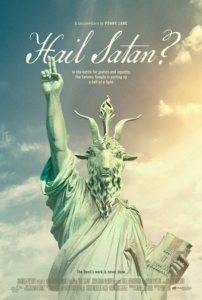

“Humanism with Horns”: Hail Satan? Film Review

(Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.)

(Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.) The grand cosmic reversal featured in the documentary film Hail Satan?, directed by Penny Lane (Our Nixon, Nuts!), is at least as old as John Milton, whose Satan has appeared to readers and critics for centuries as a sympathetic figure in contrast to the one-dimensional, totalitarian God. The stakes are high when good squares off against evil, but even higher—as in Milton’s Paradise Lost or the works of Nietzsche—when we wonder whether our whole moral edifice isn’t upside down in the first place, whether the accepted version of evil isn’t actually good. Though it’s not explicit, the thrill of philosophical disruption on this scale is one of the things that makes Lane’s film go.

On its surface, Hail Satan? is a straightforward (if unashamedly sympathetic) report on the Salem, Massachusetts-headquartered Satanic Temple, which has coopted that “other” set of Christian symbols, leveraged the freak-outs they still seem capable of producing in Christians, and created an international movement while reinvigorating debate over the Establishment Clause of the US Constitution.

The central principle of the Satanic Temple (and of Lane’s film) is, I think, unassailable: in a secular democracy the government must remain neutral with respect to specific religions, and this principle cannot have meaning unless it is applied with equal force to religions that might, at least in their standard iterations, revolt or terrify regular folks. Is the Satanism of the Satanic Temple really a religion? As pointed out by the only reviewer I’ve come across who panned the film, Lane doesn’t meaningfully take up the question. Perhaps it’s taken as given. After all, in addition to its mythical figurehead (the goat-headed Baphomet), the Satanic Temple also has a truly global community of loosely affiliated adherents, regular “services,” and “Seven Tenets,” in the style of the Decalogue or an early Christian creed.

Baphomet monument in front of the state capitol building in Little Rock, AR featured in HAIL SATAN?, a Magnolia Pictures release. (Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.)

The group knows, too, that “faith” without works is dead. The film’s narrative centers on the Temple’s political activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, where their attempt to raise an eight-foot statue of Baphomet near an extant Ten Commandments monument has spawned a massive controversy. This showdown with heartland conservatives and the Temple’s apparent competency are exhilarating for liberal viewers (this too gives the film its legs). Since premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in February, Hail Satan? has been called a “festival favorite” by Vice, “hilarious” by the New York Times, and “wickedly funny” by the Hollywood Reporter.

And the documentary does have plenty of funny moments. It opens with a Temple spokesperson in a long black cape and goat horns speaking on the Florida state capitol steps in support of a Republican bill allowing prayer in schools. Later, Temple members pick up roadside trash with pitchforks, and launch an after school educational program, much to the apoplectic chagrin of evangelical parents. The film also features the Temple’s efforts to give invocations at various city council meetings, an option open to them, at least theoretically, in the name of religious pluralism. When allowed, these invocations seem to go about as you’d expect. The comedy, at any rate, is in the Satanists’ self-awareness, and in how hungrily so many Christian fish are taking the bait. The Satanists know Satan isn’t real: the game is to expose hypocrisy by riling up America’s superstitious conservatives.

What is the humanist to make of all this? The star of Lane’s film (and the Temple’s founder), Lucien Greaves, appeared on the Humanist Hour podcast in early 2017 and spoke at the American Humanist Association’s annual conference later that year. There, he reported, to the attendees’ evident pleasure, on the Satanic Temple’s exploits, including some of the projects foregrounded in Lane’s film. Like the Baphomet statute, these efforts are responses to Christian indoctrination and monopoly over public spaces. Shoulder to shoulder against traditionally religious conservatives in America, the Satanist and the humanist are not just reluctant allies but enthusiastic comrades in rebellion against the Christian notion of a deity. In Paradise Lost, God is the authoritarian bully. And in the Temple’s version of the Genesis myth, Satan, lobbyist for freedom and access to knowledge, appears as the first human rights activist. Norwegian scholar Asbjørn Dyrendal has called Satanism “humanism with horns.”

My favorite moment in Lane’s film comes when Mason, a clean-shaven, bow-tied Satanist from Little Rock, Arkansas (yes, there is such a thing), explains that he’d been a “zesty little atheist” before getting involved with the Temple. His disdain for his former identity is winky but unmistakable. So is his enthusiasm at having found something more holistic than “God does not exist” as a rallying cry. And the comment is representative. Hail Satan? presents a community of people who have the secularist’s scorn for conservatism but consider themselves enthusiastically “religious.” It’s not totally surprising. When competing with more “positive” philosophical and political groups, atheism suffers from its own essential nature. We know what atheists are against. They tell us in the title. But what are they for? Into this space any number of thought systems might conceivably enter.

Full disclosure: Mason is my cousin (I saw the film with him at Sundance in a midnight showing the day after it premiered). I asked him directly where atheism now fits in his personal identity. His reply: “Skepticism is my nature, atheism is my belief, but Satanism is my religion.” However, is Satanism, upon further inspection, not subject to the same essential critique as atheism? In Hebrew, “Satan” is typically translated as “opponent” or “adversary.” What has Satanism ever been, at its core, except a reaction, a rejection, the denunciation of a status quo? Is its advantage, as a marketable costume on the cultural shelf, not purely optical?

Of course, it would have been difficult to get into all of this in Hail Satan?, but the film does, perhaps, deal a little too lightly with its subject. In happily tapping as mascot the traditional personification of evil, the Satanic Temple is (at least in a half-joking, theatrical way) throwing itself headlong into the Nietzschean game of reevaluating all values, including that long-time placeholder value for all that is good. If you believe Nietzsche, the Temple’s work is already done, at least philosophically, in the West (“God remains dead! And we have killed him!”). But if you really believe Nietzsche, this game is a bit more dangerous than we sometimes let on (“How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers?”).

There is no telling, at any rate, how many new movements, churches, cults, and identities might appear on the hyper-chaotic, post-Trump landscape in the coming decades, and no doubt the Satanists, as defenders of the Establishment Clause, will be fighting a worthy fight. Where is the humanist’s place in all of this? Perhaps we can, at least, better position ourselves in the Eden narrative. Adam and Eve, in our re-telling, refuse to be the created playthings of a capricious father figure, refuse to be kept in the dark about their own nature, or the nature of good and evil. We eat the fruit. Our eyes are open. The truth is hard to swallow, and the reality is, as Milton put it, no paradise, but we’re made nobler by facing it with our heads high, our shoulders back. For your scandalous suggestion, we thank you, Satan. But we can take it from here. From now on, we stand on our own feet and speak for ourselves.