had taken her favorites and given you the go-ahead to dispose of the rest, as has been your tradition. Consider the cost of sending your visitor away empty-handed, versus the cost of violating your child’s sense of security. She believed she could leave her candy unattended while she collapsed, after having rung every doorbell in town and lugged all that loot home. Next year she’ll be afraid to conk out until she grabs her booty and hides it under her pillow.

So apologize for digging into her goodies prematurely, acknowledge the validity of her disappointment at losing her favorites (maybe you can replace them?), and promise that you won’t do it again. If you don’t like having Kisses and Reese’s Pieces all over the living room the next day, agree in advance where else she can do her sorting, or whether she must bag what she wants on October 31 before she goes to bed. Your admirable impulse to share the bounty must take a backseat to her skimming off her pick of the litter first.

And then it would be nice if she not only accepted your apology, but also acknowledged that both of you over-reacted. You should lead, and if she doesn’t follow your lead, remember that you are the only adult here. You have all year to work on issues of control and trust and generosity, and what things are more and less appropriate to get mad as hell about.