The Reception of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species Historical British Periodical Perspectives (Part One)

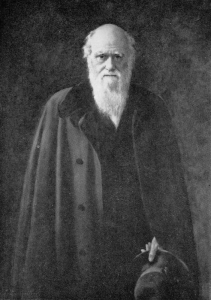

The publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 might aptly be described as a “revolution of evolution,” as it was an integral part of a larger debate. The scientific and religious communities of Darwin’s day had already been subjected to theories similar to Darwin’s natural selection (including those of his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Thomas Malthus, Charles Lyell, and Robert Chambers). Unlike his predecessors, Darwin’s theory seemed to have a greater impact, not least because his thesis wasn’t simply intelligent speculation but was a fully developed theory supported by a larger body of evidence.

Had Darwin’s theory actually produced a crisis of faith? John Hedley Brooke has asserted that after the publication of Darwin’s theories, people in nineteenth–century England found it harder to maintain faith in what they had once held to be dear. Could it be that they were led to dissociate themselves even further from something that they had never truly believed in the first place? The classic doctrines of Christianity were no longer secure behind the doors of an intellectual fortress, guarded by both science and religion; the unquestionable became susceptible to scientific enquiries, and the prescribed, time-honored answers seemed bleak and insufficient.

How did evangelical Christian communities in England receive Darwin’s theories at the time? In his meticulously researched work, Darwin and the General Reader (1990), Alvar Ellegård examined over one hundred English periodicals in an effort to ascertain how English society received Darwin, as reflected through these periodicals. His study led him to conclude that the commitments of each social/faith community can be discerned in relation to the objective considerations presented by Darwin. Though the uneducated majority tended to see that the issue at hand was one concerning the evolution of humanity from apes, the higher-educated and intellectual levels tended to view Darwin’s theories as an assault on traditional Christian doctrines (especially creation, the uniqueness of the soul/spirit of humanity, and “providence”). However, Ellegård points to the “theory’s patent contradiction of the biblical creation story which attracted the most attention when the theory’s religious consequences were discussed.”

Were Ellegård’s conclusions true for nonconformists in England? Though he surveyed a broad range of literature, Ellegård neglected to consult some periodicals that probably reflected the views of the average Evangelical church attendee. Once science had made strong assertions that threatened an impact on metaphysics and religion, the scientific advance would usually concede to religion as the authority. Since science and religion had been “reconciled” in the minds of some, the scientific community deemed it foolish to create a rift between the disciplines on account of “another theory,” given the persecutions of some scientists in the name of religion. However writers of the nineteenth century had made the rift wider and it would not be an incorrect assertion to claim that Darwin’s publications made the rift irreparable.

The concerns for the separation of religion and science became less of an issue as time progressed. For instance, an 1863 article in the British Quarterly Review commented on the “Epilogue of Affairs.” The author of this unsigned article sees that the issue behind Darwin’s publication centred on the relationship between revelation and the origin of humanity, instead of the connection between science and religion. When it comes to the relationship between “religion” and “science,” there is no discord; but the author encourages a separation between the disciplines of what the contributor refers to as “religion” and “quasi-science,” or ”modern science in the garb of science.”

A second issue in the midst of the debates around Darwin concerned the theology of “Providence” in the governing of the universe. This questioned natural theology’s assumptions of a world marked by peace, harmony, and order, instead of the struggle and competition for which Darwin had ascribed to it. The question of the universe’s governance was not who keeps things operating, but how. The works of the scientists immediately preceding Darwin (and Darwin himself) operated under the assumption that the laws of nature were logically fixed. The answer to their question of how a deity governed the universe increasingly became in the manner of scientific laws, not by meddling.

Whenever natural theology attempted to assert the sole divine creation of everything that exists in an ordered and harmonious fashion, it would continually encounter challenge from modern scientific investigations and theory. The reciprocal relationship between science and theology meant that science could have a direct impact upon the conclusions of natural theology. Given the course of events in the nineteenth century, natural theology was not destroyed by the natural sciences, but rather “eased out” of scientific culture as irrelevant. In time it was no longer accepted that the design, purpose, and sustenance of a deity were vital to hold everything in life together. An article submitted to The Baptist Magazine in 1869 asserts that the act of creation essentially began a lengthy (and ongoing) process of growth, in which larger results are brought about by the “building-up of smaller ones.”This illustrates that the question was more about how our world came to be rather than who created all that is.