No Small Thing: What Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Black Nones Have in Common

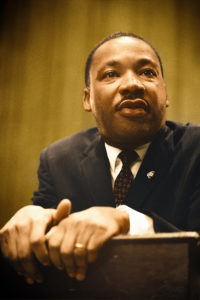

Photo by Unseen Histories on Unsplash

Photo by Unseen Histories on Unsplash It is not easy being an atheist in a world that is predominantly religious or even spiritual. And, there is not a day that goes by that I do not have to think about my atheism in relationship to the world and the people around me. Nevertheless, it is what it is. We live in a theistic world. As we remember the late, great Martin Luther King, Jr. I am reminded of a blog I wrote in 2015 entitled, “On the Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.: From an Atheist.” At the time, I had been “out” or openly atheist for about five years and I would often receive questions about my personal life from other atheists, such as, “Would you ever date a believer?” Now, after being public as an atheist for a little more than ten years, my position is the same as it was in 2015: I’m flexible. And my relationships with believers and non-believers, for work or play, have worked best when all parties involved are willing to respect differences and work together for a common purpose.

Unlike Dr. King, I am not a theist. In other words, I am not a believer in any alleged gods of any kind. While self-identifying as an atheist is not difficult for me, actually being an atheist is another story. I have seen my share of hate and discrimination from theists and others, including atheists. I cannot tell you how many times, for example, I have received rejection letters for employment when my would-be employer learned that I am an atheist. Likewise, it is still very difficult for some of my family and friends to accept this about me and that I have no problems identifying as a Black “none”, even when being a none–another word for someone who checks the “none” box when asked what religion they are affiliated with–has nothing to do with anything.

So, how do I do it? How do I maintain family, friendly, intimate, professional and other social relationships with those who believe in gods or supernatural things when I do not? Can’t I just build a world with my atheist, humanist, and agnostic friends and avoid them? Absolutely not, nor do I want to segregate myself on the basis of my non-belief. There is much more to being who I am than being an atheist. Furthermore, when has any group of people been able to just stick to themselves and reject meaningful interactions with others on planet Earth?

On my atheist journey, there came a time when I had to accept that–for now–the world that we live in is overwhelmingly theistic in orientation, but that does not mean that I have to be a theist, although I interact with theists most of the time in my personal and in my professional life. I realized that everybody cannot be just like me, think like me, talk like me, etc. And, if I am going to have any effect or any influence on others at all, I must try to find common ground or shared interests with others. I believe wholeheartedly that finding common ground is an essential part of our humanity, and, in so doing we can achieve civility, which is necessary to attain and maintain our democratic society.

So, here we are at the 36th anniversary of the Martin Luther Kr., Jr. national holiday, and as I reflect on my own journey to civility, I stop to ponder how the good Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lived such an exemplary life. Specifically, I am thinking about how he managed to be true to himself and his people when the white majority around him did everything in their power to keep him and other Black people from gaining the same rights, benefits and privileges as they had. One of the reasons I love talking about Dr. King in public circles is because he showed us that if we want to live in a civil society, one that makes room for everybody, then we have to be civil, and that means we must be willing to hear and see others as equals: we must respect their humanity. In the 1950’s and 60’s, this was no small thing.

Without a doubt, Dr. King was a man who was willing to challenge the white racist ideologies and philosophies of his time. This was very dangerous because Blacks were not treated or perceived as human equals to whites, and this idea was made manifest in just about every institution in the United States. During the mid-twentieth century, racist philosophies and socio-political ideas about blackness, vis-a-vis whiteness, were openly articulated in federal, local, and state policies and institutions, such as urban renewal, which was a federal housing policy that had a disparate impact upon urban Black communities. This approach to planning for urban development caused great social and spatial harm, and it had devastating consequences for Black people in particular. To be exact, it diminished their cultural and social power, and in some cases it sabotaged the social capital that my parents’ generation, Baby Boomers, had begun to build since the “Great Migration” out of the southern plantation economy. Psychologically and socially, it also enabled whites to believe that they were superior to Black people and their cultural and social representations, which were considered not as significant, or worthy of the same rights, attention, or even “love” given to white cultural representations. By “love” I simply mean recognition or acknowledgment.

One person who was deeply moved by Dr. King and his idea of the “beloved community,” was the world renowned Black feminist bell hooks, who recently died. It was hooks’ assertion that love is a combination of six ingredients: care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust. And this is something that we must remember. Perhaps you have seen the recent blockbuster movie King Richard produced in collaboration with tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams. It is a movie about the centrality of love in the Williams’ family, and the film highlights their parents’ love with the emphasis on their father Richard. There is a great line in the movie where the character Richard Williams, played by Will Smith, says to his daughters, “This world ain’t never had no respect for Richard Williams, but they gonna respect ya’ll.” In my opinion, it was one of the most powerful lines in the whole movie because we learn that not only was Richard Williams committed to his daughters’ success, he also loved them, and in loving them, he stood up for himself.

As an urban planning academician/scholar, I have learned that Black people and Black communities in the U.S. have not been valued or loved. In fact, the disregard, mistreatment, and abandonment of Black people and predominantly Black urban communities are subjects that I have explored in my scholarly work. Most recently in my brief but important electronic publication, Rebuilding Black Communities, With Love, I wrote about Ollie Gates, who was born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, and how he became the successful barbecue restaurant entrepreneur that he is today. In addition, on the cover of this publication, I intentionally featured the work of visual artist Harold D. Smith, Jr., who just retired from two decades of educating children and youth in Kansas City’s metropolitan area. The name of his piece is Duo. It makes me think of the struggles that indigenous peoples in and between the Americas and Africa have suffered as a result of what historians and sociologists have termed the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (TAST). Historians estimate that during the TAST approximately fifteen million people were kidnapped, raped, slaughtered, maimed, exploited for institutional profit and capital gain. Unfortunately, the horrible legacy of the TAST is still haunting us as a nation. Many urban Black communities, especially former Black ghettos in the U.S. are labeled and treated as loveless places, but when we look closely, we see that traditional or historical Black communities in the U.S. have deep reservoirs of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect and trust. In spite of how they are characterized by others, and despite the troubling realities that they face, there is love in Black communities.

I lived in Atlanta, Georgia at two different periods in my life, hence I have come to understand Dr. King as a man who stood against injustice and exclusion on personal and political terms. I have also read some of his books, so I know him as a great theologian who believed wholeheartedly that we as a people, American people, have the ability to live in civility. He dared to believe that with time we may even come to love each other despite the awful things that have happened in the past and in spite of deep racial divides that have plagued this nation for the last four centuries, including the ones we are witnessing today. Dr. King understood love at a very profound level and he was dedicated to the idea that every human being has worth no matter what they believe, or do not believe.

As he immersed himself in the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. King made it possible for the world to hear and see the human worth of Black people. Conversely, like his contemporary Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Dr. King posited that if someone goes out of their way to negate you or pretend that you do not exist, they are bound to make you suffer. Conversely, anytime you are able to look at others as equal to you in terms of human worth, then you are likely to give them your respect sooner or later. This is one of the greatest lessons that Dr. King gave us. And, he called upon the white majority of his time to respect Black people. By standing with them and for them, he loved his people and in loving them he loved himself. Of course, because he understood himself and others as people with basic human worth and rights, he believed that their freedom was also worth fighting for. The power of love can give us courage to do what is right.

It is very important for atheists and theists to understand the power that we have as humans to do and be good. This power is transformative. I have had the opportunity to talk about this before large groups of freethinkers. But, every now and then I will meet someone who says that they are an atheist, but they are not willing or able to stand up for themselves as atheist or humanist for one reason or another. Thus, for the time, being they remain silent. On the other hand, I have known many theists in life (in fact I used to be a theist as an ordained United Methodist clergywoman) who claim they serve a just and loving god, and they are not willing or perhaps able to stand up for themselves and for others. Theists remain silent in the face of injustice just like anybody else. But, here is what we must understand: if we are to be free in this society, we must find the strength and the courage to stand up for ourselves or for others when it is our turn to make this world better.

Recently, I had the opportunity to watch the docudrama Women of the Movement. The first episode told the story of Mamie Till-Mobley, the mother of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old adolescent who was tortured and murdered by white men in 1955. The title of the episode was “Let the World See,” which is what she said when she saw her son’s body after his brutal execution spurred by white rage and hatred for Black humanity, against Black boyhood or adolescence in particular. The reason we know the details of young Emmett’s ordeal is that his mother was willing to bring the humanity of her son to the public’s attention, even in his death. Till-Mobley insisted that the reality of Emmett’s death was worth something. The attention that she brought to the story of Emmett’s murder demonstrated that even in death our lives are valuable and powerful. In this troubled world that we live in, if we are going to know freedom we must be willing to stand up for ourselves and others when it is our turn. Like Till-Mobley and Dr. King, and the many others who were part of the Civil Rights Movement, we must love ourselves and others courageously, even when we are afraid or even if we may get hurt in the process through no fault of our own. If our society is to truly be a civil society, we are going to have to learn to be there for each other and to work together, or we will self-destruct.

I am always thankful for what Dr. King did to fight for the right to be seen and heard in a world that tried to negate him and his people. In standing up for his own community and people he made it possible for millions of others to enjoy freedoms in the United States that they may have never had without the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. King paid the ultimate price for others to live here and it is because he courageously articulated love in spite of hate that he taught others, including some whites, how to put aside their racist ideas, philosophies, and everyday practices. As an atheist, this is how I want to live: with love and civility, to the extent that has the potential to empower every human being, not just those who look and sound like me.

Dr. John Henrik Clarke, who died in 1998, is a respected Pan-African historian. Dr. Clarke has reminded us that the concept of an organized, civil society came out of the Nile River Valley, or what is now Africa and the Middle East. In the 1996 documentary Dr. John Henrik Clarke: A Great and Mighty Walk, he asserted that nearly all organized religions imposed religion as a framework to control Africans after Constantine began to invade and conquer North Africa. Religion went hand-in-hand with the slavery and the hijacking of African people from their native lands, and organized religion has been the weapon used by the world’s greatest empires ever since. Those who killed Emmett Till claimed to be god-fearing people and still today we do not have to look far to see theists on social media and elsewhere agreeing with the murder of Black women and men at traffic stops in broad daylight. There was a point in history when the church and organized religious groups would have been the only place where Blacks who felt threatened by racial violence and social unrest could find relief and safety, but that is not the case anymore.

In 2013, I wrote an article highlighting the activism of Black women atheists. This article, “Black Women, Atheist Activism and Human Rights” was published in an academic religious journal and it continues to inspire black writers and thinkers such as Dr. Jerry Rafiki Jenkins. His recent article, “Is Religiosity a Black Thing? Reading the Black None in Octavia E. Butler’s ‘The Book of Martha’” asks readers to think about the new role that Black nones have in fighting anti-blackness and racial violence. As I look at Black nones and the Black nontheist and Black humanist organizations, I am optimistic because it says that Black atheists have loved themselves in spite of the hatred that they get from friends, family, and even other atheists. And to stand up, they have had to be organized and civil. This too is no small thing.

On the 36th celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr., I am thinking of the brave stand that Black atheists have taken to assert their humanity in a world that is predominantly religious and culturally biased in favor of white representations of personhood and institutions. In doing so, they have given us all something to think about that is very humanist in orientation. In the film The Great and Mighty Walk, Dr. Clark concluded by saying that perhaps Black people would give the world its next humanity, but I want to propose instead that perhaps the world’s next humanity will come from Black atheists and those who will bring another dimension of civility and respect to our American society when it comes to our humanity. Both Dr. Clarke and Dr. King once said, in order to get someone off your back, stand straight up, and that is exactly what Black nones are doing. They have stood up for each other and they have created loving communities for those who do not believe. And, in a world such as ours, this is no small thing. For that, I believe Dr. King, whom Nina Simone called the “King of Love”, would be very, very proud.